Jakarta, Indonesia—The central business district of Indonesia’s 11 million-person capital has the social contrast found in many other developing world megacities. Modern skyscrapers accommodate Indonesia’s elite, while shabby informal villages spread from the base of such buildings. I wanted to experience this latter, more common, style so one morning my translator Julya and I walked a few minutes from my upscale French hotel chain across a dirty canal and into a village.

The standardized First World planning aesthetic of square buildings and engineered roadways quickly yielded to clustered huts organized along a twisty network of alleys. This village style is common in the Third World, a bastion of organic, market-oriented development that often withstands the modernization plans of city officials, even in central areas. It bears a striking resemblance to a popular concept in the Western urban planning world: the “superblock.”

In superblocks, wide roads and streets are spaced far apart rather than allocated frequently on a grid pattern. The area in between, too condensed to accommodate cars, is reserved for pedestrians, motorbikes, buildings, and courtyards, with alleyways connecting it all.

Such blocks were the historical default before cities were planned for automobiles and before machines made clearing rights of way much easier. Paths would extend along routes that were topographically easy and would be cleared just wide enough for needed pass-throughs.

European villages with their hilly outdoor staircases fit the superblock stereotype, but the style has even deeper roots in Asia, with the oldest known example in China. In their contribution to the book Governing Cities: Asia’s Urban Transformation, scholars Daixin Dai and George R. Frantz describe the ones planned in 1036 B.C. for the ancient city of Chengzhou. The pattern persisted through the millennia; 1400s Beijing, according to urbanNext, consisted of “blocks of houses on 150-meter hutong nested in 1,000-meter superblocks,” themselves found in larger structures called “megablocks.”

Superblocks were common in the colonial and industrial-era U.S., with Philadelphia, for example, growing into a maze of tight alleyways for horse carriages. Savannah, Georgia, was planned for superblocks—still partially intact today—and there are still scattered examples throughout the Northeast and Midwest.

Modern planners increasingly recognize the benefits of superblocks and want to bring them back. Cutting off large residential segments of the city to cars reduces traffic deaths, air pollution, and other negative externalities. The idea has been proposed in Los Angeles, where the City Council hopes to implement a pilot superblock in the city center, and in Seattle, where one is proposed for the Capitol Hill neighborhood.

Urban planners tend to be progressives, and superblock promoters think their idea will be achieved through government planning. The most successful First World superblock retrofit was pushed through that way, in Barcelona. There, the government prohibited automobile traffic through several thoroughfares in the 2010s, allowing pedestrians to move through freely; the authorities hope to create 500 such blocks. Beyond just alleys, a number of blocks have shops, courtyards, and parks.

The effort caused car storage in one Barcelona neighborhood to fall 82 percent. The change has plenty of fans: The World Health Organization reports that in one converted district, residents experienced “a perceived gain in well-being, tranquility and quality of sleep.” And it was clearly a government project. As David Roberts wrote in Vox almost five years ago, Barcelona “has always been an intentional city, closely conceived and constructed by central planners.” Unsurprisingly, it was planners, in turn, who undid the city’s grid and instilled superblocks.

But across the developing world, the opposite is true. In Africa, Asia, and Latin America, superblocks remain the de facto market-driven development pattern, for much the same reasons they were in the ancient world. Most of the population doesn’t own cars and is not in an economic position to afford more space. So they maximize the space they have, causing superblock shantytowns to pop up on hillsides, farmland, or even infill urban areas that are being illegally “invaded.” The poorer the area, the more devoid it will be of setback requirements, parking minimums, and similar regulations—and the likelier it will be to yield the superblock vernacular.

***

We got a sense of the economic reasons why when walking through the Jakarta village, called Kebon Jahe. This is one of central Jakarta’s many urban villages—a neighborhood format known to locals as perkampungan. Kebon Jahe literally is a superblock, in that the entire boundary is one big block of a dozen or so square acres, flanked by big arterial roads but with no significant through roads.

We entered the village wanting to learn how it got planned (or unplanned) to look this way. Julya, a native to the Jakarta area, knew we must first talk to the neighborhood chief.

After veering down one alley and asking around, we were taken down an even smaller alley and introduced to Budi Aprianto. A middle-aged man, he is one of 15 village chiefs, all democratically elected by the block’s roughly 1,500 residents.

Kebon Jahe, he explained, was colonized in the 1700s by the Dutch, who built a cemetery there. When Indonesians got back control of the land during the 1940s revolution, the area was converted into farmland and a livestock market. The buildings that exist now began rising in the 1970s, to accompany population demands in central Jakarta. The village has not grown through the efforts of a master developer. A collection of families, many of them in the area for generations, had erected their own homes.

How, I asked, did a sophisticated alley network get built in such a decentralized growth system? After I paid a small bribe, he agreed to show me around.

The network, he explained, is as coordinated as it looks, forming a U shape that lets residents access the whole village. But there are three right-of-way categories.

The first consists of the relatively wide roads that form the entry of Kebon Jahe before hitting up against alleys. These were built by the government, allow cars to park (haphazardly), and have formal retail, such as the popular Alfamart chain.

The second, and primary, form of right of way is the alleys. They’re 6 feet to 12 feet wide, meaning they can only handle pedestrians and motorbikes, and they accommodate most of the retail, with merchants setting up stores along or even into the alley. The government paves them and manages them for safety and clearance, but they follow a market logic. They began as private clearances for farmers who were seeking the easiest transport path. Development grew along them, and only later did the government take over. This is why they zigzag along land curves rather than fitting the straight lines common in a grid.

Third are the extremely narrow alleys that veer off these main ones. These are still private. Any given acre in Kebon Jahe has hundreds of small houses so scrunched together it’s hard to tell them apart. Most homes don’t front the street but, in a pattern atypical in even America’s densest cities, go deep into the lot—meaning almost every last square foot of land is covered.

The only parts not covered are the alleys, which allow inside-outside access for these further-back houses. The alleys are also places for hanging birdcages, drying laundry, and running small commercial stands. They’re created through negotiation between homeowners, all of whom benefit from the access. But they’re extremely narrow—I had to turn sideways while walking through some—and that just boils down to economics.

“Jakarta is a very crowded city,” Aprianto explained through my translator. “People use every bit of space they can for themselves.”

Some of the extremely narrow alleys actually began as the wider formal public ones. But when adjacent homeowners want to expand their dwellings, they build additions into the alley, unintentionally similar to the invasive favela-style growth seen in Brazil. These households leave just enough alley space that they themselves can get out.

While building onto public alleys is illegal, enforcement is loose, given that Kebon Jahe is a mostly self-governing slum. (Aprianto is an elected leader, but he is not a government official.) In the rare cases when city inspectors appear, residents just pay them off.

Before visiting Kebon Jahe, Julya and I explored some superblocks in Tangerang, the working-class Jakarta suburb where she grew up. Many more exist there—unsurprisingly, given that it’s an industrial city where factory workers need places to live. Tangerang superblocks are often centered around small mosques (Indonesia is the country with the world’s largest Islamic population) or around dirty canals that nonetheless meet certain economic needs.

The same order can be found across the Global South: Large factories are built on city outskirts and quickly get surrounded by informal slums, virtually all of which adopt some variation of the superblock layout. Again, this is not because people there share the ideals of Western planners. Nor do these superblocks have the bells and whistles of the Spanish ones. It’s simply the most logical layout in societies defined by economic and spatial scarcity.

Superblocks are more vulnerable in central areas, thanks to pressure to wipe them out and build to higher-end uses. That is not usually a market process. As our Kebon Jahe tour was ending, we passed the more formal area at the village exit, which had a wider alley and larger buildings.

“By next year, all of Kebon Jahe might look like this,” Aprianto said.

The city has already started harassing the village’s street merchants, and it’s planning a program to raze Kebon Jahe homes and replace them with towers. Residents will receive payments from the government that, while large to them, won’t be enough to buy replacement units in central Jakarta. Instead, they must find comparably priced units further out, meaning they’re effectively being displaced through eminent domain. Such slum clearance is common across the Global South, as it once was in the United States.

It might surprise America’s professional planners to hear it, but governments don’t usually create superblocks—they destroy them.

The post How Third-World Countries Build Walkable Cities Without Central Planning appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

At the end of 2021, John Morse hoped he could breathe a well-earned sigh of relief.

It had been two tough years. The pandemic had pushed Celebrations—the wedding venue he and his wife Laurie had owned and operated for two decades in rural Caroline, New York—to the brink of ruin. But with public health restrictions disappearing and with brides and grooms planning nuptials once again, the Morses were ready to resume business.

“We have a beautiful piece of property. But we’re not a castle on the lake with marble columns,” he says. “There [are] wedding venues out there that are booked three, four years in advance. That’s not us. We’ve always had to work hard for the business that we have.”

Morse hoped that 2022 would be a normal, relatively drama-free year. That hope was dashed in November, when a little blue postcard arrived in the mail. Caroline’s zoning commission was inviting him to an informational meeting on its draft zoning code.

The card took Morse by surprise. He wasn’t aware that the town had a zoning commission. Caroline, after all, had no zoning code.

That makes it an extreme outlier in the United States.

Almost every other community in the country has a code that assigns each property in town to a zoning district and then lays out a long list of rules describing the kinds of buildings and activities allowed (or not allowed) there.

Proponents see zoning as an uncontroversial means of keeping glue factories away from homes, keeping strip clubs away from schools, and generally protecting things everyone likes: open space, property values, the environment, and more.

But ever-mounting home prices and a growing number of stifled small business owners are prompting a critical rethink of just how useful or necessary this mess of red tape and regulation really is.

Once an afterthought, zoning has become the hot-button issue in city halls and state capitals across the country. The debate is increasingly about how best to liberalize the rules that are on the books.

But in Caroline, that national debate is now playing out in reverse.

This was ostensibly a dispute about traffic, environmental protection, sightlines, and neighborhood character. It quickly became a conflict over class and class aesthetics. The pro-zoning residents were, in many cases, current and former employees of nearby Cornell University. They had a very specific vision of what the town should look like, and that vision often clashed with what people were doing, or might one day do, with their property. If Caroline’s special character needed legal protections or legal limits on landowners’ property rights, they reasoned, then so be it.

But for Morse, the freedom to do what he wants on his own land is part of what makes Caroline special. Far from protecting the town’s character, zoning is a threat to it. He’s not the only one to feel this way.

After receiving the blue postcard, he started to call around to other businesses in the area to see what they’d heard and what they were thinking. “Most didn’t know about it; none of them wanted it,” says Morse. “People are going to lose their freedoms on their properties.”

Within a few weeks, he’d helped organize a coalition of hundreds of Caroline farmers, business owners, builders, and ordinary residents who saw the proposed code as a threat to their plans and freedoms.

Their opposition would turn what could have been a dry planning exercise into a high-stakes, often highly emotional fight. On road signs and at frigid winter protests, anti-zoners have been repeating a motto: “Zoning kills dreams.”

Saying No

The debate that has consumed Caroline was sparked by a dispute over a single property.

Ken Miller, a hay farmer and Marine veteran, owns about 30 acres of land in town. In 2019, real estate firm Franklin Land Associates approached him and asked if he’d be willing to sell some of his acreage for a potential commercial development.”

Things were pretty tight when they came to us,” says Miller. The always-precarious farming business was getting harder and harder for the septuagenarian to manage, both financially and physically. He’d recently had knee surgery and had been working at a nearby hardware store to help make ends meet.

Such situations are common in the area. Particularly in the dairy business, agricultural consolidation has made most small, locally owned farms unprofitable. One way these farmers manage to stay in business is by selling off some of their marginal acreage for development. That gives them enough money to pay their property taxes while still keeping their prime farmland under plow.

That was Miller’s plan. If Franklin was willing to pay commercial real estate prices for the land, he’d even be able to retire with a bit of a nest egg. He and his wife could afford to take long-deferred trips together.

The trouble for Miller was that the party ultimately interested in his land was a controversial one: Dollar General.

The low-cost general store is a fixture in poorer rural areas, where it’s often the only food store around. For the people who shop there, it can be an essential source of daily necessities. Having one in Caroline would save people the need to drive farther to shop at a store that was more expensive.

Critics say Dollar General drives out local competitors, sells unhealthy food, pays low wages, and generally diminishes an area’s character. These criticisms, particularly the last one, resonated with one set of Caroline residents.

For most of its 200-year history, Caroline has been a small agricultural town. But a large segment of its 3,368 residents consists of current or former faculty and staff at Cornell University, located just up the road in nearby Ithaca.

Many of these residents like Caroline precisely because it doesn’t have lots of chain stores and commercial strips. They saw in Dollar General a harbinger of the suburban sprawl they had moved to town to avoid—and they were determined to stop it.

In February 2020, Franklin, under contract to buy Miller’s land, submitted the necessary documents to the town government to get approval for a Dollar General.

While Caroline doesn’t have a zoning code, it does have a comprehensive plan—sort of a vision document for the town—that calls for protecting local businesses and farmland. It also has a review board that is tasked with ensuring larger developments conform to that comprehensive plan.

On the board at the time of Franklin’s application was Ellen Harrison, an environmental scientist and former director of a waste management institute at Cornell. She said Franklin’s proposal for a large commercial development presented a major dilemma. Dollar General wasn’t a local business and it would be paving over existing farmland.

“I could not affirm that it was consistent with the comprehensive plan….I couldn’t say yes,” she says. “On the other hand, I couldn’t say no. Without zoning, there is no way to say no.”

Harrison and like-minded residents felt they had to act fast if they were going to keep the store and others like it out of town.

The March 2020 meeting where the review board would consider the Dollar General proposal was canceled because of COVID-19. By April, the town board was drafting a development moratorium that would halt approvals of any commercial projects for 180 days. In June, the town board approved the moratorium.

Town Supervisor Mark Witmer, an ornithologist and occasional Cornell lecturer, told the local Tompkins Weekly the moratorium wasn’t about the Dollar General per se. It was, he said, about giving the town breathing room to finish a comprehensive plan update that was underway.

Still, an undeniable effect of the moratorium was that the Dollar General project was effectively dead.

Franklin Land Associates felt its project was being singled out. An April 2020 letter from the firm’s lawyers to Witmer called the moratorium “stupefying” and potentially illegal.

It was a big loss for Miller too, who had to forfeit the $150,000 he would have gotten from selling his land. The fight took a heavy toll on his and his wife’s relationship with some of their neighbors, several of whom had signed a petition opposing the Dollar General.

“We were hurt, and we were hurt financially,” he says. “That’s a lot of money.”

The moratorium also presented a problem for the town’s growth critics. The building freeze was supposed to last only 180 days while a new comprehensive plan was finalized. But it wasn’t as if that plan was going to stop future Dollar Generals. For that, the town needed zoning.

So in December, the town board extended the moratorium for another 180 days. It’s since been extended three more times. It’s not set to lapse until February 2024. Meanwhile, in January 2021, the updated comprehensive plan was finally adopted. And the month after that, the town board voted to create a commission to get to work drafting a zoning code.

Drafting Errors

Over the next two years, the Caroline zoning commission’s draft code would go through lots of tweaks and revisions. But the substance remained largely unchanged. The plan was to separate the town into three types of districts.

Caroline’s pockets of existing development were to be zoned as “hamlets” where housing, home businesses, and limited commercial uses were allowed. There would also be a “focused commercial” district where formula retail (a.k.a. chain stores), storage facilities, and other larger businesses would be permitted. Then the vast majority of the town’s land was grouped into a “rural/agriculture” district where both residential development and nonfarm businesses were strictly curtailed.

For the people on the zoning commission, this represented a well-crafted balance between protecting the town from rampant development and letting people use their land as they always had.”

We are trying to craft a zoning plan that is appropriate for Caroline that puts some important safeguards in place but does not put undue burdens on land owners,” says Bill Podulka, a retired physicist at Cornell and member of Caroline’s zoning commission.

In relative terms, the 137-page draft code is a lot simpler than what you might find in a major city, where the zoning code runs for thousands of pages and creates dozens of special districts.

Caroline’s draft code was nevertheless 137 pages of regulations that didn’t exist before.”

When you look at the restrictions that come into play, there’s a whole giant table of what you’re allowed to have or [not] have,” Morse says. “You can have this kind of business because we like it, you can’t have this kind of business because we don’t like it.”

One thing Morse had always planned for his business was building rental cabins on a vacant field he owned next to his venue, where wedding parties could stay after the ceremony. But “campgrounds” are flatly prohibited in the focused commercial area that would cover his property.

As Morse got out the word about the zoning code, more people realized their own plans for their land would be banned or subject to a lot more rules going forward.

That included Hannah Crispell Wylie, whose family had maintained a 1,000-acre farm in Caroline for the past 175 years. One idea her family had to prop up their always-precarious agriculture business would be setting aside some unfarmable land for a small campground or R.V. park.

Without zoning, Wylie would have been within her rights to just go ahead and do that. Under the draft zoning code, she’d have to get a special use permit. And that’s no small order.

Getting that permit would require Wylie to file applications with the town’s review board, which would hold a public hearing, where neighbors would have an opportunity to complain about the project. After a hearing, the board would have months to decide whether Wylie’s campground would disturb the character of the neighborhood, be consistent with the comprehensive plan, damage the environment, impact adjacent property owners, or strain public services. At the end of that process, the board could put a lot of expensive conditions on the proposed campground to mitigate its impact on that long list of things. Or the board could just say no.

Podulka insists the review process isn’t intended to be a roadblock.

“Review doesn’t mean you can’t do it, it just means a meeting, or two, or three, yes,” he says. “You may or may not have to make some adjustments to meet some of the desires of the rest of the community.”

Wylie says that the time and expense of the review process could be enough to deter her from even applying for a permit in the first place. She could end up spending a few hundred (or a few thousand) dollars and several months getting permission to start a business that might not work.

Without the ability to easily and cheaply experiment with new ideas, her family’s continued operation and ownership of their farmland was imperiled.

“We have something so beautiful to take care of and we’d like to keep it,” she says.

Planning boards and commissions that enforce zoning laws unsurprisingly often become dominated by people who have pretty restrictive views of what people should be allowed to do on their properties.

Caroline already got a taste of that when the town stopped the Dollar General project.

The town’s anti-zoning activists like to point out that the store would have been built just a few hundred yards from a review board member’s house, which they say is evidence of how personalized these things can become.

“You have to ask permission from people you don’t like and who don’t like you,” says Bruno Schickel, a local developer and member of Caroline’s anti-zoning coalition.

Even when personal feelings or self-interest don’t creep into the zoning process, unintended consequences will still abound, Schickel argues.

Take the village of Boiceville, a Schickel development of 140 closely spaced, fairytale-like tiny homes whose design was inspired by the children’s book Miss Rumphius. The clustered development of the cottages means Boiceville shelters about 10 percent of Caroline’s population on just 40 acres. The economical use of land and lack of entitlement costs also keeps Boiceville more affordable than it otherwise would be.

In many ways, Boiceville is in keeping with the spirit of much of Caroline’s draft zoning code, which calls for the preservation of open space and affordable housing. But the village’s design would be prohibited by the letter of the code, which limits residential development in rural areas to an average of one dwelling unit per three acres. If Boiceville were built today, it would have to consume 10 times as much land. The more land a development requires, the more it ends up costing.

As 2022 wore on, the zoning commission continued its work of refining its draft code. Meanwhile, in the town, anti-zoning residents spun up a guerrilla activist campaign against the commission’s work.

Signs went up: “Grandma Hates Zoning,” “Caroline Forever Unzoned,” and so on. Residents held protests at the town hall where farmers brought their horses painted with similar anti-zoning slogans.

The fight got pretty personal pretty quickly.

When Harrison put up a sign supporting zoning in her yard, she says, someone defecated on it. The Ithaca Voice reported that the chair of the zoning commission received an emailed death threat.

On the flip side, anti-zoning residents argued that the zoning commissioners and town board members were being openly contemptuous of their concerns and flatly unwilling to listen.

The town board, they noted, stuck to Zoom meetings in a town where many residents didn’t have high-speed internet.

During one meeting where anti-zoning residents invoked their families’ long history in the town, a town board member said they were sick of hearing about people’s heritage. In response, Wylie put up a road sign saying, “Piss on zoning, not our heritage.”

When anti-zoning people raised general concerns about zoning, pro-zoners told them they needed to be specific about their complaints. When they raised specific concerns, the response was often that the code was only a draft and the offending provisions might not end up being included. Anti-zoning activists could be forgiven for feeling gaslit.

To an extent, the pro- and anti-zoning camps could be grafted onto preexisting political differences. Supporters of the draft code skewed liberal, while the town’s conservatives were more likely to oppose it.

But the class dynamic of the zoning fight scrambled these neat partisan lines. The anti-zoning coalition included folks like Morse, whose wedding venue was hosting a fundraiser for a crisis pregnancy center the week this reporter was there. It also included Tonya VanCamp, a nonprofit worker, whose home sported a gay pride flag and a “Black Lives Matter” sign. Both were united by a fear of what zoning would prevent them from doing with their single biggest asset: their land.

On the flip side, people who might have made common cause with the anti-zoners in different circumstances decided to stay on the sidelines. Sara Bronin, a Cornell professor who founded the zoning reform group Desegregate Connecticut, said in an email she was approached about getting involved in Caroline’s debate but declined.

The town’s debate had less to do with the specifics of a zoning code, and more to do with “rural stubbornness,” she wrote.

Yet the hypothetical concerns they were raising with zoning were also critiques that a growing number of academics, policy wonks, and activists were making about the very real effects of zoning in communities across the country. Caroline’s seemingly parochial fight brought the town into a very national conversation.

Straitjackets

Caroline’s pro-zoning officials and residents frequently complained their critics were exaggerating how burdensome the draft code was, when they even bothered to raise specific complaints at all.

The anti-zoners’ objections all seem reasonable enough to M. Nolan Gray.

Gray doesn’t live in Caroline. He lives in Los Angeles, where he works as research director for the housing advocacy group California YIMBY. (He’s also an occasional contributor to Reason.) This is one of the organizations to grow out of the original “yes in my backyard” (YIMBY) movement of San Francisco Bay Area residents who got fed up with spending more and more of their money on increasingly scarce housing. Beginning in the mid-2010s, they launched a crusade against the zoning restrictions they blamed for the Golden State’s astronomical rents and home prices.

YIMBYs face an uphill battle in most urban areas, where long and extensive zoning codes ban apartment buildings across most of the city. The movement has nevertheless won over a lot of converts in these expensive cities with a message that housing would be cheaper if it were legal to build more of it.

Policy makers across the country are increasingly talking like they agree with that idea, and even adopting policy reforms designed to allow for more building.

Three states, including California, have passed laws legalizing at least duplexes statewide. A handful of other states will probably follow suit this year. President Joe Biden’s White House has called out restrictive zoning laws in strong terms. (Biden’s actual policies don’t do much to address the problem.)

Gray himself wrote a book arguing that zoning should be not just liberalized but abolished. That’s a radical position even within the YIMBY movement. It can seem hopelessly utopian when you consider how expansive and restrictive the average city’s zoning code already is.

But the message resonated in Caroline, where residents don’t live under zoning now and many want to keep it that way.

After discovering Gray’s book, some of the town’s anti-zoning activists reached out and asked if he’d take a look at Caroline’s proposed draft code. What Gray saw was a restrictive mess that would bring to Caroline problems that zoning had created everywhere else.

“It’s untethered from any actual impact that’s facing Caroline,” he says.

The code’s requirements for site plan review and special use permits would be incredibly burdensome for the low-impact small businesses that would likely open in the town. The minimum lot sizes and density restrictions would drive up housing costs. Even if a restriction wasn’t in the code now, it could easily be added later.

“Once these codes are adopted, it’s a one-way ratchet that only gets stricter, that only gets more exclusionary, that puts jurisdictions in a tighter and tighter straitjacket,” says Gray.

At the invitation of Caroline’s anti-zoners, Gray went out to the town in November 2022 to make the case for why adopting zoning would be a mistake.

The night before the 2022 midterm elections, he gave a presentation to a packed community center where he laid out the general case against zoning and what it would do to Caroline specifically.

He pulled up a map of the town dotted with red-colored parcels. Members of the audience gasped when he explained that each red parcel was a property that would be made nonconforming by the draft code. That meant even minor changes to the property would have to go through site plan review and more substantial expansions or changes of use might be banned entirely.

Next, he brought up pictures of businesses and buildings in town, and explained how the draft zoning code would make their various features illegal too.

“So much of what’s in this code is stuff other cities are trying to get rid of,” said Gray during his talk. Caroline need not make the same mistakes.

Gray’s talk was meant to be a calm presentation of zoning’s problems. It quickly became a venting session for the assembled crowd of mostly anti-zoning residents.

The first question in a Q&A session was from one man who asked Gray what the penalties would be for “civil disobedience” with the zoning code. Another woman asked whether you could keep zoning code officers off your property if they didn’t have a warrant.

When Katherine Goldberg, a town board member considered to be a moderate on the zoning code, stood up to urge people to trust the process, many responded with angry shouts.

Caroline’s anti-zoning activists had planned to have Gray speak during public comment at the town board meeting a few days later. That meeting was abruptly canceled just before his visit. The explanation was that Witmer, the pro-zoning town supervisor, was taking a long-planned trip to Hawaii but had neglected to inform the town clerk ahead of time.

For anti-zoning residents, it was just one more piece of evidence their government was totally uninterested in hearing their concerns.

On the night of the now-canceled board meeting, they braved the freezing cold weather to make their case heard in front of the empty town hall.

Morse got in front of the crowd and hoisted a thick petition of 1,200 signatures demanding that any vote on a zoning code be delayed until after Caroline’s 2023 municipal elections. Zoning was not what people wanted, he said.

Next came Schickel, who earned cheers when he informed the crowd that two anti-zoning town board candidates had won their election in the nearby town of Hector, which was having a similar fight over whether to adopt a zoning code.

The crowd periodically broke out in chants of “no zoning.” Some people in the back cracked open beers. Across the street, a large trailer bore a huge display of lights and illuminated letters reading, “Caroline Forever Unzoned.”

It was an oddly emotional scene for a rally about zoning. Most people save their passionate advocacy for issues like abortion or gun control, not special use permits and setback requirements.

The general view of zoning as a dry, technical, apolitical issue is one reason it’s persisted unquestioned for so long. That probably explains why Caroline’s officials were blindsided by the huge, angry reaction to their zoning code proposal. To this day, it seems like they don’t quite understand the emotions they’ve kicked up.

One person at the town hall rally who did understand them was Amy Dickinson, even if she thought some of the anger expressed by anti-zoners wasn’t always productive.

Dickinson is a nationally syndicated advice columnist who makes a living helping people work through interpersonal problems. She’s also married to Schickel—and like her husband, she’s dead set against zoning.

Dickinson grew up on a dairy farm in a nearby town where, as in Caroline, most of the farms gradually went out of business. For farmers losing their livelihood, the ability to hold onto their property and leave it to their children becomes all the more important, she explains. So the idea that the town would then slap a bunch of rules on the one thing you still control felt both threatening and offensive.

“People take it personally,” she says. “Your land is all you have.”

Zoning Kills Dreams

Houston, Texas, is the one major city in the United States that never adopted a zoning code. Three times Houston has put zoning up to a referendum, and three times voters have rejected it.

In Gray’s anti-zoning book, Arbitrary Lines, there’s a picture of a Houston activist from one of those referendum campaigns, marching with a sign that reads “Zoning Kills Dreams.” That would become Caroline anti-zoners’ rallying cry, much to the frustration of those who support zoning.

“There’s a sign that says ‘Zoning Kills Dreams.’ Well, what is the dream you have that you think is not allowed? They don’t say,” says Harrison, the review board member.

It speaks to a difference in mentality and material circumstances of the two sides.

Caroline’s zoning supporters are typically either active or retired professionals. They live in the town and love it as much as anyone. But they also have no need to make a living there. That position lends itself to more restrictive notions of what should be allowed in Caroline: some homes, some businesses, some farms, and a lot of protected views and open space.

For these people, a zoning code is a pretty straightforward way of protecting the things they like about Caroline while banning the things they think will spoil it. And if anti-zoners are worried about losing the ability to do something on their land, they should say as much, and come to the table to get protections included in the draft code.

Things aren’t so simple for Caroline’s anti-zoners. The necessity of making a living from their land means they have to be pretty open and adaptable to change. They often don’t know what the future will bring. It’s often impossible for them to know how they might want to use their properties in the future.

Morse notes that his wedding venue had a couple of slow years right before the pandemic. If business dries up, he’ll have no choice but to sell Celebrations and move on. The more restrictions a zoning code puts on the use of his property, the fewer buyers there will be for it. That will tank the sale price of his land, leaving him with less to start a new business or retire on.

Freedom to do what he wants on his property is a valuable asset all on its own, and that freedom can’t coexist with zoning.

Caroline’s zoning debate is ongoing. The zoning commission approved a final draft code at the end of March 2023. The town board has started to hold hearings on it. Anything they approve will also have to be reviewed by the county government and various state agencies.

New York state law forbids zoning from being put before voters as a referendum. Peter Hoyt, a former town board member who opposes zoning, tells Reason that if a referendum were possible, it would probably be a pretty close vote.

Whatever the outcome, the zoning debate raging in Caroline is revealing. It shows how even in a small community without major enterprises or serious growth pressures, planners can’t adequately capture and account for everything people might want to do with their land.

There’s a gap between what zoners can do and what they imagine they can design. That knowledge problem hasn’t stopped cities far larger and more complex than Caroline from trying to scientifically sort themselves with zoning. They’ve developed quite large and complex problems as a result.

Caroline’s anti-zoners see the problems zoning has created elsewhere. They’re committed to fighting tooth and nail to preserve a freedom the rest of the country has lost.

They have dreams, and zoning might kill them.

The post The Town Without Zoning appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

What is already arguably America’s worst public transit project is about to get a whole lot more expensive.

The Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) is moving ahead with plans to build a 2-mile extension to the city’s 2.7-mile streetcar line, with an estimated price tag of $230 million. The Center Square reports that the first batch of that new spending—an $11.5 million contract awarded to a firm that will design the extension—was doled out last week. The project is being funded by a half-cent increase in the Atlanta sales tax, and the extension is scheduled to open in 2028.

Even if the extension doesn’t go over budget, $230 million for two miles of new streetcar track works out to a slobber-knocking total of $21,700 per foot.

And that only covers the construction costs. If the current Atlanta Streetcar is any indication, most of the operating costs for the extension will be covered by people who never ride it. The existing 2.7-mile loop through downtown Atlanta gets about 158,000 riders per year. Even if all of them pay the $1 per ride fare—and there is ample evidence that many do not—that wouldn’t come close to covering the system’s $5 million annual operating cost.

City officials say the extension—which will connect the streetcar to a nearby series of walking and biking trails in the middle of Atlanta—will increase ridership. But that shouldn’t be a sufficient justification for dumping another $230 million into a project that has plainly failed.

As Reason‘s Zach Weissmuller detailed in a documentary last year, the Atlanta Streetcar is comically out of date. It moves at 5 miles per hour and stops every quarter mile, making it no faster than the horse-drawn railways that crisscrossed cities in the 19th century.

And that’s when it runs at all. “It’s often stuck in traffic. Ridership has been anemic,” reports The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “In November, MARTA took the streetcar vehicles out of service because of safety concerns, though it began restoring rail service along the route last month.”

With a plethora of cheaper, faster, better transportation alternatives now available, it’s no wonder that so few people are choosing to ride the Atlanta Streetcar. Dumping another $230 million into a pointless extension of a useless service won’t change that.

The post Atlanta Plans To Blow $230 Million on 2-Mile Extension of Useless Streetcar appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Florianópolis, Santa Catarina—In some ways, this large island on the Atlantic coast is the opposite of what people imagine when they think of Brazil. Sure, it has white sand beaches and clear waters, but it is largely free of the crime and chaos found in big Brazilian cities—a low-key vacation respite for the nation’s elite. But having been invited here to speak at a conference and assigned a driver for the week, I ask him if there’s another side of Florianópolis that doesn’t show up on brochures.

“Oh, do I have a neighborhood for you,” says Alan Esteves, a rare English-speaking Brazilian cabbie.

Crossing the bridge from Florianópolis’ charming historic centro, Esteves drives down the highway ramp and into a barrio on the city’s western edge. This, he tells me, is Monte Cristo.

It began, according to a local realty firm, as a collection of shacks, but in 2007 the authorities completed some government housing here. The program replicated the modern U.S. approach—rather than building high-rise public housing, it offered low-rise detached suburban-style units. The homes featured German roofs, aping a common vernacular in this Eurocentric part of Brazil. Locals would be allowed to buy the housing at subsidized rates, encouraging homeownership.

Then something unplanned happened.

In the urban planning lexicon, there’s an acronym called ADUs, or “accessory dwelling units.” This describes any units that owner-occupants add to their main ones, like a garage or a backyard granny flat. As unauthorized additions mushroomed, the housing in Monte Cristo quickly became the ADU concept on steroids, with so many new additions as to make the area unrecognizable.

Favela is a Portuguese word that translates to “shantytown,” but that’s a location-specific way to describe an urban form that exists worldwide. The United Nations defines “slum” housing as that which is unstable, overcrowded, and lacking in basic sanitation. Brazilian favelas are thought of as slums, although the definition can be more tenuous.

“Specifically in the Brazilian context,” says urban planning journalist Gregory Scruggs, favelas are “a human settlement where there is not proper title to the housing stock.”

Beyond that, favelas have a certain aesthetic, giving them a know-it-when-you-see-it quality. Their construction is usually a mix of cinder blocks, a soil and clay composite called daub, and “hollow bricks” that might better be called structural clay tiles.

When I visit a construction goods store, a staffer explains that hollow bricks are three times cheaper than the more standard brick, but provide similar stability.

Another feature of favelas is that they evolve incrementally. They begin as small structures—sometimes literal huts—but owners build ADU-style additions as their family grows or they see financial opportunity in renting extra space or adding informal ground-level retail. Brazilian hillsides are especially conducive to this, with units literally stacked atop each other up the hill.

That incrementalism is also at work in relatively flat Monte Cristo. As Esteves drives, I see ADUs that have been added above, around, and in front of the initial structures. The builders used the typical favela materials, blending in no way architecturally with the pastel-colored homes built by the government.

According to Scruggs, who has both lived in and written about Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, Monte Cristo’s incrementalism is now getting formal traction. He cites the “half a good house” concept of the Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, who won the Pritzker Architecture Prize for his work.

When building modern units for slum dwellers, the idea goes, nonprofits should erect small homes with basic modern standards such as plumbing. But they should surround those homes with empty frames that let owner-occupants “expand,” favela-style, if they wish. Aravena helped design one such community in Chile at $7,500 per unit. Monte Cristo is another version of this idea, albeit an informal one.

That gets to the final way Monte Cristo, despite being a government complex, resembles a favela: Favelas are extralegal and are known throughout Latin America as “invasions.” Usually they occur on public land that is sitting unused. Sometimes they occur on private land, as part of populist revolts against large landowners, some of whom themselves amassed their holdings extralegally.

Once slum dwellers settle and start building, they are unlikely to be removed, since government institutions are weak and the political blowback is immense. So the favelas remain and evolve organically. The lack of titling can be a problem—because the land was seized illegally, no titles were issued, and it thus remains undervalued as a real estate asset, an issue documented by the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto.

Though Monte Cristo is a formal community, it has this “invasion” vibe. Tenants have added onto their units ad infinitum, with no regard to the setbacks, architectural standards, or maximum occupancy laws common in the United States.

Despite the problems associated with nebulous property rights, favelas represent a spontaneous, flexible form of housing that needn’t be confined to slum dwellers. I see in Monte Cristo a model for affordable housing programs in the U.S.—be they public, private, or nonprofit—where residents can add space gradually and rent it out to create income. Florianópolis, Scruggs argues, “is the ideal”: a model “where the public sector can provision land and some basic building standards but allow residents to build from there.”

Alain Bertaud, a planning professor at New York University, once noted that a form of this happens in U.S. housing projects already, as tenants continuously subdivide and sublet units. Monte Cristo shows how this can flower into something more open and affordable: by avoiding excessive rules in the first place.

The post How a Public Housing Project Became an Unplanned Neighborhood appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>The post Toronto after the 1st Wave: How COVID-19 affected three key markets appeared first on Spacing Toronto.

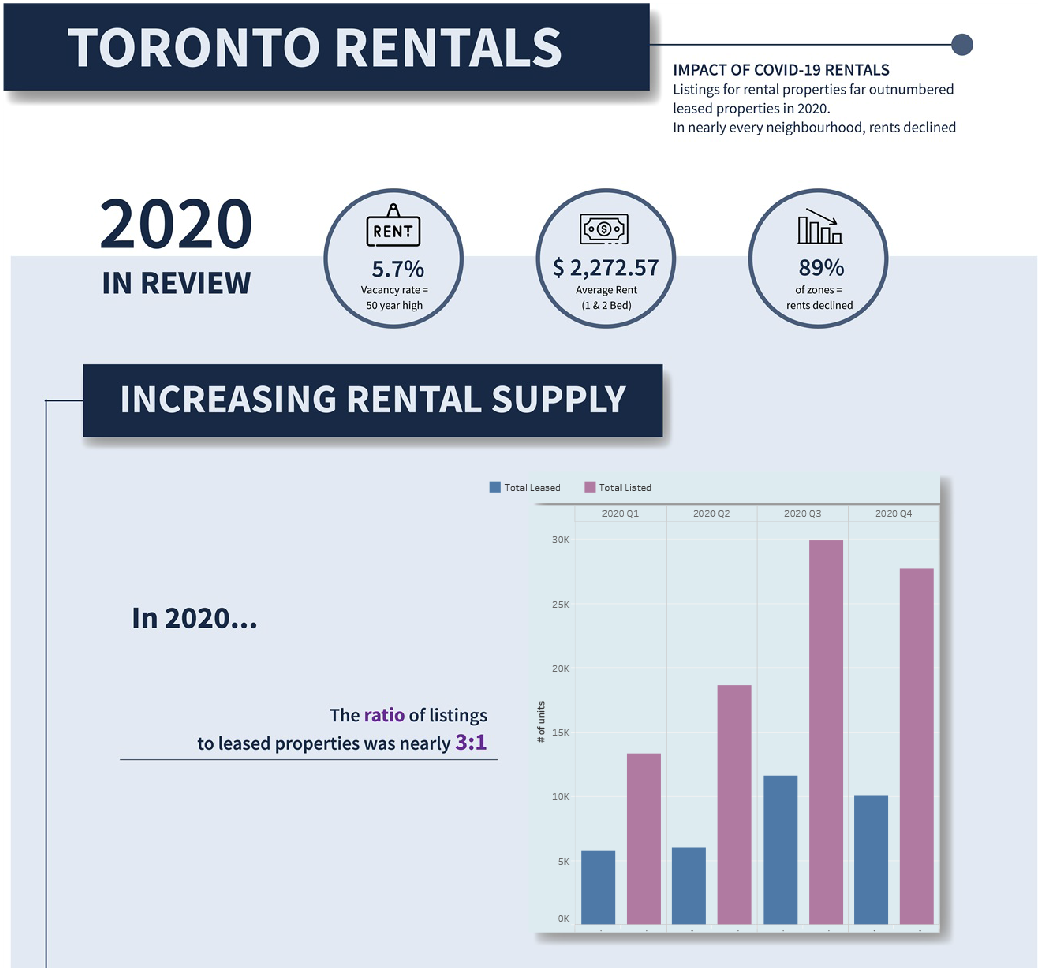

]]>In the fall of 2020, a University of Toronto research team set out to track key metrics from the city to assess the impact of COVID-19 on Toronto’s public health, economic well-being, and urban vibrancy. Since then, we published six data-driven dashboards documenting a wide range of topics—public health, mobility, restaurants, economic vibrancy, work, and housing. While the internet is flooded with devastating news surrounding this ‘once-in-a-century’ health crisis, our data analysis also suggests many once-in-a-century trends in Toronto’s housing, labour, and restaurant markets. Below, we identify some highlights of our findings to date.

HOUSING MARKET

Since the start of the pandemic, Toronto’s housing market has behaved very oddly, with home prices and rents going in opposite directions.

Data from our housing dashboard show that although COVID-19 caused a dip in home sales in April, 2020, the markets rebounded quickly and reached a record-high within two months.

With the significant market rebound, re-sale prices also rose. A 13.5% increase in average selling price was observed in 2020 compared to the previous year. The reasons might include the combination of low mortgage rates and work-from-home policies. Many middle- and high-income households also took advantage of the pandemic to accelerate their purchasing plans to buy first homes, second homes, or vacation homes.

Unusually, rising home prices did not boost rental rates. Our research shows that rents dropped significantly in both short-term and long-term rental markets.

Once-prime locations became less appealing when city life and commute to work are no longer priorities. In fact, the high population density and high costs of living in Toronto caused many residents to seek residence elsewhere, according to data from Statistics Canada. A look at geographical changes in rents reveals an 8.3% increase in rental prices in Scarborough compared to a 24.6% drop in Toronto’s city centre.

The divergent trends in home sales and rental prices reflect what economists refer to as a “K-shaped” recovery, in which certain industries pull out of a recession while others stagnate. While white-collar professionals in finance and tech are looking for bigger homes for their families to work from home, hourly workers are hit by low wages, reduced hours, or even loss of jobs as physical stores and restaurants close. According to a report published by the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario (FAO), the labour market showed a 27% decrease in low-wage jobs while employment in other wage categories increased by 1.4% this past year.

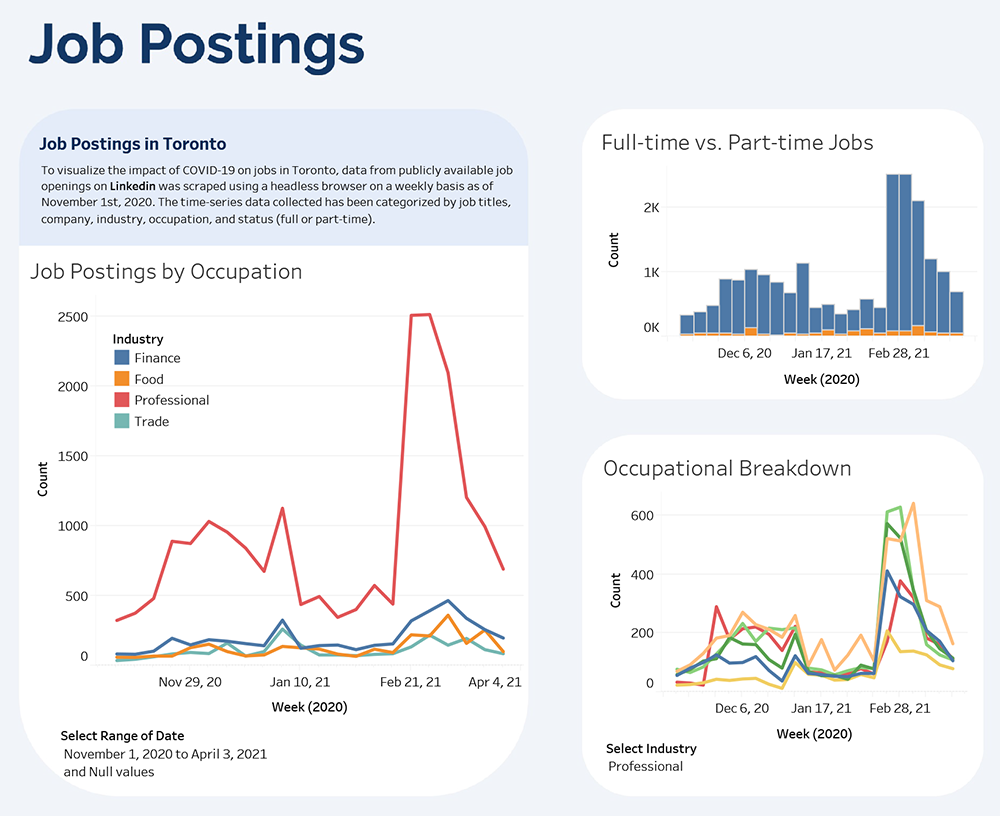

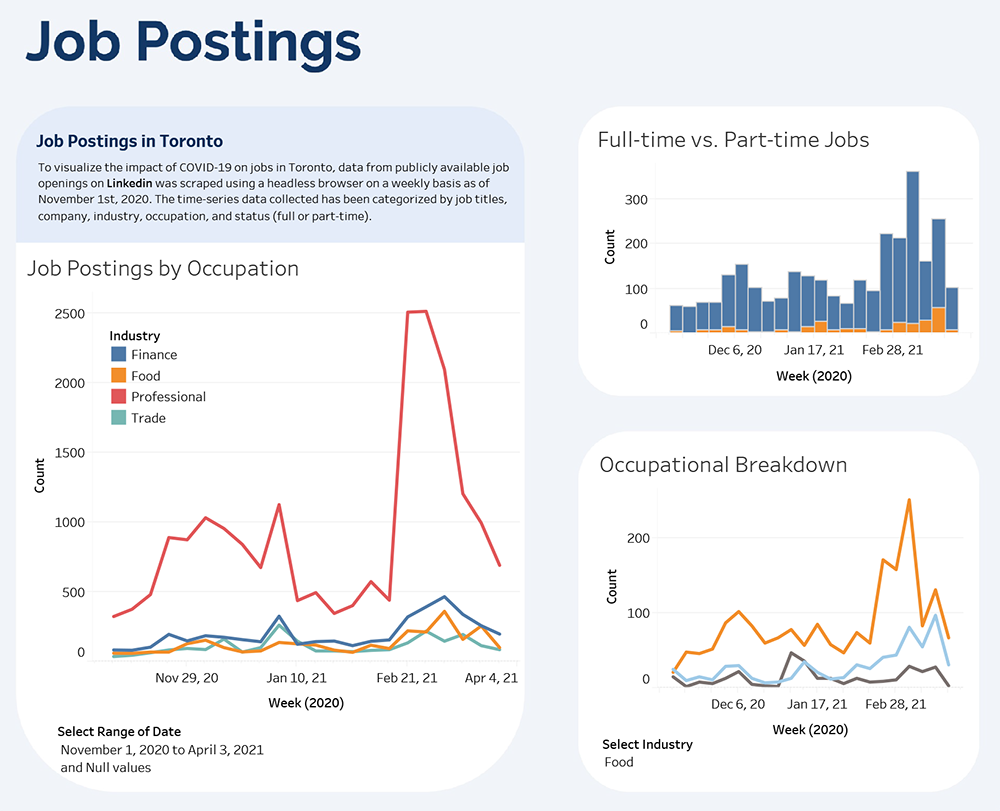

LABOUR MARKET

One way to assess the health of the labour market is by looking at new job postings online. By scraping job postings on LinkedIn from November 1st, 2020, we observed trends related to the K-shaped economic recovery in job market postings. Uncertainties still exist in the food service and retail trade industries due to on-going restrictions, however we observed a surge in white-collar job postings.

In February, 2021, the number of new postings doubled for professional jobs such as engineers, designers, consultants, and accountants. The surge reveals an opportunistic future post-pandemic—companies may have started to collect resumés in anticipation of improved prospects with respect to public health and economic activity.

Despite the surge in job postings, the concern is that hard-hit sectors, such as retail trade and food service, are not showing signs of recovery. With the roll out of vaccines and the eventual lifting of health/distancing restrictions, a recovery will take shape. However, to accelerate the recovery processes and to avoid permanent job losses, workers and small businesses would benefit from extended unemployment benefits or government subsidies.

RESTAURANT MARKET

We gauged the state of the city’s restaurant sector by monitoring restaurant closure status on Yelp. Our data showed that 244 new restaurants opened between May and November of 2020, against 214 closures. By looking at maps of restaurant openings and closures, the most-sought after locations—major subway lines and popular tourist areas—have the highest rates of new openings. As the pandemic continues, businesses are changing to adapt to the new normal. By examining the types of restaurants that opened and closed, we saw a shift from traditional sit-down restaurants (e.g. Chinese, Hong Kong, and Breakfast & Brunch) to more grab-and-go styles (e.g. sandwiches and cafes).

In addition, due to the rise of ‘on-demand culture,’ COVID-19 has driven gig economy activities and is contributing to the growth of food delivery services such as UberEats and DoorDash. The availability of gig worker positions (e.g. food delivery driver) may also offer some financial relief for those seeking additional income. At the same time, this labour trend presents new challenges related to low-wage gig economy work, as well as COVID-19 safety issues.

Interestingly, restaurants located in food courts near major subway stations have shown a 100% survival rate. Restaurants at these locations might be chains with owners who wish to keep prime locations despite temporary losses. The Commerce Court near Union Station, for example, has a great number of restaurants, most of which are chain outlets that offer quick bites such as Fast Fresh Foods and Z-Teca Gourmet Burritos.

Small- and medium-sized businesses are the backbone of our economy. To help these businesses endure the pandemic, consumers need to be conscious of whom they support. The notion of buying locally should be encouraged to sustain local business owners. In addition, local restaurants will likely benefit from partnerships with food delivery services to offer an online shopping experience for consumers. At the start of the pandemic, some restaurant owners reported that more than half of their revenues came from sales on these apps. Perhaps as a short-term relief, the government should continue to cap delivery commission fees for areas that are impacted by public health restrictions. In addition, to avoid high commission fees, a long-term solution is for restaurants to start their own delivery services. A vegan pizza restaurant in Toronto, for example, coordinated delivery with neighboring restaurants.

Although Ontario is once again in a period of lockdown, our analysis suggests that some industries and sectors are likely to be more resilient to COVID-19 shocks. Based on patterns observed following each of the first two waves, and with the current rollout of vaccines, the City of Toronto’s economy is likely to recover quickly from the COVID-19-triggered “recession” once public health risks are further reduced and health restrictions are lifted.

As cities start to recover, we have an opportunity to assess changes and evaluate the effectiveness of government responses. Our research, Toronto After the First Wave: Measuring Urban Vibrancy in a Pandemic, allows for retroactive and retrospective analysis on how the pandemic had impacted key sectors in the city. As we continue to track Toronto’s road to recovery, we hope to help policy makers and public health officials become better informed when making decisions in the context of COVID-19.

Youjing Li is a graduate student at the University of Toronto’s iSchool. She holds a Bachelor of Engineering degree from the University of Waterloo. Follow her on twitter at @li_youjing. Shauna Brail is an associate professor at the Institute for Management & Innovation, University of Toronto. She is also an affiliated faculty at the Innovation Policy Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto. Follow her on twitter at @shaunabrail.

Toronto After the First Wave, led by Prof. Brail, is funded in part by MITACS. Youjing is a research assistant responsible for data visualization. Other team members include Cindy Thai, Ecem Sungur and project alumna Katherine Hovdestad.

The post Toronto after the 1st Wave: How COVID-19 affected three key markets appeared first on Spacing Toronto.

]]>The post LORINC: Which green standard will reduce Toronto’s carbon? appeared first on Spacing Toronto.

]]>

Few would argue that the City of Toronto’s goal of reducing building-related carbon emissions to zero by around 2030 is a worthy, though challenging, goal. Built form, after all, accounts for about 40% of all greenhouse gases. But how do we know when a building has actually stopped emitting carbon? And what does net zero really mean?

In a jurisdiction with relatively clean electricity, one answer seems straightforward enough: heat only with electrons; don’t build in a field in the middle of nowhere; use construction materials that sequester instead of consume carbon.

But we don’t live in a simple world, so the political economy around green building policies is a bewildering maze of acronyms, competing certification protocols, and sly gaming strategies, all set against the technically daunting backdrop of building science and building codes. LEED, PHI, PHIUS, TEDI, TEUI, GHGI, TGS. The list goes on, making it nearly impossible for a lay person to determine whether the city is actually moving toward its stated goal.

For years, LEED has been the best known green building standard, implemented by developers and architects according to a complex framework set out by the Canadian Green Building Council. Problem is, many builders now understand how to manipulate the points-based LEED certification system to create projects that are marketed to investors or tenants as environmentally friendly, but aren’t necessarily low-emission structures.

A 2013 study on New York City’s record with this approach concluded “that LEED building certification is not moving NYC toward its goal of climate neutrality.” A 2019 Finnish literature review — entitled, “Are LEED-certified buildings energy efficiency in practice?” — came to a similar conclusion, noting that lower levels of LEED certification produced “questionable” gains.

Passive House, a 30-year-old German standard, has delivered far more consistent results using a combination of features that include extremely tight building envelopes, thick insulation, triple-pane windows, passive solar orientation and high-efficiency ventilation and heat recovery systems. This design methodology, which can slash energy consumption by as much as 90%, has become commonplace in northern Europe, and is gaining traction in the U.S. and British Columbia.

The wrinkle is that it’s still difficult to obtain some types of Passive House certified components in North America, and the pool of contractors trained in this kind of construction is small. Some critics also argue that some Passive House-certified buildings contain a great deal of embodied carbon because of the large quantities of insultation required in such structures, although there’s growing interest in work-arounds that achieve similar energy reductions.

Yet both LEED and Passive House are voluntary – it’s up to the developer to figure out whether there’s a return on the additional upfront cost, either in terms of a building’s marketability or its operational expenses.

A slightly more systematic way of pushing down building-related carbon has come in the form of Toronto’s deep lake water district cooling infrastructure, which has allowed many of the office towers in the financial core to buy heating and cooling from Enwave, thereby displacing natural gas consumption.

The network is growing west, with the construction of The Well, at Spadina and Front, a massive RioCan/Allied/Tridel joint venture that sits on top of a 7.6 million litre lake water cistern that will supply cooling for buildings proposed for King West. For office buildings, the math works, and so while hook-ups are voluntary, they make financial sense. Condo towers, however, have proven more difficult to recruit, because the ownership is fractured.

The City’s attempt to impose some regulatory order on all this activity is the Toronto Green Standard, which establishes minimum performance standards for new construction that exceed the pathetically modest ones in the Ontario Building Code. Since first approving the TGS in 2009, council has tightened the policy several times, making it gradually more demanding by adding higher voluntary “tiers” paired with financial incentives, such as development charge debates.

As of 2018, TGS Version 3 came into effect, with a four-tier system of performance standards for a range of metrics – air quality, energy efficiency, carbon emissions, solid waste, etc. Only tier 1 is mandatory for every project, for now. But TGS V3 borrows heavily from B.C.’s “energy step code,” which is, in effect, an escalator: over the next several years, the minimum standards will increase in predictable increments, until all new buildings will be net zero by 2032.

Because the TGS V3 also operates like an escalator, projects that commence later in this decade, including privately developed ones, will have to satisfy the more demanding minimums that currently only apply to city-owned properties. After 2030, the net or near zero rules will be required of every new project.

Some aspects of the TGS approach are straightforward attempts to show leadership and prime the market pump for more energy and carbon friendly products, like ua high-performance windows. For example, buildings developed by the City or its agencies have to meet more stringent standards that are, as of now, still voluntary for private builders. Other features, however, are just plain complicated, as a scan of the side-by-side comparison between the TGS v3 and LEED Version 4.0 for private mid and high-rise buildings demonstrates.

There are also ambiguities in the policy. For example, on Toronto Community Housing revitalization projects (e.g., Regent Park, Lawrence Heights), new rental towers that will be run by TCH must comply with higher standards, but the market buildings, which sit on public land that the agency is selling to private developers, may not. The same is true for the new Housing Now projects going up on city-owned land.

In other words, two buildings – one market, the other rent-geared-to-income – may go up next to one another in the next phases of, say, the Regent Park revitalization, but the subsidized one will have better energy efficiency features (and therefore lower operating costs) than its privately owned neighbour.

Waterfront Toronto, meanwhile, is adopting a slightly different approach, which it recently published, for precincts like Villiers Island and Quayside. In the Sidewalk Labs era, the agency wanted to promote Passive House-grade development, but has since revised its thinking somewhat. Now, developers will be expected to meet the toughest of the TGS tiers (4) after 2025, which are similar to Passive House in terms of performance but won’t require certification as such. WT’s Green Building standards lay out requirements for areas such as building resilience, EV infrastructure, and waste management.

Aaron Barter, WT’s director of innovation and sustainability, says WT will also be asking developers to disclose the embodied carbon in their projects, which means considering alternatives to high emitting materials like steel. “This is the direction the market is headed.”

Besides all the technical minutiae, there is a hugely impactful detail in WT’s carbon reduction plan for these new neighbourhoods: no natural gas hook-ups. The entire area, Barter says, will be powered by electricity.

While the province does rely on natural-gas fired generators — including the Portland Energy Centre, sitting only a few hundred metres from Villiers — for load balancing, Ontario’s electricity system isn’t a heavy carbon emitter, so WT’s development plan is not only a big win, but also easy to understand.

Yet WT’s gas-free development plan should serve as a bracing reminder that, despite all the various green building strategies, most of Toronto’s low-rise neighbourhoods consist of brick homes and apartments hooked up to a far-flung natural gas distribution network that is worth billions in sunk costs, and isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

It’s certainly true that many homeowners, residential contractors and even apartment managers are adding insulation, replacing windows, and installing EV charging in garages. But natural gas, as a 2018 City report notes, “continues to be the largest source of emissions community-wide, accounting for approximately 50 per cent of Toronto’s total GHG emissions.”

Natural gas is also the carbon source that remains most stubbornly beyond the reach of the sorts of policy sticks and carrots deployed in recent years to improve energy efficiency in buildings. Even the recommendations of home energy audits tend not to get at our gas dependency beyond recommending higher performing furnaces.

The related point is the harsh financial reckoning that will make its presence felt on the gas bills of hundreds of thousands of homeowners (and, indirectly, the rents of tenants) as greenhouse gas levies more than quadruple the price of carbon, from $40 today, to $170 in 2030.

Maybe that’s when Torontonians will finally try to decipher all the dense techno-speak in our green building codes and figure out how those acronyms can hedge their exposure to the carbon that’s hardwired into the urban environment.

The post LORINC: Which green standard will reduce Toronto’s carbon? appeared first on Spacing Toronto.

]]>