Theodore Roosevelt was president at the start of the Celebrity Age, and at the start of much of the modern image of the presidency. The White House was just beginning to be called that (rather than the Executive Mansion); Roosevelt’s renovations on the building created the West Wing. And his daughter, Alice, created one model for presidential relatives over the next century.

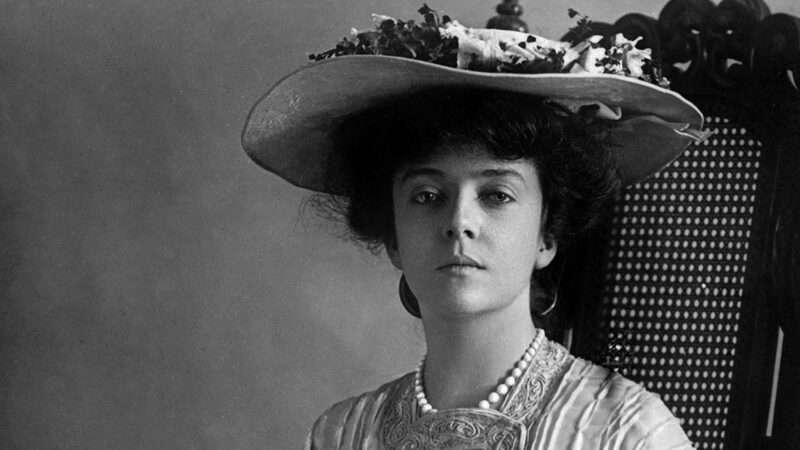

Aged 17 when her father became president, she was a gift to the Washington press corps. Photogenic and charming, she was nicknamed “Princess Alice” in the papers. She was invited to Edward VII’s coronation (she did not attend), and the German kaiser had her christen his yacht. Her hobnobbing with royalty didn’t sit well with her father’s man-of-the-people pose, but he could do nothing to stop his daughter’s fame.

According to White House Wild Child, Shelley Fraser Mickle’s new biography of the presidential daughter, Alice’s “celebrity had certainly surprised him. He hadn’t seen it coming. Whenever Alice appeared, crowds gathered to cheer her. Dresses and gowns appeared in ‘Alice blue.’ Her face gazed out from cards packaging candy bars. Songs were written about her, and her picture was featured on their sheet music. Her face was centered on magazine covers.” Mickle sees in Alice the forerunner of Jackie Kennedy, Princess Diana, and other trendsetting beauties and influencers.

The president was happy to deploy Alice tactically, to charm guests and diplomats. Such diplomatic tactics went the other way too: She was showered with gifts on foreign visits, gifts she referred to as her “loot.” The Cuban government gave her a magnificent set of pearls for her wedding. The Foreign Emoluments Clause apparently didn’t apply to her.

Taking advantage of her situation seemed only natural. Alice’s father had to tell her not to ride the train without a ticket. (While presidents were entitled to free travel, their kids were not.) But this was when a presidential daughter might still jump on a train with friends, rather than be accompanied by a phalanx of Secret Service agents.

Mickle’s book is part biography and part psychological study, the story of a woman growing up in impossible privilege but with a life marked by tragedy. At Alice’s birth, her mother slid into a coma and died two days later. Theodore’s mother died the same day, a double blow. He responded by avoiding his baby daughter, leaving her in his sister’s care while he fled into his political work and to his ranch out west.

He reappeared in her life three years later to introduce her to a new stepmother. A clutch of younger siblings soon followed. Mickle makes much of how this must have damaged Alice, particularly her father’s reluctance even to speak her name. (She had been named for her mother.)

***

Mickle’s book is a study in how a republic treats its leaders’ families. The nickname “princess” shows the knife-edge between democracy and dynasty, a line that presidential families have struggled to walk ever since. Alice would have her debutante ball in the White House, and she wanted a new floor installed. She approached the speaker of the House, asking him to appropriate funds for this purpose. “Alice used her every ploy on him, enjoying her first taste of lobbying,” Mickle writes, “but the Speaker held firm, refusing the funds.”

She didn’t get her way that time, but her desires were voracious. “I want more,” she scribbled in her diary. “I want everything.” She spent through her enormous allowance, and she saw nothing wrong with receiving high-value presents by dint of her position. Foreshadowing the practices of generations of socialites to come, “She tipped off newspapers about where she’d be and what she’d be up to, then pocketed the cash for the info.”

She also enjoyed making a spectacle of herself and pushing boundaries. Driving around Washington with a girlfriend in a sports car, showing up at parties with her pet snake around her shoulders, smoking in public: She was attention seeking (and attention getting). “In one fifteen-month period,” Mickle tells us, “she went to 407 dinners, 350 balls, 300 parties, and 680 teas, and she made 1,706 social calls.”

Alice was determined to get while the getting was good, fishing for a husband in the pond of D.C.’s eligible bachelors. She wanted one with money, and one who could be president himself one day. Her goal was getting back to the White House. (Of course, she never did.)

She picked Nicholas Longworth, an Ohio congressman 15 years her senior. Their White House wedding was the social event of the season. But Longworth turned out not to be on the presidential track, and he was an unfaithful alcoholic.

Alice’s life turned to disappointments. She became renowned for her caustic comments as she got older, and the wit did not disguise her bitterness. Her marriage was unhappy; her late-in-life child was the product of an affair. Her daughter died of a drug overdose in her 30s. Her father’s presidency was always the golden moment she wanted to recapture. She continued to engage with the politics of the day, joining the fight against the League of Nations and later writing newspaper columns against her cousin Franklin’s presidential candidacy. Richard Nixon was a friend for decades, and he invited her to his inauguration. She remained a Washington figure, still hovering in the orbit of those in power despite having no official role.

The legacy of “Princess Alice” raises questions we still grapple with today. How much should presidential family members trade on their name? Could that even be avoided? Of course, gifts and favors will materialize for those close to power, whether they’re sought or not. Being whisked around by motorcade and private jet these days means there’s no escaping their link to the president. It’s easy, I’m sure, to lose sight of what’s normal.

What we should accept as normal is itself an important question. With presidential son Hunter Biden in the news for crossing the line to the point of criminal indictment, we should think more seriously about where exactly that line should be drawn. There are few laws specifically dedicated to the activities of first family members. Should children be barred from particular careers? From running for office themselves? What about siblings? (When presidential kids aren’t in the news, there are embarrassing presidential brothers in the Billy Carter mold.) Even when an activity isn’t officially forbidden, the tang of shadiness or self-dealing will linger if a family member seems to be cashing in. Individuals may be chosen by the ballot, but they come with an unelected supporting cast.

Had her father not been president, Alice Roosevelt still would have made the society pages. She would have been a Park Avenue debutante. She would have been steered toward marriage with the scion of a prominent family, or perhaps a titled European. A future of philanthropic work and society events would await. But she would have wanted more.

White House Wild Child: How Alice Roosevelt Broke All the Rules and Won the Heart of America, by Shelley Fraser Mickle, Imagine, 256 pages, $27.99

The post How To Be the President's Kid appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

After a not-quite accidental encounter, an unassuming Oxford student named Ollie (Barry Keoghan) befriends a popular classmate, the handsome and wealthy Felix (Jacob Elordi). Felix invites Ollie to spend the summer with him at Saltburn, his eccentric family’s opulent mansion in the English countryside. Murder and madness ensue.

Critics correctly noted that Amazon Prime Video’s Saltburn bears a striking resemblance to another film that depicts an ingratiating young man’s quest for social acceptance (and it’s a mild spoiler to mention this, so be warned): The Talented Mr. Ripley. But as far as the film’s message is concerned, the critics wildly missed the mark, describing Saltburn as an eat-the-rich comedy that “skewers” the ultra-wealthy and rejoices in “class war.”

This interpretation could not be more wrong. Felix and his family are not villains—they are victims of scheming outsiders who covet all they have and seek to destroy it. If anything, the rich people in the film are toonice and generous; they should have thrown Ollie out on day one. Forget Ripley; Saltburn has much more in common with the critically acclaimed but widely misinterpreted Parasite, in which a wealthy Korean household is preyed upon by a lower-class family (the eponymous parasites). Both films are, if anything, reactionary, something almost no one seems to have noticed.

The post Review: Is <i>Saltburn</i> an Eat-the-Rich Comedy? Not Quite. appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

For four seasons, Apple TV+’s For All Mankind has presented an alternate history of the space race, starting in a world where Russia, not America, put the first person on the moon. That single incident creates a domino effect on history: In the first season, set in the 1960s and ’70s, the United States allows women into the NASA pilot program. In the 1980s, both America and Russia build small manned bases on the moon. By the 1990s, American and Russian space programs are competing not only with each other but with private space tourism efforts, including a massive orbital hotel.

In the fourth season, set in 2003, the U.S., Russia, a private space exploration company, and North Korea have set up a joint settlement on Mars. But tensions run high when the workers revolt, staging a strike just as an asteroid ripe for mining drifts through the solar system. There are black market operations and an illegal speakeasy, high-stakes geopolitical negotiations, and deadly outer-space operations. The show presents space exploration, under whatever national or corporate aegis, as risky, difficult—and gloriously necessary for the growth of humanity.

The post Review: <i>For All Mankind</i> Offers an Alternate History of Moon Exploration appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Vote Gun: How Gun Rights Became Politicized in the United States, by Patrick J. Charles, Columbia University Press, 488 pages, $35

The National Rifle Association (NRA) “favored tighter gun laws” in the 1920s and ’30s, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof wrote in 2018. But since the 1970s, Kristof complained, the NRA “has been hijacked by extremist leaders” whose “hard-line resistance” to even the mildest gun control proposals contradicts “their members’ (much more reasonable) views.”

Other NRA critics have told the same story. That widely accepted account, U.S. Air Force historian Patrick J. Charles argues in Vote Gun, is “based more on myth than on substance.” In reality, he shows, the NRA’s fight against gun control dates back to the 1920s. But in waging that battle, the organization tried to project a reasonable image by presenting itself as open to compromise. That P.R. effort, Charles says, is the main source of the erroneous impression that “the NRA was once the chief proponent of firearms controls.”

Charles also aims to debunk the idea that the NRA’s power derives from its ability to mobilize voters against elected officials who defy its wishes. Since it “commandeered the political fight against firearms controls from the United States Revolver Association” a century ago, he says, the NRA has been adept at defeating proposed gun restrictions by encouraging its members to pepper legislators with complaints. While such direct communications tend to make a big impression, Charles argues, they are a misleading measure of the electoral penalty that politicians are apt to suffer by supporting gun control.

Vote Gun—which covers the first eight decades of the 20th century, ending with Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980—presents a wealth of new material to support its main theses. But the book is marred by many small mistakes, which appear on almost every page and typically involve misused, misspelled, misplaced, or missing words. More substantively, Charles is harshly critical of the NRA’s rhetoric and logic but pays little attention to similar weaknesses in the arguments deployed by supporters of gun control.

In his prior work, Charles has portrayed the NRA’s understanding of the Second Amendment as a modern invention. He alludes to that position in Vote Gun when says the “broad individual rights view” accepted by the U.S. Supreme Court is based on “historical sleight of hand.”

Contrary to what the Court has held, Charles thinks the Second Amendment was not originally intended to protect an individual right unrelated to militia service. That idea, according to his 2018 book Armed in America, first emerged in the 19th century. Even then, Charles says, the Second Amendment was seen as consistent with regulations opposed by the contemporary gun rights movement. His lack of sympathy for the idea that the right to armed self-defense should be treated like other civil liberties colors Vote Gun‘s ostensibly neutral account.

***

As early as 1924, NRA Secretary-Treasurer C.B. Lister was declaring that “the anti-gun law can be intelligently viewed only from the standpoint of a public menace.” The organization soon began acting on that attitude by resisting new gun legislation.

Charles argues that the conventional narrative exaggerates the significance of the 1977 NRA convention in Cincinnati, where “hardline gun rights supporters” replaced leaders they perceived as insufficiently zealous in protecting the Second Amendment. “Many academics,” he says, see that development as “a gun rights revolution of sorts—one that forever transformed the NRA from a politically moderate sporting, hunting, and conservation organization into an extreme, no-compromise lobbying arm.” That view, he suggests, is belied by the NRA’s prior five decades of lobbying against gun restrictions and its explicit adoption of a “no compromise” stance seven years earlier.

Here Charles’ sloppy writing obscures his meaning. “This is not to say that the Cincinnati Revolt is insignificant in the pantheon of gun rights history,” he writes. “It most certainly is.” He presumably means that it is not insignificant. That’s just one of numerous errors that would have been caught by any reasonably careful editor or proofreader. Although generally minor, they sometimes raise questions about the book’s sources.

According to Charles, for instance, a member survey that the NRA conducted in 1975 included this question: “Do you believe your local police need to carry firearms to arrest and murder suspects?” We can surmise that the word and, which radically changes the meaning of the question, was included accidentally. But it’s not clear whether the accident should be attributed to Charles or the NRA.

Despite such puzzles, Charles is on firm ground in arguing that the NRA has frequently portrayed even relatively modest regulations as the first step toward mass disarmament. But he also shows the NRA has blocked policies that would have substantially limited the right to keep and bear arms. Charles seems loath to acknowledge that such proposals lent credence to the NRA’s warnings.

The National Firearms Act of 1934, for example, originally would have covered handguns as well as machine guns and short-barreled rifles. The law required registration of those weapons and imposed a $200 tax on transfers, which was designed to be prohibitive, amounting to about $4,600 in current dollars. Had Congress enacted the original version of that bill, possession of what the Supreme Court would later describe as “the quintessential self-defense weapon” would have been sharply restricted.

More generally, Charles depicts the NRA’s concerns about gun registration as overblown, verging on paranoia. But while registration is not necessarily a prelude to prohibition, it is a practical prerequisite for any effective confiscation scheme, and such schemes were seriously entertained even after the debate over the National Firearms Act.

***

In 1969, a bipartisan majority of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, which President Lyndon B. Johnson had appointed the previous year, recommended confiscation of handguns from those who failed to demonstrate “a special need for self-protection.” Charles says Richard Nixon, Johnson’s successor, was initially inclined to support a handgun ban. Although “his advisors convinced him otherwise,” the policy remained a live issue.

The National Coalition to Ban Handguns was founded in 1974. Two years later, Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson urged Congress to “immediately ban the import, manufacture, sale and possession of all handguns.” Congress never did that. But cities such as Chicago and Washington, D.C., did ban handguns via laws that the Supreme Court eventually overturned. In this context, it is not hard to understand why the NRA objected to national gun registration, which was backed by prominent legislators such as Sen. Joseph Tydings (D–Md.) and Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott (R–Pa.).

Charles notes that Scott repudiated his support for registration in 1970 because he worried that it could cost him reelection, and he describes several similar reversals. But Charles argues that the NRA’s bark was worse than its bite. Although the idea that the NRA and other gun rights groups could swing elections became widely accepted beginning in 1968, he says, a closer look at races where they supposedly did so makes that proposition doubtful.

Charles is similarly skeptical of the idea that policies such as federal restrictions on the inexpensive handguns known as “Saturday night specials” and California’s 1967 ban on carrying loaded firearms without a permit harked back to the racist roots of gun control. Scholars such as Fordham University law professor Nicholas Johnson and UCLA law professor Adam Winkler have suggested a racial motivation can be inferred from the context of those policies. While the circumstantial evidence in both cases strikes me as pretty strong, Charles apparently would be satisfied only by explicit statements of anti-black animus.

Charles’ skepticism does not extend to the reasoning behind gun restrictions that the NRA often opposed and sometimes accepted. Once Congress excised handguns from the National Firearms Act, for instance, the rationale for restricting short-barreled rifles—that they were relatively easy to conceal—became nonsensical. And does anyone seriously suppose that the 1968 ban on mail-order rifles had a significant impact on violent crime?

Nor does Charles delve into the logic of the “prohibited persons” categories that were established by the Gun Control Act of 1968 and broadened by subsequent legislation. You might think a policy of disarming millions of Americans with no history of violence would merit a little more discussion, especially since the NRA supports that policy, notwithstanding the organization’s supposedly resolute defense of gun rights.

Such compromises, which make the right to armed self-defense contingent on legislative fiat, help explain the emergence of groups that position themselves as more steadfast than the NRA, such as the Second Amendment Foundation and Gun Owners of America. Charles presents compelling evidence that the NRA’s resistance to gun control long predates the 1970s. But so does the NRA’s acquiescence to gun control, which continues to this day.

The post The 'No Compromise' NRA Is Neither New nor Uncompromising appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

In Rutherford County, Tennessee, kids as young as 7 years old were getting thrown in jail for incredibly minor offenses—stealing a football or pulling someone’s hair. Some kids were even jailed for acts that weren’t crimes at all, such as failing to stop an after-school fight. Worse still, the kids were frequently put in solitary confinement, even though that’s explicitly prohibited for children under Tennessee law.

Not only were these jailings illegal, but pretty much everyone working in the Rutherford County Juvenile Court knew it—including the county’s sole juvenile court judge, Donna Scott Davenport.

In The Kids of Rutherford County, a four-part podcast series from Serial Productions and The New York Times, Meribah Knight examines how so many kids could be unlawfully detained and why it took so long to stop the practice.

The podcast follows two public defenders, Wes Clark and Mark Downton, who eventually launched a successful lawsuit against the county after years of maddening attempts to convince Davenport that her practices were illegal.

Thanks to Clark and Downton’s suit, Rutherford County is no longer illegally detaining its children on minor offenses and Davenport is no longer on the bench. But the pair didn’t end up with an unalloyed victory. The $11 million payout that Clark and Downton won in court? Only 23 percent of the eligible recipients could be contacted to make claims, so just $2.2 million was distributed to the jailed kids.

The Kids of Rutherford County showcases just how difficult it is to force broken government systems to change, and how difficult it is to make the victims of injustice whole.

The post Review: Exposing a Broken Juvenile Court System appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Unwired: Gaining Control over Addictive Technologies, by Gaia Bernstein, Cambridge University Press, 248 pages, $24.95

“For over a decade,” Seton Hall Law School professor Gaia Bernstein recalls in Unwired, “I often sat down to write at my regular table at the coffee shop near my apartment. I took out my laptop, my iPhone, and my Kindle. I wrote down my list of tasks for the day. But then two and a half hours later, with little writing done and feeling drained, I wondered what happened. The answer was usually texts and emails, but more than anything, uncontrollable Internet browsing: news sites, blogs, Facebook. Every click triggered another. I no longer do this. At least, I try my best not to.”

Although Bernstein calls her behavior “uncontrollable,” she also says she managed to control it. But after several years of studying “technology overuse” and advising people on how to limit their children’s “screen time,” she has concluded that self-discipline and parental supervision are no match for wily capitalists who trick people into unhealthy attachments to their smartphones and computers. The solution, she believes, must include legal restrictions and mandates. Without government action, she says, there is no hope of “gaining control over addictive technologies.”

To make her case that the use of force is an appropriate response to technologies that people like too much, Bernstein mixes anecdotes with a smattering of inconclusive studies and supposedly earthshaking revelations by former industry insiders. It all adds up to the same basic argument that has long been used to justify restrictions on drug use, gambling, and other pleasurable activities that can, but usually do not, lead to self-destructive, life-disrupting habits: Because some people do these things to excess, everyone must suffer.

Like drug prohibitionists who assert that the freedom to use psychoactive substances is illusory, Bernstein is determined to debunk the notion that people have any real choice when it comes to deciding how much time they spend online or what they do there. If you believe that, she says, you have been fooled by “the illusion of control,” which blinds you to the reality that “the technology industry” is “calling the shots.”

Given the underhanded techniques that designers and programmers use to lure and trap the audience they need to generate ad revenue and collect valuable data, Bernstein argues, people cannot reasonably be expected to resist the siren call of the internet. The result, she says, is an increasingly disconnected society in which adults stare at their phones instead of interacting with each other and children face a “public health crisis” caused by their obsession with social media and online games.

One problem for Bernstein’s argument, as she concedes, is that the concept of “screen time” encompasses a wide range of activities, many of which are productive, edifying, sociable, or harmlessly entertaining. Another problem, which Bernstein by and large ignores, is the fine line between “abusive design,” which supposedly encourages people to spend more time on apps, social media platforms, or games than they should, and functional design, which makes those things more attractive or easier to use.

Bernstein warns that ad-dependent and data-hungry businesses are highly motivated to maximize the amount of time that people spend on their platforms. So they come up with “manipulative features,” such as “likes,” autoplay, “pull to refresh,” the “infinite scroll,” notifications, and algorithm-driven recommendations, that encourage users to linger even when it is not in their well-considered interest to do so. But those same features also enhance the user’s experience. If they didn’t, businesses that eschewed them would have an advantage over their competitors.

Bernstein claims that autoplay, for example, serves merely to increase revenue by boosting exposure to advertising. Yet she repeatedly complains about autoplay on Netflix, which makes its money through subscriptions. The company nevertheless has decided that it makes good business sense to cue up the next episode of a series after a viewer has finished the previous one. Other streaming services have made the same decision.

Bernstein says that sneaky move gives people no time to decide whether they actually want to watch the next episode. But a lag allows viewers to stop autoplay with the press of a button. If they are not quick enough, they still have the option of choosing not to binge-watch You or The Diplomat, a decision they can implement with negligible effort. As a justification for government intervention, this is pretty weak tea.

One of the horror stories scattered through Unwired poses a similar puzzle. Daniel Petric, an Ohio teenager, was so obsessed with Halo 3 that he ended up playing it 18 hours a day. After his concerned father “confiscated the game” and locked it in a safe, Bernstein notes, Petric shot both of his parents, killing his mother.

Since Halo is an Xbox game, Bernstein cannot claim that its designers were determined to maximize ad revenue by maximizing play time. Rather, they were determined to maximize sales by making the game as entertaining as possible. While that may be a problem for some people in some circumstances, making video games as boring as possible is plainly not in the interest of most consumers, which is why it is a bad business model. But by Bernstein’s logic, pretty much anything electronic that holds people’s interest is suspect.

Bernstein does not propose a ban on compelling video games or binge-worthy TV shows. But she has lots of other ideas, including government-imposed addictiveness ratings, restrictions on the availability of online games (a policy she assures us is not limited to “totalitarian regimes like China”), mandatory warnings that nag people about spending too much time on an app or website, legally required default settings that would limit smartphone use, and a ban on “social media access by minors.”

Bernstein also suggests “prohibiting specific addictive elements,” such as loot boxes, autoplay, engagement badges, alerts, and the infinite scroll. And she wants the government to consider “prohibiting comments and likes on social media networks,” which would make social something of a misnomer. If those steps proved inadequate, she says, legislators could take “a broader catch-all approach by prohibiting any feature that encourages additional engagement with the platform”—a category capacious enough to cover anything that makes a platform attractive to users.

Other possibilities Bernstein mentions include “a federal tort for social media harm,” a Federal Trade Commission crackdown on excessively engaging platforms, and an effort to break up tech companies through antitrust litigation. She hopes the last strategy, which so far has proven far less successful than she suggests it could be, would create more competition, which in turn would help replace free services that rely on advertising and data harvesting with services that collect fees from users.

But why wait? “Social media is free,” Bernstein writes. “Games are mostly free. But what if they were not? What if users had to pay?” Just as “taxes on cigarettes made them prohibitively expensive” and “effectively reduced the number of smokers,” she says, a “pay-as-you-go model” would deter overuse, especially by teenagers.

Might some of these policies pose constitutional problems? Yes, Bernstein admits. “As laws and courts continuously expand First Amendment protection,” she says, the fight to redesign devices and platforms through legislation and regulation “is likely to be an uphill battle.” But as she sees it, that battle against freedom of speech must be fought, for the sake of our children and future generations.

One of Bernstein’s stories should have prompted her to reflect on the wisdom of her proposals. When she was growing up in Israel, there was just one TV option: a government-run channel that decolorized its meager offerings lest they prove too alluring. The country’s first few prime ministers, who “disfavored the idea of television generally,” viewed even that concession to popular tastes as a regrettable “compromise.” Frustrated Israelis eventually found a workaround: an “anti-eraser” that recolorized the shows and movies that the government wanted everyone to watch in black and white.

Oddly, Bernstein presents that story to bolster her argument that self-help software is not a satisfactory solution to overuse of social media. “Todo-book replaces Facebook’s newsfeed with a user’s to do list,” she writes. “Instead of scrolling the feed, the user now sees tasks that they planned to do that day, and only when they have finished them does the newsfeed unlock.” Although “Todo-book is a neat idea,” she says, “the question becomes ‘why take this circular route’? Why erase color only to restore it?”

This analogy is doubly puzzling. First, Bernstein is comparing Facebook’s newsfeed, which she thinks makes the platform too appealing, with black-and-white broadcasting, which she thinks made TV less appealing. Second, it was the Israeli government, not a private business, that “erase[d] color,” and it was rebellious viewers, aided by clever entrepreneurs, who “restore[d] it.” There is a lesson there about misguided government meddling, but it is clearly not one that Bernstein has learned.

The post We Don't Need a War on Screen Time appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Freedom’s Dominion: A Saga of White Resistance to Federal Power, by Jefferson Cowie, Basic Books, 512 pages, $35

Jefferson Cowie is a prodigious researcher who often shows sensitivity to historical complexities, and his narrative skills shine. The Vanderbilt historian’s latest book, Freedom’s Dominion, is readable and often provocative. But it superimposes a dubious thesis about Southern history over the facts, arguing that “land dispossession, slavery, power, and oppression do not stand in contrast to freedom—they are expressions of it.”

By Cowie’s account, whites have repeatedly used the doctrine of states’ rights to justify their “freedom to dominate” others. The Southern worldview, he argues, was a doctrine of “racialized radical anti-statism,” which later spread to the North and eventually became normalized in the modern Republican Party.

Central to the book’s narrative is Barbour County, Alabama, and especially its largest community, Eufaula—a place Cowie regards as a microcosm of the white South, and to some extent white America. Whites in both Eufaula and the surrounding county first asserted their “freedom to dominate” by negating treaty guarantees and occupying Creek tribal lands for themselves. In justifying their theft, the culprits, in collusion with Alabama’s leading politicos, cited the sanctity of local control; Cowie calls this a “frenzy of racialized anti-statism.”

In Cowie’s narrative, another alleged freedom—the “freedom to enslave”—animated Barbour County’s campaigns to scuttle both Reconstruction and plans for more equitable land ownership. Once whites had consolidated their power through fraud and violence, they meticulously protected their version of “freedom” through such measures as Jim Crow laws, the convict leasing system, and lynching (“a uniquely sinister form of liberty: the freedom to take a life with impunity”). With the demise of Reconstruction, “freedom proved to be zero-sum: any increase in Black freedom meant a decrease in white freedom,” Cowie writes. “To speak of emancipation today without historicizing and understanding efforts by whites to recapture their freedom to dominate, without seeing how emancipation of African Americans was made into the oppression of whites, is to fail to understand a central problem of American history.”

Throughout the long post-Reconstruction period of “repose on questions of intervention in the South,” whites had little to fear from the federal government. The New Deal failed to challenge, and in some ways reinforced, oppression of African Americans. Cowie argues that President Franklin Roosevelt had to depend on powerful Southern politicians to push through his program, and that they had sufficient clout to blunt anti-lynching bills and other threats to white supremacy.

Post–World War II movements weaved together “racial conservatism and economic conservatism,” which would become “linked to the point of being a single laissez-faire, freedom-loving ideology known simply as conservatism,” Cowie says. “Federal intervention of any kind—whether on lynching, segregation, voting or the regulation of the labor market—constituted a threat upon the sovereignty of a free people.”

The pivotal player in this part of Cowie’s story was Barbour County’s own George C. Wallace, who as governor achieved fame for his invocations of “freedom” and states’ rights, including his infamous 1963 stand in the schoolhouse door at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. In his subsequent presidential campaigns, Cowie writes, Wallace pursued a “Northern strategy” that carried his “racialized anti-statism” to “the blue-collar ethnics” and “the West.” Many of these Wallace voters soon joined “the traditional but right-moving Republican Party,” creating “a political juggernaut.”

Freedom’s Dominion closes with a forceful plea for a new federal mission to “defend the civil and political rights on the local level for all people—cries of freedom to the contrary be damned.”

A major weakness of Cowie’s thesis is its fatal dependence on highly subjective wordplay about the meaning of freedom. Despite some qualifications to the contrary, his book rests on the premise that white rhetoric in some sense corresponded to a coherent and consistent belief system—that lynching, disenfranchisement, genocide, and Jim Crow represented a genuine, albeit twisted, variant of freedom that went beyond mere “ideological window dressing.”

But even if most white Southerners genuinely believed they were champions of “freedom,” that doesn’t make it true, any more than it would be truthful to conclude that Stalinists were legitimately advancing their purported principles of “democracy” and “justice” when they defended the purge trials of the 1930s. Historians have an obligation to question stated assumptions, including those advanced by self-interested whites in Barbour County.

Cowie’s own reporting of salient facts undermines the idea that all that Southern verbiage aligned with a genuine, or remotely coherent, pro-freedom agenda, even one that reserves freedom to members of one race. That pretense was almost routinely cast aside when it conflicted with convenience. As Cowie notes, for example, the whites who dispossessed Creek lands quickly dropped the idea of local control once their actions provoked a war that threatened their very survival: “This time, the states’rights, freedom-loving intruders turned desperately to the federal government to protect them from the problem that they themselves had created.”

A more recent example came in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which overturned racial segregation in public schools. To evade school integration, Eufaula’s city fathers used the federal Housing Act of 1949, a signature accomplishment of President Harry Truman’s Fair Deal, to obliterate an entire black neighborhood through eminent domain. “In the city’s fight against the most important federal intervention in U.S. civil rights history,” Cowie points out, “it armed itself with another wing of federal power.”

While Cowie acknowledges the often negative consequences of New Deal and Fair Deal initiatives for African Americans, such as the use of slum-clearance programs to destroy black neighborhoods, he shows an unfortunate tendency to make excuses for the liberals “who wanted to improve the lives of the poor.” They kept falling victim to “political restrictions,” or were saddled with a “muddled mission,” or were given insufficient “tools and resources for getting the job done.” If the subsequent history of these programs is an indicator, Cowie would do better to ask whether these failures were endemic to the “mission” itself.

Similarly, Cowie is all too willing to give Roosevelt, whom he credits with reading “the politics with horrible clarity,” the benefit of the doubt for failing to press anti-lynching legislation. When weighing the political calculus, Cowie concludes, the president had “too much at stake—social security, collective bargaining, fair labor standards, housing, the Works Progress Administration, rural electrification, banking reform, and a host of other new government programs—to get behind race relations with any vigor.”

Such statements rationalize inaction by a president who, when he wanted something, had a legendary knack for getting it. From 1937 to 1939, lopsided congressional majorities gave Roosevelt more than sufficient political opportunity to both protect the New Deal and push a proposed anti-lynching bill—if an anti-lynching bill was truly a priority. But he never publicly came out in support. In 1940, his influential, conservative, and Southern vice president, John Nance Garner, privately endorsed such a bill. Roosevelt continued to do nothing.

Cowie also wrongly implies that the states’ rights doctrine was unique to the South. He fails to acknowledge, for example, the vigorous assertion of that principle by Northern states in the 1850s through personal liberty laws meant to undermine the Fugitive Slave Act. It is telling that the term states’ rights was almost entirely absent from Southern declarations for secession, which more often centered on a very different, and sometimes dynamically opposed, “compact theory”: The secessionists complained that the federal government had failed to sufficiently enforce the Constitution’s Fugitive Slave Clause. Other revealing indicators of Confederate insincerity and opportunism include the knee-jerk opposition to secessionist movements in West Virginia and in Jones County, Mississippi. Much later, Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus showed his contempt for localism by overriding Little Rock’s decision to integrate its schools.

Cowie knows how to tell a good story. And sometimes he hits the mark; his first chapters, dealing with the expulsion of the Creek, are especially well done. But his book grows weaker as its broader thesis about the meaning and application of freedom becomes ever more forced and untenable.

The post Oppression in the South Was Not an Expression of Freedom appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Here is one version of the left-right spectrum, as described in 1975 by a former Barry Goldwater speechwriter who had left the conservative movement to break bread with Black Panthers and Wobblies. The far right, Karl Hess wrote in Dear America, was the realm of “monarchy, absolute dictatorships, and other forms of absolutely authoritarian rule,” be they fascist or Stalinist or anything else. The left, conversely, favored “the distribution of power into the maximum number of hands.” And the “farthest left you can go, historically at any rate, is anarchism—the total opposition to any institutionalized power.”

Here is an alternate spectrum, presented four years earlier by two members of the John Birch Society. “Communism is, by definition, total government,” Gary Allen and Larry Abraham declared in None Dare Call It Conspiracy. “If you have total government it makes little difference whether you call it Communism, Fascism, Socialism, Caesarism or Pharaohism.” And if “total government (by any of its pseudonyms) stands on the far Left, then by logic the far Right should represent anarchy, or no government.” On the right side of the spectrum, but not as far right as anarchism, was their preferred system: “a Constitutional Republic with a very limited government.”

As you no doubt noticed, these two maps are basically mirror images. Oh, you’ll find little differences if you probe the details. When Hess discussed late Maoist China, for example, he made refinements that the Birchers might discard, distinguishing the party bureaucracy (“much more to the right”) from the rambunctious countryside (“very far to the left”). But both books defined the spectrum in essentially the same terms. They just couldn’t agree on that minor little matter of which way is left and which is right.

Each of those maps has its quirks. When the Bircher duo put anarchy on the far right, they didn’t merely mean free market anarchists of the Murray Rothbard sort: The only anarchist their book mentioned by name was the old-school anarcho-collectivist Mikhail Bakunin, who most people would call a radical leftist. Hess, meanwhile, conceded that his configuration puts the average liberal Democrat “to the right of many conservatives.” Charming as it is for Goldwater’s ex-speechwriter to conclude that his old boss was to the left of Lyndon Johnson, this idea would be a hard sell to most Americans.

But then, every left-right model starts to look strange if you peer closely enough. “Why do we refer to both Milton Friedman (a Jewish, pro-capitalist pacifist) and Adolf Hitler (an anti-Semitic, anti-capitalist militarist) as ‘right wing’ when they had opposite policy views on every point?” ask the historian Hyrum Lewis and his political scientist brother Verlan in The Myth of Left and Right, a new book that sets dynamite charges around the very concept of the political spectrum. “We shouldn’t. Placing both Hitler and Friedman on the same side of a spectrum as if they shared some fundamental essence is both misleading and destructive.”

The Lewises are sometimes prone to overstatement, and one of those overstatements is in that passage: While Friedman did tend to be anti-war, he was not a pacifist. But the most notable war that he supported was World War II, otherwise known as the war against Hitler. Even if the authors got their example slightly wrong, their underlying point about Hitler and Friedman is basically right.

So is their broader point. No model of the political spectrum will ever be satisfying, the Lewis brothers argue, because “left” and “right” are not actually ideologies—they are “bundles of unrelated political positions connected by nothing other than a group.” An American in 2004 who wanted low taxes, a vigorous war on terror, and a constitutional amendment against gay marriage was taking “right-wing” positions, but what linked such disparate opinions? Nothing but sociology, say the Lewises: “A conservative or liberal is not someone who has a conservative or liberal philosophy, but someone who belongs to the conservative or liberal tribe.”

And those tribes’ outlooks evolve over time, as their positions on the issues (and the importance they grant to different issues) gradually change. There are “sticky ideologues” who stay attached to earlier tribal visions, and they’re the people who end up saying things like “I didn’t leave the Democrats—the Democrats left me.” But it’s more common to gradually move along with the crowd. It isn’t the ideology that defines the tribe, the Lewises conclude: It’s the tribe that defines the ideology.

* * *

The left-right framework dates back to the beginning of the French Revolution, when the insurgents sat on the left end of the National Assembly and the royalists on the right. The metaphor soon caught on in much of Europe, but the Lewises argue that it did not really take hold in the U.S. until the 20th century. Some of the earliest American uses they find involve people describing rival factions of socialists. (It is surprisingly common to find references to “right-wing socialists” in newspapers of this period—not because people thought socialists were right-wing, but because some socialists were more radical than others.) Over the course of the 1920s and ’30s, Americans became comfortable describing the left and right wings of the Democratic and Republican parties as well.

There wasn’t much confusion over who belonged on the left or the right in those days, the Lewises claim, because “national politics was primarily about just one issue—the size of government.” By their account, the 1930s spectrum was similar to the one the Birchers imagined in the ’70s, with your position determined by how big and active a state you favor. This is one of their overstatements: Fascism was regularly described as right-wing in the American press of the ’30s, and not just in reference to events in Europe. In 1939, an editorialist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch even expressed wonderment that the fascist intellectual Lawrence Dennis and the socialist economist Paul Sweezy would sound so similar, finding it notable that balanced budgets were under “equal attack from Fascistic and Left-wing economists.”

But it is true that many issues that seem like core left-right concerns today were not treated as such nine decades ago. If you were segregationist but pro–New Deal, you were seen as part of the liberal coalition; if you were pro–civil rights but anti–New Deal, you were called a conservative. Many of the latter insisted that they were “true liberals,” but even then they were not inclined to declare themselves the “true left.” In any event, as more issues attached themselves to the spectrum—desegregation, the Cold War, “family values”—the more complicated the meanings of “left” and “right” became. And then people started projecting their revised spectrums onto the past, tangling everything up further.

The same year Hess published Dear America, the historian Ronald Radosh published Prophets on the Right, a study of five “conservative critics of American globalism” whose views sometimes anticipated those of the anti-militarist New Left: the progressive historian Charles Beard, the muckraking journalist John T. Flynn, the Republican politician Robert Taft, the onetime Nation editor Oswald Garrison Villard, and the aforementioned fascist Lawrence Dennis. It is indeed interesting that these “right-wing” figures criticized U.S. foreign policy in ways that a later “left-wing” historian would find appealing. But what’s even more interesting is that three of the five—Beard, Flynn, and Villard—were seen in the 1930s as men of the left. Their criticisms of Franklin Roosevelt meant they eventually started keeping right-wing company, but only Flynn substantially changed his views in the wake of those new friendships. (On one axis, the Villard of the 1940s was arguably more “left-wing” than the Villard of the 1920s, given that he had retreated from his old laissez faire liberalism and embraced parts of the New Deal.) Even Taft, the standard-bearer of the ’40s and ’50s right, got his start as a progressive Republican. The chief reason he first ran for office in 1920 was to make it easier for local governments to raise taxes.

Here we run into another place where The Myth of Left and Right gets its account slightly wrong in a manner that ultimately underlines rather than undermines its larger themes. When the Lewises discuss the ways people project the spectrum onto past political divisions, they declare it absurd that historians “routinely refer to Jeffersonians as ‘on the left’ and Hamiltonians as ‘on the right'”; they go on to deride the notion that “Jacksonian Democrats share a ‘left-wing’ essence with today’s Democrats and that the Whig Party shares a ‘right-wing’ essence with today’s Republicans.” This feels a few decades out of date. Today one is much more likely to see liberals hailing Hamilton as a hero while offering less love for Jefferson, and Jackson is now widely seen as a prototype for the Trumpian right. But this just supports the Lewis brothers’ point: The meanings of “left” and “right” are so fluid that one generation can flip its fathers’ image of the antebellum spectrum on its head. It’s especially easy when none of the people they’re discussing conceived of their politics in left-right terms.

The Lewises conclude that we’re better off without talk of “left” and “right” at all. They make a compelling case that the metaphor fosters dogmatism, prejudice, confusion, confirmation bias, and a view of politics as a Manichean struggle between two (and only two) forces, among other evils. Better, they say, just to junk it.

* * *

Whether or not you want to throw out the left-right model, you must admit that this would solve one problem: Where do you put the libertarians? The answer isn’t clear unless you build your entire spectrum around the question “How much government should there be?”—and even then, Hess and the Birchers have shown us that there won’t be a complete consensus on where the libertarians should go.

Within the movement, you will sometimes hear references to what sounds like a special political spectrum that’s just for libertarians, with various individuals described as “left-wing” or “right-wing” libertarians. But it soon becomes clear that the speakers don’t always have the same spectrum in mind. You can be a “left-libertarian” by wanting to ally yourself with the Democrats, or by wanting to ally yourself with a radical left that holds Democrats in contempt, or (in a weird twist) by subscribing to an academic philosophy that puts an egalitarian spin on the ideas of John Locke. One can be a “right-libertarian” by being socially conservative but dovish, by being socially liberal but hawkish, by being friendly to corporate interests, or, lately, by being hostile to corporate interests, provided you dress up that opposition with words like “woke capital.” As the larger world’s concepts of “left” and “right” shift, so do those concepts in the liberty movement.

Another new book responds to the “Where do you put the libertarians?” question with an answer that is both simple and complicated: You can put them pretty much everywhere. The Individualists, written by the political philosophers Matt Zwolinski and John Tomasi, is an intellectual history that sets out to show how libertarians can appear alternately as either radical or reactionary. To that end, the authors offer a tour through a kaleidoscopic assortment of libertarian variations, from the pro-border paleolibertarians to the anti-corporate mutualists to the followers of Henry George, with an eye on how different figures and factions have addressed such topics as war, poverty, and civil rights.

The result is one of the best guides you’ll find to the libertarian universe. I have my inevitable disagreements with the authors, but they get two big things right.

For one, they eschew an overly restrictive definition of libertarianism. This is a guide to the things that people who call themselves libertarian believe, not a series of judgments on which of those people actually deserve to be called libertarian. There is a place for such polemics, but there is a place as well for just getting the lay of the land, and this fills that role well. Only toward the end do the authors show their hand and reveal where they are coming from themselves: They are self-described “bleeding-heart libertarians” who are willing to accept some forms of government action in the interest of social justice. But they do not turn the book into a bleeding-heart manifesto, and they generally play fair when presenting their rival schools’ positions.

In place of a narrow definition, Zwolinski and Tomasi present libertarianism as a cluster of commitments: to property rights, negative liberty, individualism, free markets, spontaneous order, and a skepticism toward authority. Different libertarians may stress each commitment to a greater or lesser degree. This is a far more informative model than any one-dimensional line can be. But if you’re attached to that line, it’s not hard to see how leaning more strongly into one principle than another can pull one to the “left” or “right,” whatever those mean this week.

So can how one defines the principle in the first place. If you hear two libertarians proclaiming their support for private property, you shouldn’t assume that they mean the same thing. One might be defending the current distribution of wealth, and the other might be ready to redistribute any property he views as illegitimately acquired. (In 1969, Rothbard suggested that companies that get more than 50 percent of their profits from the government should be turned over to their workers.)

This reflects the second big thing that Zwolinski and Tomasi get right: a well-informed historical sense of how libertarian leanings can manifest themselves in different ways in different times and places. In France and the United Kingdom, they argue, 19th century libertarianism developed “largely in response to the threat of socialism,” and so it often (though not always) took on a conservative cast, marked by alliances with established property owners. “For the first American libertarians,” by contrast, “the greatest enemy to liberty was not socialism but slavery“; the movement’s other targets included patriarchy, corporate privilege, and other foes that today would mark them as “left-wing.” The idea that American libertarianism is “right-wing” didn’t take hold until well after the 20th century was underway.

* * *

Here we come to the book’s biggest misjudgment. To understand what’s wrong with it, you first must be familiar with a common cliché in conversations about how conservatives came to be aligned with libertarians: the idea that this was a “tactical alliance, forged under duress during the Cold War.”

I took that quote from an article in the Claremont Review of Books, but the same basic idea has been expressed in countless other places. And it is plainly false. American libertarians started to ally themselves with conservatives in substantial numbers in the 1930s, well before the Cold War began. Their shared interest wasn’t opposition to communism; it was opposition to the New Deal. The Cold War was, in fact, a major source of tension between conservatives and libertarians, because a great many libertarians thought the Cold War was bad. Over the course of the Soviet-American standoff, conservatives and libertarians locked horns over Vietnam, draft resistance, covert wars, arms control treaties, and more.

If you set aside those groups that simply didn’t deal with foreign policy as a part of their mission, you’ll find that virtually all of the major libertarian institutions that emerged from the ’60s through the ’80s were critics of the Cold War. The Cato Institute and the Mises Institute are often presented as polar opposites, but both were dominated by doves. So was the Libertarian Party. The one major exception was Reason, which was more hawkish in the Soviet era than today—and even so, the magazine’s pages were open to anti–Cold War arguments. Conservative attacks on libertarians in that period were at least as likely to center on foreign policy as they were to center on gay rights or drugs.

Yes, you had Cold Warriors perched at National Review arguing that libertarians should join forces with conservatives (and, in some cases, offering a philosophical rationale for wedding libertarian ideas about freedom to traditionalist views of virtue). But the people who followed that advice tended to be a part of the conservative movement, not the libertarian movement. They didn’t ally themselves; they subsumed themselves. Meanwhile, a vocal minority of libertarians decided to ally instead with the left—thanks, in large part, to that shared opposition to the Cold War. (Noam Chomsky has said that “the only journal I could publish in as long as it existed” was Inquiry, a magazine produced for most of its seven-year history by Cato.) If you polled the movement rank and file on whether they were left-wing or right-wing, the most common response would probably be that they were neither.

It was actually the end of the Cold War that made space for oddities like the “paleo” alliance of the 1990s, precisely because libertarians like Murray Rothbard and conservatives like Pat Buchanan no longer had the question of combating communism to divide them.

Zwolinski and Tomasi know this history. They recognize that the right-libertarian alliance began in the 1930s, not the ’40s or ’50s, and they highlight some of the left-libertarian cooperation of the Cold War era. Yet they christen this period “Cold War libertarianism,” because it was a time when “the struggle against socialism came to dominate the libertarian worldview.” They mean the struggle against socialistic economic policies, yet the name they picked highlights a conflict with a foreign power. It’s an ill-chosen label that inadvertently reinforces a false historical narrative.

That frame also leaves Zwolinski and Tomasi handicapped when describing the world that came after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Having divided the rest of American libertarian history into the anti-authoritarian radicalism of the 19th century and the conservative alliance of the 20th, they describe the period since 1989 as a “third wave” marked by “active contestation”—that is, as a period in which neither radicals nor reactionaries dominate. But is that really so different from the 1970s, when some libertarians happily joined forces with the Reaganites while others celebrated the counterculture, feminism, and humanist psychology? If you subscribed to the Laissez Faire Books catalog in 1975, you could have ordered either Dear America or None Dare Call It Conspiracy. It was a big tent.

* * *

Despite that misstep, The Individualists is an excellent sketch of the libertarian landscape. One of the most impressive things about it is that it manages to show the “left-wing” and “right-wing” sides of libertarianism without lapsing very frequently into the language of “left” and “right.” This is not a book that tries to compress politics into a one-dimensional spectrum. It charts a rich, multidimensional space.

But as you may have noticed, I couldn’t help slipping into that language myself a few times while I discussed the book. The Lewis brothers are right about the left-right spectrum: It’s a misleading metaphor, and we’d be better off if we had never been saddled with it. Yet even if “left” and “right” denote social tribes rather than consistent ideologies, those tribes themselves are real, and this is the language they use to describe themselves.

And I have to confess something: I kind of like all these ridiculous left-right schematics. If you can accept the fact that there is no perfect model of political opinion, just partial and impermanent maps of a vast and constantly shifting territory, then they can be useful snapshots of the terrain. I don’t think either Hess or the Birchers had the one, true diagram of the political world, but each of their approaches is, in its way, an interesting window into 1970s America. If you can comprehend both—and their many rivals too—you can gradually create a cubist portrait of the period that shows more than any single angle would reveal.

In that spirit, let me mention one last take on the left-right spectrum. It was created by the market anarchist Samuel Edward Konkin III, and it appeared in the March 1980 issue of New Libertarian magazine. Like the Hess spectrum and the Bircher spectrum, this one was built around how statist you are. More precisely: Konkin put anarchism on the left and put Actually Existing States on the right, he placed people according to how much he felt they conceded to the latter, and then he collapsed the results into a single Flatland line.

The results resemble that Saul Steinberg cartoon of how the world looks to a New Yorker, where two blocks of the city loom larger than anything on the other side of the Hudson. The left end of the chart is an exhaustive accounting of the libertarian movement as it appeared to Konkin in 1980. (My favorite absurdly specific detail: Reason is to the left of the Libertarian Supper Club of San Diego but to the right of the Libertarian Supper Club of Orange County.) The right end of the chart, on the other hand, feels like a 40-car crash: People with virtually nothing in common politically sit cheek by jowl, to the point where the Palestine Liberation Organization is adjacent to National Review.

And in the center of the Konkin spectrum? There you have the “far-left statists”—that is, people who accepted too much government for the chart maker to consider them libertarians but who came closest to making it into the tent. The furthest left of the far-left statists is our friend Hess, whose tolerance for ultra-local levels of government prompted Konkin to call his views “neighborhood statism.” And four steps to Hess’ right, but still in the far-left-statist zone, there’s the John Birch Society.

As a guide to the politics of 1980, this won’t get you far. But as a glimpse at an eccentric worldview, it’s sublime. Objectively speaking, “left” and “right” are nonsense concepts, for all the reasons Hyrum and Verlan Lewis tell us. Subjectively speaking, people nonetheless use them to make sense of the world. Let there be two, three, many spectrums, each making its own kind of crazy sense.

The post The Left-Right Spectrum Is Mostly Meaningless appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Everything I Need I Get from You: How Fangirls Created the Internet as We Know It is a well-informed, witty, sometimes confessional account of fandom in the age of social media. Part journalism, part history, and part memoir, Kaitlyn Tiffany’s book stretches back to the days before there even was an internet (she dredges up sneering press accounts of bobbysoxers and Beatlemania, including the inevitable moments when reporters couldn’t tell that teens were pulling their legs) and revisits cyberspace’s first colonists (“Before most people were using the internet for anything, fans were using it for everything”). But her focus is on a modern fandom, one she participated in herself: the devotees of the boy band One Direction.

Here she finds a microcosm of everything else online: inscrutable in-jokes, networked power, conspiracy theories, and the human impulse to forge an identity and a community with people who share a passion. This world may feel familiar even to readers who have never stanned a celeb in their lives. “There is no such thing as fan internet,” Tiffany concludes, “because fan internet is the internet.”

The post Review: <i>Everything I Need I Get from You</i> Gives a Fangirl's View of the Internet appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

The Case for Christian Nationalism, by Stephen Wolfe, Canon Press, 488 pages, $24.99

Since the 2016 election, the term Christian nationalism has been used, narrowly, to describe conservative Christian support for Donald Trump and, broadly, to describe any right-wing vision of Christian politics that left-wing observers deplore. This is ironic given the phrase’s history: It began between the world wars with liberal Protestants anxious about the rise of totalitarianism, and it was revived in the 1970s to describe religious anti-colonialism.

We should more properly refer to Christian nationalisms. American history is filled with diverse conceptions of nationhood among religious peoples. Respectable Christian nationalism is often referred to as “civil religion,” as when politicians declare America a shining “city on a hill.” But Christian nationalisms are always contested. The most popular postcard of 1865 pictured the ascent into heaven of the martyred Abraham Lincoln nestled in the bosom of George Washington. Yet until 2019, travelers on Interstate 95 in Virginia could detour to visit the “shrine” of Stonewall Jackson, a slain saint of an opposing, Confederate Christian nationalism.

The Christian nationalist variant getting the most public attention today has a Pentecostal inflection. Journalists cannot resist the spectacle, whether it is self-proclaimed prophet Lance Wallnau peddling $45 “prayer coins” featuring Trump’s face superimposed over that of the Persian King Cyrus, pastor Rafael Cruz promoting Trump as a champion of the “Seven Mountain Mandate,” or televangelist Paula White-Cain praying for “angelic reinforcement” to boost Trump’s reelection.

But another variant has made waves recently with the publication of Stephen Wolfe’s The Case for Christian Nationalism. Wolfe, an evangelical Presbyterian, argues that modern Christians have forgotten the political wisdom of early Protestant reformers and have been lulled into a dangerous secularism. He advocates an ethnically uniform nation ruled by a “Christian prince” with the power to punish blasphemy and false religion.

Wolfe veers chapter by chapter between close readings of often obscure Reformation theologians and mostly unsourced screeds against the dangers of feminist “gynocracy” and immigrant invasion. The book is obtusely argued, poorly written, and worth a read only in the same sense that rubbernecking at a car crash counts as sightseeing. But the ways that Wolfe is wrong are instructive.

For Wolfe, the nationalism part of Christian nationalism is synonymous with ethnicity, which he defines as any self-conscious group of people possessing “the right to be for itself.” Wolfe does not grapple with the vast literature on how ethnicity is socially constructed, preferring instead what he calls a “phenomenological” explanation based on his personal experience and reasoning.

Wolfe’s view of national ethnicity results from his belief in the importance of “particularity,” which he defines as the differences among groups that arise from our “natural inclination to dwell among similar people.” He argues that if something is natural it must be good, because natural things were part of the created order prior to the sinful fall of humanity.

That leads Wolfe to speculate about which human institutions and intuitions are natural and thus good. The category turns out to include civil government, patriarchy, and, bizarrely, hunting. Conveniently, the category of natural things includes whatever Wolfe feels most strongly about. He sacralizes his personal preferences without any reflection on the long history of Christians reading their culturally informed beliefs and practices back into holy writ.

As a result, Wolfe has composed a segregationist political theology. If ethnic differences are the natural order of things and if the natural order is good, he reasons, then those differences should dictate the bounds of an ethnically homogenous Christian nation. Wolfe denies that he is making a white nationalist argument, partly on the grounds that he has nonwhite friends and partly because “the designation ‘white’ is tactically unuseful.” But black friends or not, if you wanted to inject a sacralized white supremacy into the conservative mainstream, this book would be a primer on dog whistling past that particular graveyard.

Other reviewers have highlighted Wolfe’s racist associations. The book’s publisher began as a vanity label for a self-described “paleo-Confederate.” Wolfe co-hosted a politics podcast with a closeted white supremacist named Thomas Achord, who once called black men “chimps.”

But the problem here runs deeper than mere associations. Wolfe repeatedly incorporates notorious white supremacists into his argument, including the neo-Nazi William Gayley Simpson, the antisemite Ernest Renan, and the virulent racist Enoch Powell. His first chapter opens with a quote affirming “tribal behavior” from Samuel Francis, whom the racist writer Jared Taylor once praised as the “premier philosopher of white racial consciousness of our time.” Wolfe’s fascination with such ideas predates this book: He has also written an essay linking Francis’ idea of “anarcho-tyranny” to black people’s allegedly innate criminality.

Fear permeates The Case for Christian Nationalism, especially in Wolfe’s list of 38 aphorisms summarizing his grievances against a changing culture. Not only is feminism assumed to be bad, but we supposedly “live under a gynocracy—a rule by women” who emasculate men by enforcing “feminine virtues, such as empathy, fairness, and equality.” Racism only comes up when Wolfe calls on Christians to ignore accusations of bigotry. And he argues that the future of America depends on keeping children at home into their 20s, growing your own food, weightlifting to keep testosterone levels high, and avoiding vegetable oil.

When fear propels one’s political project, it generates paranoid delusions. It is delusional to propose that the pathway forward for conservative Christians—living in a society in which religious “nones” outnumber any other single religious group—is violent revolution on behalf of a Presbyterian prince who will punish blasphemers. While there are still challenges to religious freedom in America, there has never before been a society in human history where Christians have been so free to worship, speak, and live out their faith.

Karl Deutsch once defined a nation as any “group of people united by a mistaken view about the past and a hatred of their neighbors.” Wolfe’s nativist vision of a Christian nation and his stated aversion to arguing from history fit that definition in both regards. Like a socialist who declares that true communism has never been tried, Wolfe naively asserts the desirability of state-sponsored religion and hardly bothers to prove it ever actually worked.

Wolfe offers a brief apologetic for religious establishment in colonial Massachusetts, gullibly accepting the word of various Puritan leaders that the punishments they meted out to religious dissidents were just and proportionate. But state violence is necessary for any such religio-political project. In Puritan Massachusetts, Quakers risked having their ears cut off and their tongues “bored through with a hot iron,” and they faced execution if they persisted in their blasphemy.

This is the sordid reality of the original “city on a hill.” When Massachusetts Gov. John Winthrop was confronted with what Wolfe might call a “gynocracy”—i.e., women questioning his theology—he responded by digging up Mary Dyer’s stillborn daughter and publishing a pamphlet blaming the baby’s physical deformities on her mother’s heresy. Dyer fled to England and became a Quaker; when she returned to Massachusetts, Winthrop’s successor hanged her. Before the platform dropped, her former pastor called on her to repent to save her life. She replied, “Nay, man, I am not now to repent.” Then asked if she desired the church elders to pray for her soul, she scolded, “I know never an Elder here.” Dyer’s execution is a reminder that Christian nationalism is naturally entangled with state violence.

Religious dissidents were both the beneficiaries and the architects of the decline of religious establishment. When Quakers threw their bodies into the gears of the Puritans’ Christian nationalist machinery, their bravery inspired Roger Williams to leave Massachusetts and found a haven of religious toleration in Rhode Island. A century later, evangelical pastors like Isaac Backus and John Leland fought against religious establishment with pulpit and pen. Yet some of their modern-day descendants have forgotten that, to quote Leland, “these establishments metamorphose the church into a creature…which has a natural tendency to make men conclude that bible religion is nothing but a trick of state.”

Wolfe opens his book with the story of the storming of the Bastille in the French Revolution to illustrate the innate hostility of secularism to religion. But if you ever visit Paris, stop by a little museum on the left bank of the Seine containing the disembodied heads of sculptures depicting the 28 kings of Judah. They decorated Notre Dame Cathedral until a revolutionary mob lopped them off, assuming that they must depict the kings of France. It was not simple secularism that led to this mistaken defacement; it was popular backlash against French Christian nationalism, which had granted its “Christian prince” an absolute, divine right of kings. Secular hostility to religion is learned behavior, a self-fulfilling prophecy rooted in the state’s past attempts to repress religious dissent and coerce a more Christian society.

Wolfe’s ethnicized vision of Christian nationalism is a reminder that, in a post-liberal vacuum, fearful American Christians have become easy targets for people whispering to take up the sword of the state and smite their foes.

The post Beware the 'Christian Prince' appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>