Kaitlyn Greenidge and her sisters achieved success in their respective fields. In her historical novel, “Libertie,” she focuses on a Black woman who doesn’t yearn to be the first or only one of anything.

A review by Alexandra Alter for The New York Times.

Libertie, the rebellious heroine of Kaitlyn Greenidge’s new novel, comes from an extraordinary family, but longs to be ordinary.

As a young Black woman growing up in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie is expected to follow in the footsteps of her trailblazing mother, a doctor who founded a women’s clinic. Instead, she flunks out of college and marries her first suitor, hoping to lead a tranquil domestic life.

Greenidge based her book partly on Susan Smith McKinney Steward, who in the 1870s was the first Black woman to become a doctor in New York State. As she researched the family, she found herself drawn to the doctor’s wayward daughter, Anna. She became the model for Libertie, the kind of historical figure who is rarely celebrated: someone who simply wants to survive and thrive, not to be the first or the only one of anything.

“So much of Black history is focused on exceptional people,” Greenidge said in a video interview earlier this month. “Part of what I wanted to explore is, what’s the emotional and psychological toll of being an exception, of being exceptional, and also, what about the people who just want to have a regular life and find freedom and achievement in being able to live in peace with their family — which is what Libertie wants?”

Greenidge comes from a family of exceptional women herself. Her sister Kerri Greenidge is a historian who specializes in African-American and African diasporic histories, literature, and politics. Her other sister, Kirsten Greenidge, is an Obie Award-winning playwright and a theater professor at Boston University. Growing up in mostly white, wealthy suburbs around Boston, raised by a single mother who struggled to support the family on her social worker’s salary, all three felt pressure to succeed in rarefied fields where they often felt like exceptions.

“That idea of being the first and the only was a big piece of our experience,” Greenidge said.

Since the start of the pandemic, she has been quarantining with her mother and sisters in a woodsy suburb in central Massachusetts. Occasionally, when their interests and schedules have aligned, they’ve collaborated on creative ventures, including a podcast and a history project. They are engaged in ongoing conversations about their writing, though they draw the line at reading and editing drafts of one another’s work.

“My sisters and I have always been extremely close and we are each other’s greatest fans, but we have always been our own people,” Kerri said.

All three have risen to prominence in their respective genres, and they have produced enough award-winning literature to fill a bookstore display. Kirsten, the oldest, has written and staged around a dozen plays, works that often explore the lives of Black women and families in the Northeast. Kerri — who teaches at Tufts University, where she is the Mellon assistant professor in the Department of Studies in Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora — has published groundbreaking books about Boston abolitionists and the Black activist William Trotter. Kaitlyn, the youngest at 39, was hailed for her 2016 debut, “We Love You, Charlie Freeman,” a novel about a Black family taking part in a morally fraught experiment by adopting a chimpanzee and teaching him sign language. (She’s also a contributing Op-Ed writer for The New York Times.)

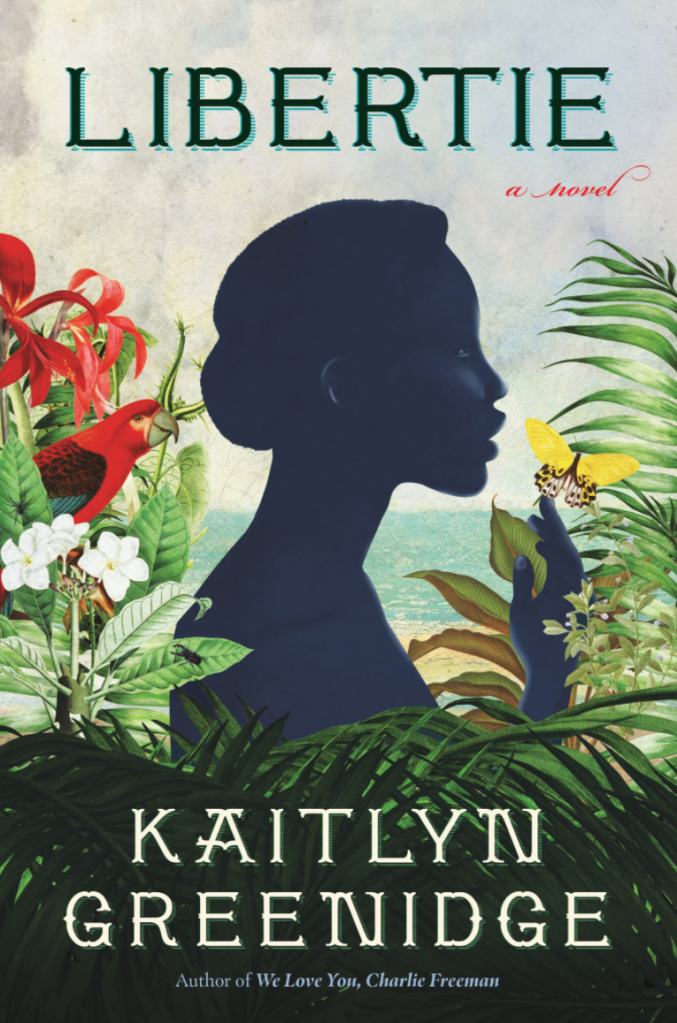

With “Libertie,” which Algonquin is publishing next week, Greenidge is making a stylistic leap with an intricately researched and lushly imagined coming-of-age story set in 19th-century Brooklyn and Jacmel, Haiti. The novel has drawn praise from writers like Jacqueline Woodson, Mira Jacob and Garth Greenwell, who wrote in a blurb that Greenidge “adds an indelible new sound to American literature, and confirms her status as one of our most gifted young writers.”

“There’s a really powerful lyricism that feels new in this voice,” said the novelist Alexander Chee, who was Greenidge’s writing professor at Wesleyan.

For Greenidge, writing about Black women living through social upheaval felt like a return to her long-running obsessions: questions about whose stories get told as part of American history, how trauma is passed down across generations, what it means to be free of the past.

“I’ve always been interested in the histories of things that are lesser known,” she said. “If you come from a marginalized community, one of the ways you are marginalized is people telling you that you don’t have any history, or that your history is somehow diminished, or it’s very flat, or it’s not somehow as rich as the dominant history.”

Greenidge and her sisters developed a reverence for storytelling and history early on, when their parents and grandparents would tell stories about their ancestors and what life was like during the civil rights movement. Their grandparents were among the first Black people to move to Arlington, Mass., and recruited a white friend to pose as the home buyer, a scenario that Kirsten drew on in her play “The Luck of the Irish.”

“That connected us to a historical narrative and possibly led to all of us studying history in our ways,” Kirsten said.

Their mother, Ariel, encouraged them to find creative ways to entertain themselves. So they wrote stories, played instruments and staged elaborate plays that Kirsten wrote. They recorded make-believe radio shows on a cassette player, belting out the soundtracks to “Grease,” and other musicals.

Kaitlyn was a precocious reader and absorbed books far above her grade level because her sisters would read aloud from whatever they were into at the time, regardless of whether the plots were appropriate. “We scared the heck out of that poor kid,” Kirsten said.

Outside of their boisterous, creative home life, the sisters were keenly aware of race and class and how it defined them in the largely white prep schools they attended. Those issues became more pronounced after their mother and father, a lawyer, divorced, when Kaitlyn was 7. Suddenly, they went from being upper middle class to sliding below the poverty line and relying on public assistance.

“That fracture was really formative for me,” she said. “It made me hyper aware of inequality and the doublespeak that goes on in America around the American dream and American exceptionalism, because that was proven to me not to be true.”

The change in the family’s economic status also increased the pressure the sisters felt to excel. “As young women of color in America, that was made clear to us from very early on, definitely feeling the onus of, How are you going to put your education to use?” Kirsten said.

After Kaitlyn Greenidge graduated from Wesleyan, she worked as a park ranger, phone banker and researcher at historical sites, and designed a vocabulary app for an education technology company. She kept writing, publishing essays and articles and, eventually, her debut novel, which won her a Whiting Award in fiction.

She got the idea for “Libertie” a decade ago, when she was working at the Weeksville Heritage Center, a museum dedicated to a free Black community that was founded in Brooklyn in 1838. Greenidge was collecting stories from people whose ancestors had lived there, and tracked down a woman named Ellen Holly, who was the first Black actress to have a lead, recurring role on daytime TV, in “One Life to Live.” Holly spoke about her great-grandmother Susan Smith McKinney Steward, whose daughter Anna married a son of the Episcopal archbishop of Haiti and moved with him to Port-au-Prince, but came to regret it.

Greenidge filed the family’s saga away in her mind, thinking she had the premise for a novel. When she got a writing fellowship, she was able to quit her side jobs and immerse herself in the research the novel required. She read old newspapers, political tracts, sermons, memoirs, hymns and census records. Occasionally, she turned to Kerri — she affectionately calls her older sister a “history nerd” — for advice. “She’s a human Wikipedia,” she said. “How could you not?”

The resulting story feels both epic and intimate. As she reimagined the lives of the doctor and her daughter, Greenidge wove in other historical figures and events. In one horrific scene, Libertie and her mother tend to Black families who fled Manhattan during the New York City draft riots. In the novel’s opening chapter, Libertie sees her mother revive a man who arrives at their home sealed in a coffin, brought by a woman who works on the Underground Railroad. Greenidge based the woman on Henrietta Duterte, a Black abolitionist in Philadelphia who used her funeral home to help people escape.

Greenidge also drew on her own family history, and her experience of being a new mother. Her daughter, Mavis, was born days after she finished a second draft of the book, and is now 18 months old. She finished revisions while living in a multigenerational household with her own mother and sisters.

“Mother-daughter relationships are like the central relationships in my life,” she said. “One of the things I was interested in was motherhood as this place of self-creation.”

She took inspiration from Toni Morrison, who once described motherhood as “the most liberating thing that ever happened to me.”

That idea, of motherhood as a catalyst for self-discovery, became a refrain toward the end of the novel, when Libertie reads a letter from her mother. “I cannot think of a greater freedom than raising you,” it says.