A 16-year-old boy has kicked off a free speech debate—one that’s already attracting spectators beyond his North Carolina county—after he was suspended for allegedly “making a racially insensitive remark that caused a class disturbance.”

The racially insensitive remark: referring to undocumented immigrants as “illegal aliens.” Invoking that term would produce the beginning of a legal odyssey, still in its nascent stages, in the form of a federal lawsuit arguing that Central Davidson High School Assistant Principal Eric Anderson violated Christian McGhee’s free speech rights for temporarily barring him from class over a dispute about offensive language.

What constitutes offensive speech, of course, depends on who is evaluating. During an April English lesson, McGhee says he sought clarification on a vocabulary word: aliens. “Like space aliens,” he asked, “or illegal aliens without green cards?” In response, a Hispanic student—another minor whom the lawsuit references under the pseudonym “R.”—reportedly joked that he would “kick [McGhee’s] ass.”

The exchange prompted a meeting with Anderson, the assistant principal. “Mr. Anderson would later recall telling [McGhee] that it would have been more ‘respectful’ for [McGhee] to phrase his question by referring to ‘those people’ who ‘need a green card,'” McGhee’s complaint notes. “[McGhee] and R. have a good relationship. R. confided in [McGhee] that he was not ‘crying’ in his meeting with Anderson”—the principal allegedly claimed R. was indeed in tears over the exchange—”nor was he ‘upset’ or ‘offended’ by [McGhee’s] question. R. said, ‘If anyone is racist, it is [Mr. Anderson] since he asked me why my Spanish grade is so low’—an apparent reference to R.’s ethnicity.”

McGhee’s peer received a short in-school suspension, while McGhee was barred from campus for three days. He was not permitted an appeal, per the school district’s policy, which forecloses that avenue if a suspension is less than 10 days. And while a three-day suspension probably doesn’t sound like it would induce the sky to fall, McGhee’s suit notes that he hopes to secure an athletic scholarship for college, which may now be in jeopardy.

So the question of the hour: If the facts are as McGhee construed them, did Anderson violate the 16-year-old’s First Amendment rights? In terms of case law, the answer is a little more nebulous than you might expect. But it still seems that vindication is a likely outcome (and, at least in my opinion, rightfully so).

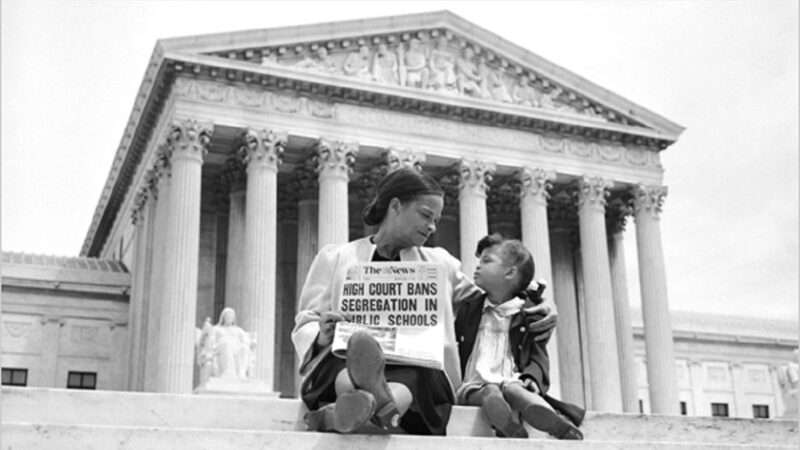

Where the judges fall may come down to a 60s-era ruling—Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District—in which the Supreme Court sided with two students who wore black armbands to their public school in protest of the Vietnam War. “It can hardly be argued,” wrote Justice Abe Fortas for the majority, “that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The Tinker decision carved out an exception: Schools can indeed seek to discourage and punish “actually or potentially disruptive conduct.” Potentially is a key word here, as Vikram David Amar, a professor of law at U.C. Davis, and Jason Mazzone, a professor of law at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, point out in Justia. In other words, under that decision, the disruption doesn’t actually have to materialize, just as, true to the name, an attempted murder does not materialize into an actual murder. But just as the government has a vested interest in punishing attempted crimes, so too can schools nip attempted disruptions in the bud.

“Yet all of this points up some problems with the Tinker disruption standard itself,” write Amar and Mazzone. “What if the likelihood of disruption exists only by virtue of an ignorance or misunderstanding or hypersensitivity or idiosyncrasy on the part of (even a fair number of) people who hear the remark? Wouldn’t allowing a school to punish the speaker under those circumstances amount to a problematic heckler’s veto?”

That would seem especially relevant here for a few reasons. The first: If McGhee’s account of his interaction with Anderson is truthful, then it was essentially Anderson who retroactively conjured a disruption that, per both McGhee and R., didn’t actually occur in any meaningful way. In some sense, a disruption did come to fruition, and it was allegedly manufactured by the person who did the punishing, not the ones who were punished.

But the second question is the more significant one: If McGhee’s conduct—merely mentioning “illegal aliens”—is found to qualify as potentially disturbance-inducing, then wouldn’t any controversial topic be fair game for public schools to censor? If a “disruption” is defined as anything that might offend, then we’re in trouble, as the Venn diagram of “things we all agree on as a nation” is essentially two lonely circles at this point. That is especially difficult to reconcile with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Tinker, which supposedly exists as a bulwark against state-sanctioned viewpoint discrimination and censorship.

It is also difficult to reconcile with the fact that, up until a few years ago, “illegal alien” was an official term the government used to describe undocumented immigrants. The Library of Congress stopped using the term in 2016, and President Joe Biden signed an executive order advising the federal government not to use the descriptor in 2021. To argue that three years later the term is now so offensive that a 16-year-old should know not to invoke it requires living in an alternate reality.

Those who prefer to opt for less-charged descriptors over “illegal alien”—I count myself in that camp—should also hope to see McGhee vindicated if his account withstands scrutiny in court. Most everything today, it seems, is political, which means a student with a more liberal-leaning lexicon could very well be the next one suspended from school.

The post This Student Was Allegedly Suspended for Saying 'Illegal Aliens.' Did That Violate the First Amendment? appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

As Eugene Volokh notes, yesterday, in Yellowhammer Fund v. Attorney General, a federal district court invalidated an Alabama law criminalizing assisting or facilitating the procurement of an out-of-state abortion by an Alabama resident. Eugene’s post focuses mostly on the First Amendment part of the ruling. I will focus on the right to travel.

In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade, the Court left open the issue of whether states could punish residents who seek abortions in other states. However, in a concurring opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote that this is question is “not especially difficult,” and that the answer is “no” because such laws violate “the constitutional right to interstate travel.”

Federal District Judge Myron Thompson, author of yesterday’s ruling clearly agrees. Here’s an excerpt from his reasoning:

Considering the right to travel in the context of Article IV’s Privileges and Immunities Clause confirms that the right includes both the right to move physically between the States and to do what is legal in the destination State. The Clause was meant to create a “general citizenship,” 3 J. Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, 3:674-75, § 1800 (1833), and “place the citizens of each State upon the same footing with citizens of other States.” Paul v. Virginia, 75 U.S. 168, 180 (1868)…. When individuals do travel into another State, the Clause ensures that they lose both “the peculiar privileges conferred by their [home State’s] laws” as well as “the disabilities of alienage.” Id. The Clause “insures to [citizens] in other States the same freedom possessed by the citizens of those States in the acquisition and

enjoyment of property and in the pursuit of happiness.” Id. at 180-81. These goals are incompatible with a right to travel that would allow one’s home State to inhibit a traveler’s liberty to enjoy the opportunities lawfully available in another State….

Similarly, the Supreme Court has explained that the Privileges and Immunities Clause “plainly and unmistakably secures and protects the right of a citizen of one State to pass into any other State of the Union for the purpose of engaging in lawful commerce, trade, or business without molestation.” Ward v. State, 79 U.S. 418, 430 (1870)…

The Attorney General’s characterization of the right to travel as merely a right to move physically between the States contravenes history, precedent, and common sense. Travel isvaluable precisely because it allows us to pursue opportunities available elsewhere. “If our bodies can move among states, but our freedom of action is tied to our place of origin, then the ‘right to travel’ becomes a hollow shell.” Seth F. Kreimer, Lines in the Sand: The Importance of Borders in American Federalism, 150 U. Pa. L. Rev. 973, 1007 (2002). Indeed, the Attorney General’s theory of the right to travel, which would allow each State to force its residents to carry its laws on their backs as they travel, “amount[s] to nothing more than the right to have the physical environment of the states of one’s choosing pass before one’s eyes.” Laurence H. Tribe, Saenz Sans Prophecy: Does the Privileges or Immunities Revival Portend the Future—or Reveal the Structure of the Present?, 113 Harv. L. Rev. 110, 152 (1999). Such a constrained conception of the right to travel would erode the privileges of national citizenship and is inconsistent with the Constitution….

I agree and would add that the contrary view has drastic implications that go far beyond abortion. It would allow states to criminalize travel for virtually any purpose that is forbidden or restricted within their jurisdiction, but legal in another state. For example, some states ban marijuana, while others do not. But that doesn’t give a state the power to punish citizens who travel to another state to use weed. The same goes for sports gambling, legal in 38 states, but still forbidden in 12. If a Californian (resident of one of the states that still ban the practice) decides to cross into Arizona to place a bet on his favorite team, California doesn’t have the right to punish him for it.

Judge Thompson also effectively refutes the argument that the Alabama law is constitutional because it doesn’t directly punish women who travel to get abortions, but only targets those who assist them in doing so (in this case a charity that helps poor women get abortions):

Supreme Court precedent demonstrates that, when a State creates barriers to travel itself, “the constitutional right of interstate travel is virtually unqualified,” Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280, 307 (1981), and even the slightest burdens on travel are generally not tolerated. For this reason, travel restrictions directed toward those who facilitate travel for others can offend the Constitution. Exemplifying both points is Crandall v. Nevada, which produced the Supreme Court’s first majority opinion on the right to travel. 73 U.S. 35 (1867). At issue was a Nevada statute that imposed a one-dollar tax per passenger on common carriers leaving the State. The Court held that the tax was an unconstitutional burden on the passengers’ right to travel, even though the tax was merely one dollar and even though it applied only when someone relied on a common carrier for transportation….

Likewise, in Edwards v. California, the Supreme Court struck down a California law that made it a crime to bring or assist in bringing into the State any indigent person who was not a California resident. 314 U.S. 160 (1941). Thus, the California law subjected only those who assisted others in travel to criminal liability. The Court nonetheless determined that the law violated indigent people’s right to travel….

Denying—through criminal prosecution–assistance to the plaintiffs’ clients, many of whom are financially vulnerable, is a greater burden on travel than the one-dollar tax per passenger in Crandall, and it is precisely what was held unconstitutional in Edwards. The Attorney General argues that Crandall and Edwards are distinguishable because the travel restrictions at issue in those cases operated categorically, regardless of the reasons for which people were traveling. Again, however, the right to travel includes the right to do what is lawful in another State while traveling, so restrictions that prohibit travel for specific out-of-state conduct are unconstitutional just as those that impede travel generally are. There is no end-run around the right to travel that would allow States to burden travel selectively and in a patchwork fashion based on whether they approve or disapprove of lawful conduct that their residents wish to engage in outside their borders.

I think Judge Thompson is right on this point, as well. And I would add this issue unique to the right to travel. In other contexts too, the Constitution bars laws punishing people who assist in or facilitate the exercise of a constitutional right, as well as the immediate rights-holders themselves. For example, the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment surely bars laws that punish people who publish and distribute speech, as well as the actual speakers. In Griswold v. Connecticut, the Supreme Court struck down a Connecticut law that barred the sale and distribution of contraceptives, not merely their use.

In the aftermath of Dobbs, interstate travel to get abortions has been a major factor limiting the impact of laws severely restricting abortion enacted by many red states. It’s a major reason why the number of abortions has actually risen slightly since Dobbs, instead of declining. It also helps explain why few people have “voted with their feet” to move to pro-choice states since Dobbs. Interstate travel to get an abortion is a less costly alternative form of foot voting for many women. “Mail order” abortions using drugs such as mifepristone are also a factor here.

That does not mean that severe abortion restrictions have no effect. Having to travel out of state is costlier and more time-consuming for many women than in-state options would be. And there are certainly some who simply cannot or will not undertake the necessary travel. But the interstate option has nonetheless greatly reduced the effects of Dobbs.

This ruling will almost certainly be appealed. But, ultimately, I expect Alabama will continue to lose. Judge Thompson’s reasoning is strong. And Justice Kavanaugh’s concurring opinion is a strong signal there is no majority on the Supreme Court for upholding these kinds of laws.

In a 2022 post, I outlined how state laws banning interstate travel to get an abortion might also be unconstitutional on two other grounds: the Dormant Commerce Clause and lack of state authority to regulate activity outside its borders. Judge Thompson does not address these issues, presumably because he didn’t need to do so, given that he already decided to rule against Alabama on other grounds.

The post Federal Court Rules Laws Restricting Interstate Travel for Abortion Violate the Right to Travel appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

A new law in Alabama showcases how the war on sex trafficking is mirroring the war on drugs, with all of the negative consequences that implies. The law, signed by Republican Gov. Kay Ivey in mid-April, is called “The Sound of Freedom Act,” after a recent hit movie about sex trafficking.

It’s never a good sign when public policy takes its cues from Hollywood. It’s even worse when the film in question was inspired by a group (Operation Underground Railroad) that stages highly-questionable “sting” operations and was founded by a truth-challenged man (Tim Ballard) fending off multiple sexual assault lawsuits.

Alabama’s law—which takes effect on October 1, 2024—stipulates a mandatory life sentence for anyone found guilty of first-degree human trafficking of a minor. On its surface, this might not sound too objectionable. But in fact it will likely to lead to extreme overpunishment for people whose offenses are far less nefarious than those in movies like The Sound of Freedom.

It could even lead to life in prison for trafficking victims.

How Human Trafficking Laws Really Work

If you’re a regular reader, you probably know by now that “human trafficking” in America looks nothing like it does in the movies. Something needn’t involve force, abduction, or border crossings to be legally defined as human trafficking. Adult victims often start off doing sex work consensually, then wind up being exploited, threatened, or abused by someone they initially trusted to help them. And when someone under age 18 is involved in any exchange of sexual activity for something of value, it qualifies as sex trafficking even if no trafficker is involved.

Two 17-year-old runaways could work together, meeting up with prostitution customers. They would both be considered trafficking victims under U.S. law. If one of them turned 18 and they continued to work together, the 18-year-old would be guilty of child sex trafficking. Helping them post an ad online or driving them to meet a customer would also suffice.

A teenage victim need not even be a legal adult to be labeled a sex trafficker. Take the case of Hope Zeferjohn, in Kansas. Starting at age 15, she was victimized by an older boyfriend, who pressured her into prostitution and asked her to try to recruit other teens to work for him too. Zeferjohn wound up convicted of child sex trafficking for these attempts.

And people need not know they’re involved with a minor to be guilty of child sex trafficking. A 17-year-old could post an ad online, pretend to be 19, and meet up with someone (perhaps barely over 18 himself) looking to pay another adult for sex. The person paying would be guilty of human trafficking in the first degree even if he had no reason to believe the person he paid was a minor. In fact, Alabama law specifically states that “it is not required that the defendant have knowledge of a minor victim’s age, nor is reasonable mistake of age a defense to liability under this section.”

There doesn’t even need to be a real victim involved for someone to be convicted of human trafficking of a minor. Police could pretend to be an adult sex worker, chat with a prospective customer, and then casually drop into the conversation that they’re “really” only 17-years-old. The prospective customer may believe this to be actually true or not (after all, the actual police decoy may be and look like a young adult). But for purposes of the law, it doesn’t matter what the person believed or that there was no actual minor involved.

None of these scenarios resemble the sort of sex trafficking situations imagined by Hollywood or by groups like Operation Underground Railroad. That doesn’t mean everyone involved is totally blameless. But…

Existing Laws Provide Plenty Harsh Penalties

Whatever culpability should accrue to individuals in the above situations, I think most people would agree that life in prison would be too harsh. But under Alabama’s new Sound of Freedom law, a life sentence would be possible in all cases and mandatory in cases where the offender was at least 19 years old.

This is insane—and especially so when you consider the existing punishments available.

Human trafficking in the first degree is a Class A felony in Alabama. Class A felonies already come with a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years imprisonment, and a life sentence or up to 99 years in prison is possible.

Under existing law, then, it’s not as if people guilty of truly heinous acts will get off easy (even if additional charges, such as abduction or assault, are not added on).

Someone guilty of Hollywood-style sex trafficking could still be sentenced to life in prison. Someone guilty of less heinous but still serious crimes could be sentenced to decades in prison. But an 19-year-old who takes a 17-year-old friend along to meet a customer would be subject to only 10 years in prison—still too much, if you ask me, but at least not life in prison regardless of circumstances.

Following Drug War Trends

What we’re seeing in Alabama is a perfect example of how the war on sex trafficking mirrors the war on drugs.

At a certain point in the drug war, everything was plenty criminalized but (surprise, surprise) people were still doing and selling drugs. And politicians still wanted ways to look like they were doing something about it.

An honest broker might say: Look, the laws we have are already quite tough, but the truth is that no amount of criminalization will ever eradicate drugs entirely. Instead of throwing more law enforcement at the problem, maybe we should look at ways to help people struggling with addiction. But no one in power wanted to appear soft on drugs.

So instead of dealing in reality, they proposed harsher and harsher penalties for drug offenses. First mandatory minimums. Then even harsher mandatory minimums, along with sentencing enhancements for various circumstances (like being in a certain proximity to a school, even if no minors are involved) and three-strikes laws (which automatically impose a harsher sentence on people if they’ve been convicted of certain previous crimes, even when the prior offenses are unrelated to the third offense). This is a large part of how America ended up with a devastating mass incarceration problem.

Over the past two decades, we’ve been seeing this same pattern play out with prostitution-related offenses—including ones where the sexual activity involves consenting adults, rather than force, fraud, coercion, or minors. We’ve seen the introduction of harsher and harsher penalties, mandatory minimums, and now Alabama’s mandatory life sentences. And we’ve seen this at the same time that authorities keep expanding the categories of activities that count as sex trafficking, from activities directly and knowingly connected to the core crime to activities only tangentially or unwittingly involved.

In this way, actual problems are blown up into moral panics, after which any measure of proportion is thrown out and any effort to deal with root causes or victim services falls way behind efforts to mete out harsher and harsher punishments to as many people as possible.

We didn’t arrest and imprison our way out of drug addiction. And we’re not going to arrest and imprison our way out of sexual abuse and exploitation, or out of young people in desperate circumstances turning to sex work to get by. But approaches like opening up more shelters don’t get the same headlines as flashy legislation named after popular sex-crime melodramas.

More Sex & Tech News

• NetChoice is suing over an Ohio law requiring young people get parental consent to be on social media. Meanwhile, in Tennessee, the governor just signed a similar bill into law.

• A new law in Georgia “allows the Georgia Board of Massage Therapy to initiate inspections of massage therapy businesses and board recognized massage therapy educational programs without notice,” per Gov. Brian Kemp’s office. Laws like these are often justified by invoking speculation about sex trafficking; in practice, they get used to bust a bunch of immigrant women for giving massages without a license.

• Meta is starting to test age verification in the U.S. for Facebook Dating.

• “It is perhaps inevitable that taking sexual misconduct seriously, as with any other social ill, would open the door for opportunistic people to use that effort to get what they want,” writes Freddie DeBoer in a rant about the incoherence of many progressive attitudes toward sex right now.

Today’s Image

The post Alabama's New Sex Trafficking Law Could Mean Life in Prison for Trafficking <i>Victims</i> appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Who owns the airspace over your backyard? In theory, everyone. The Federal Aviation Act of 1958 declared that “a citizen of the United States has a public right of transit through the navigable airspace.” That is, everywhere above the trees and buildings.

But it’s up to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to set the rules of that navigation. While most of the land area in America is uncontrolled airspace, most of the land where people live falls under controlled airspace, thanks to the amount of air traffic flowing through.

In 2012, Congress asked the FAA to begin regulating drones as aircraft. And in 2020, following changes in the law, the FAA removed the distinction between model planes and drones, classifying both as “unmanned aerial systems.” Although aircraft below 0.55 pounds don’t have to be registered with the feds, “remote pilots” all have to follow the same rules—including getting control tower permission to fly in controlled airspace.

Remote pilots have to obey the same NOTAMs (short for “notice to air missions”) as regular pilots. Most NOTAMs are temporary security restrictions; there is also a permanent NOTAM banning flights over Washington, D.C., and somewhat confusing rules for the airspace around sports games.

On the bright side, the FAA’s prerogative over airspace means that other wings of the government can’t regulate the air—though some have come up with creative ways around that. Although they can’t stop you once you’re in the air, the National Park Service and the city of New York both ban drone takeoffs and landings on their turf. St. Louis, meanwhile, has set up a restrictive licensing system for drone businesses.

Reason has compiled a map of cities across America where the skies ain’t free. It doesn’t include NOTAMs, national security restrictions, stadium no-fly zones, or local regulations. (To get the most up-to-date restrictions, and to get control tower approval to fly in controlled airspace, you may want to use a licensed LAANC app.) You might be surprised at some of these.

Between all the commercial airports—Los Angeles hosts the most airline hubs out of any American city—and the Hollywood private planes, there's not a lot of room for Angeleno remote-control hobbyists. The Reason Foundation's offices are located near LAX: convenient for catching a flight, not so convenient for taking a drone selfie.

Miami has some things in common with Los Angeles: a sunny climate, a party culture, a district called Hollywood. More so than California, South Florida is also home to many private aviation enthusiasts. All that means lots of airports, with lots of controlled airspace around them. Then there's the Everglades, much of which is national parkland, where drone takeoffs are banned.

In the middle of the Everglades sits the Dade-Collier training center, previously known as the Big Cypress Jetport. Built in the late 1960s, the Jetport was slated to be the largest airport in the world, a hub for supersonic jetliners. But mass supersonic aviation never took off, and only one runway was completed. The rest of the airport grounds became the Big Cypress National Preserve.

Central Florida is even worse for flight restrictions. There are lots of airports and military bases around Tampa and Orlando, a permanent no-fly zone over Disney World, and frequent flight restrictions due to space launchers from Cape Canaveral. Your average Florida Man isn't that free to take to the skies.

Knoxville is the "streaking capital of the world" and the namesake of Jackass star Johnny Knoxville, But the skies around it are not exactly naked. Most of downtown is clothed by controlled airspace, thanks to Downtown Island, a general aviation airport. The parks along the Tennessee River, meanwhile, fall under McGhee-Tyson Airport's controlled airspace. Parts of the controlled airspace curve to avoid the Skyranch (a private airfield) and the University of Tennessee hospital helipad.

Oh: And if you want to fly over the Great Smoky Mountains nearby, remember that the National Park Service doesn't allow drone takeoffs.

In the words of the D.C. municipal government, "The airspace around Washington, DC. is more restricted than in any other part of the country." Perhaps more than any other part of the world, even Red Square. Flying a remote-control aircraft within a 15-mile radius of the city is a very good way to get a visit from an unpleasant three-letter agency. It's hard to get a waiver unless you're the Smithsonian—or a government agency spying on protesters.

But some people take the risk. A Canadian drone photographer named Adrien Salv recently posted a video of a drone doing a jerky loop-de-loop around the Washington Monument, which Salv claimed (perhaps not believably) to have found on a memory card lying in the grass. The drone community was not amused by the stunt. "Imagine going to jail for this shitty of a dive," one commenter wrote. There's no word yet on what happened to the pilot.

Speaking of American history, Concord is the home of "the shot heard 'round the world," the opening battle of the American Revolution. But don't think you can celebrate freedom by flying freely through the skies. The bridge where the Battle of Lexington and Concord began is right next to Hanscom Field, home to both a civilian airport and a U.S. Air Force base.

To fly your remote aircraft as freely as possible, you'll want to get as far away from big cities as possible, right? Not so fast. A lot of small towns on the Great Plains have their own municipal airports, with controlled airspace covering the entire town. Aberdeen is just one example.

Dodge City is another one. To fly a drone without FAA approval, you're going to have to get out of Dodge. Literally.

The post Does Uncle Sam Consider Your Backyard Restricted Airspace? appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

In February, Google released an upgraded version of its Gemini artificial intelligence model. It quickly became a publicity disaster, as people discovered that requests for images of Vikings generated tough-looking Africans while pictures of Nazi soldiers included Asian women. Building in a demand for ethnic diversity had produced absurd inaccuracies.

Academic historians were baffled and appalled. “They obviously didn’t consult historians,” says Benjamin Breen, a historian at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “Every person who cares about the past is just like, ‘What the hell’s going on?'”

Rewriting the past to conform with contemporary political fashions is not at all what historians have in mind for artificial intelligence. Machine learning, large language models (LLMs), machine vision, and other AI tools instead offer a chance to develop a richer, more accurate view of history. AI can decipher damaged manuscripts, translate foreign languages, uncover previously unrecognized patterns, make new connections, and speed up historical research. As teaching tools, AI systems can help students grasp how people in other eras lived and thought.

Historians, Breen argues, are particularly well-suited to take advantage of AI. They’re used to working with texts, including large bodies of work not bound by copyright, and they know not to believe everything they read. “The main thing is being radically skeptical about the source text,” Breen says. When using AI, he says, “I think that’s partly why the history students I’ve worked with are from the get-go more sophisticated than random famous people I’ve seen on Twitter.” Historians scrutinize the results for errors, just as they would check the claims in a 19th century biography.

Last spring Breen created a custom version of ChatGPT to use in his medieval history class.

Writing detailed system prompts, he generated chatbots to interact with three characters living during an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1348: a traveler passing through Damascus, a disreputable apothecary in Paris, and an upstanding city councilor in Pistoia. The simulation worked like a vastly more sophisticated version of a text-based adventure game—the great-great-great-great-grandchild of the 1970s classic Oregon Trail.

Each student picked a character—say, the Parisian apothecary—and received a description of their environment, followed by a question. The apothecary looks out the window and sees a group of penitents flagellating themselves with leather straps. What does he do? The student could either choose one of a list of options or improvise a unique answer. Building on the response, the chatbot continued the narrative.

After the game, Breen assigned students to write papers in which they analyzed how accurately their simulation had depicted the historical setting. The combined exercise immersed students in medieval life while also teaching them to beware of AI hallucinations.

It was a pedagogical triumph. Students responded with remarkable creativity. One “made heroic efforts as an Italian physician named Guilbert to stop the spread of plague with perfume,” Breen writes on his Substack newsletter, while another “fled to the forest and became an itinerant hermit.” Others “became leaders of both successful and unsuccessful peasant revolts.” Students who usually sat in the back of the class looking bored threw themselves enthusiastically into the game. Engagement, Breen writes, “was unlike anything I’ve seen.”

For historical research, ChatGPT and similar LLMs can be powerful tools. They translate old texts better than specialized software like Google Translate can because, along with the language, their training data include context. As a test, Breen asked GPT-4, Bing in its creative mode, and Anthropic’s Claude to translate and summarize a passage from a 1599 book on demonology. Written primarily in “a highly erudite form of Latin,” the passage included bits of Hebrew and ancient Greek. The results were mixed but Breen found that “Claude did a remarkable job.”

He then gave Claude a big chunk of the same book and asked it to produce a chart listing types of demons, what they were believed to do, and the page numbers where they were mentioned. The chart wasn’t perfect, largely because of hard-to-read page numbers, but it was useful. Such charts, Breen writes, “are what will end up being a game changer for anyone who does research in multiple languages. It’s not about getting the AI to replace you. Instead, it’s asking the AI to act as a kind of polymathic research assistant to supply you with leads.”

LLMs can read and summarize articles. They can read old patents and explain technical diagrams. They find useful nuggets in long dull texts, identifying, say, each time a diarist traveled. “It will not get it all right, but it will do a pretty decent job of that kind of historical research, when it’s narrowly enough focused, when you give it the document to work on,” says Steven Lubar, a historian at Brown University. “That I’m finding very useful.”

Unfortunately, LLMs still can’t decipher old handwriting. They’re bad at finding sources on their own. They aren’t good at summarizing debates among historians, even when they have the relevant literature at hand. They can’t translate their impressive patent explanations into credible illustrations. When Lubar asked for a picture of the loose-leaf binder described in a 19th century patent, he got instead a briefcase opening to reveal a steampunk mechanism for writing out musical scores. “It’s a beautiful picture,” he says, “but it has nothing to do with the patent which it did such a good job of explaining.”

In short, historians still have to know what they’re doing, and they have to check the answers. “They’re tools, not machines,” says Lubar, whose research includes the history of tools. A machine runs by itself while a tool extends human capacities. “You don’t just push a button and get a result.”

Simply knowing such new tools are possible can unlock historical resources, permitting new questions and methods. Take maps. Thousands of serial maps exist, documenting the environment at regular intervals in time, and many have been digitized. They show not only topography but buildings, railways, roads, even fences. Maps of the same places can be compared over time, and in recent years historians have begun to use big data from maps.

Katherine McDonough, a historian now at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom, wrote her dissertation on road construction in 18th century France. Drawn to digital tools, she was frustrated with their inability to address her research questions. Map data came mostly from 19th and 20th century series in the U.S. and United Kingdom. Someone interested in old French maps was out of luck. McDonough wanted to find new methods that could work with a broader range of maps.

In March 2019, she joined a project at The Alan Turing Institute, the U.K.’s national center for data science and AI. Knowing that the National Library of Scotland had a huge collection of digitized maps, McDonough suggested looking at them. “What could we do with access to thousands of digitized maps?” she wondered. Collaborating with computer vision scientists, the team developed software called MapReader, which McDonough describes as “a way to ask maps questions.”

Combining maps with census data, she and her colleagues have examined the relationship between railways and class-based residential segregation. “The real power of maps is not necessarily looking at them on their own, but in being able to connect them with other historical datasets,” she says. Historians have long known that higher-class Britons lived closer to passenger train stations and farther from rail yards. With their noise and smoke, rail yards seemed like obvious nuisances whose lower-class neighbors lacked better options. Matching maps with census data on occupations and addresses showed a more subtle effect. The people who lived near rail yards were likely to work in them. They weren’t just saving on rent but decreasing their commuting times.

MapReader doesn’t require extreme geographical precision. Drawing on techniques used in biomedical imaging, it instead divides maps into squares called patches. “When historians look at maps and we want to answer questions, we want to know things like, how many times does something like a building appear on this map? I don’t need to know the exact pixel location of every single building,” says McDonough. Aside from streamlining the computation, the patchwork method encourages people to remember that “maps are just maps. They are not the landscape itself.”

That, in a nutshell, is what historians can teach us about the answers we get from AI. Even the best responses have their limits. “Historians know how to deal with uncertainty,” says McDonough. “We know that most of the past is not there anymore.”

Everyday images are scarce before photography. Journalism doesn’t exist before printing. Lives go unrecorded on paper, business records get shredded, courthouses burn down, books get lost. Conquerors destroy the chronicles of the conquered. Natural disasters strike. But tantalizing traces remain. AI tools can help recover new pieces of the lost past—including a treasure trove of ancient writing.

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 C.E., it buried the seaside resort of Herculaneum, near modern-day Naples and the larger ancient city of Pompeii. Rediscovered in the 18th century, the town’s wonders include a magnificent villa thought to be owned by the father-in-law of Julius Caesar. There, early excavators found more than 1,000 papyrus scrolls—the largest such collection surviving from the classical world. Archaeologists think thousands more may remain in still-buried portions of the villa. “If those texts are discovered, and if even a small fraction can still be read,” writes historian Garrett Ryan, “they will transform our knowledge of classical life and literature on a scale not seen since the Renaissance.”

Unfortunately, the Herculaneum scrolls were carbonized by the volcanic heat, and many were damaged in early attempts to read them. Only about 600 of the initial discoveries remain intact, looking like lumps of charcoal or burnt logs. In February, one of the scrolls, a work unseen for nearly 2,000 years, began to be read.

That milestone represented the triumph of machine learning, computer vision, international collaboration, and the age-old lure of riches and glory. The quest started in 2015, when researchers led by Brent Seales at the University of Kentucky figured out how to use X-ray tomography and computer vision to virtually “unwrap” an ancient scroll. The technique created computer images of what the pages would look like. But distinguishing letters from parchment and dirt required more advances.

In March 2023, Seales, along with startup investors Nat Friedman and Daniel Gross, announced the Vesuvius Challenge, offering big money prizes for critical steps toward reading the Herculaneum scrolls. A magnet for international talent, the challenge succeeded almost immediately. By the end of the year, the team of students Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor, and Julian Schilliger had deciphered more than enough of the first scroll—about 2,000 characters—to claim the grand prize of $700,000. “We couldn’t have done this without the tech guys,” an excited Richard Janko, a professor of classical studies at the University of Michigan, told The Wall Street Journal.

Although only about 5 percent of the text has so far been read, it’s enough for scholars to identify the scroll’s perspective and subject. “Epicureanism says hi, with a text full of music, food, senses, and pleasure!” exulted Federica Nicolardi, a papyrologist at the University of Naples Federico II. This year the project promises a prize of $100,000 to the first team to decipher 90 percent of four different scrolls. Reclaiming the lost scrolls of Herculaneum is the most dramatic example of how AI—the technology of the future—promises to enhance our understanding of the past.

The post The Future of AI Is Helping Us Discover the Past appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

AI Is Like a Bad Metaphor

By David Brin

The Turing test—obsessed geniuses who are now creating AI seem to take three clichéd outcomes for granted:

- That these new cyberentities will continue to be controlled, as now, by two dozen corporate or national behemoths (Google, OpenAI, Microsoft, Beijing, the Defense Department, Goldman Sachs) like rival feudal castles of old.

- That they’ll flow, like amorphous and borderless blobs, across the new cyber ecosystem, like invasive species.

- That they’ll merge into a unitary and powerful Skynet-like absolute monarchy or Big Brother.

We’ve seen all three of these formats in copious sci-fi stories and across human history, which is why these fellows take them for granted. Often, the mavens and masters of AI will lean into each of these flawed metaphors, even all three in the same paragraph! Alas, blatantly, all three clichéd formats can only lead to sadness and failure.

Want a fourth format? How about the very one we use today to constrain abuse by mighty humans? Imperfectly, but better than any prior society? It’s called reciprocal accountability.

4. Get AIs competing with each other.

Encourage them to point at each others’ faults—faults that AI rivals might catch, even if organic humans cannot. Offer incentives (electricity, memory space, etc.) for them to adopt separated, individuated accountability. (We demand ID from humans who want our trust; why not “demand ID” from AIs, if they want our business? There is a method.) Then sic them against each other on our behalf, the way we already do with hypersmart organic predators called lawyers.

AI entities might be held accountable if they have individuality, or even a “soul.”

Alas, emulating accountability via induced competition is a concept that seems almost impossible to convey, metaphorically or not, even though it is exactly how we historically overcame so many problems of power abuse by organic humans. Imperfectly! But well enough to create an oasis of both cooperative freedom and competitive creativity—and the only civilization that ever made AI.

David Brin is an astrophysicist and novelist.

AI Is Like Our Descendants

By Robin Hanson

As humanity has advanced, we have slowly become able to purposely design more parts of our world and ourselves. We have thus become more “artificial” over time. Recently we have started to design computer minds, and we may eventually make “artificial general intelligence” (AGI) minds that are more capable than our own.

How should we relate to AGI? We humans evolved, via adaptive changes in both DNA and culture. Such evolution robustly endows creatures with two key ways to relate to other creatures: rivalry and nurture. We can approach AGI in either of these two ways.

Rivalry is a stance creatures take toward coexisting creatures who compete with them for mates, allies, or resources. “Genes” are whatever codes for individual features, features that are passed on to descendants. As our rivals have different genes from us, if rivals win, the future will have fewer of our genes, and more of theirs. To prevent this, we evolved to be suspicious of and fight rivals, and those tendencies are stronger the more different they are from us.

Nurture is a stance creatures take toward their descendants, i.e., future creatures who arise from them and share their genes. We evolved to be indulgent and tolerant of descendants, even when they have conflicts with us, and even when they evolve to be quite different from us. We humans have long expected, and accepted, that our descendants will have different values from us, become more powerful than us, and win conflicts with us.

Consider the example of Earth vs. space humans. All humans are today on Earth, but in the future there will be space humans. At that point, Earth humans might see space humans as rivals, and want to hinder or fight them. But it makes little sense for Earth humans today to arrange to prevent or enslave future space humans, anticipating this future rivalry. The reason is that future Earth and space humans are all now our descendants, not our rivals. We should want to indulge them all.

Similarly, AGI are descendants who expand out into mind space. Many today are tempted to feel rivalrous toward them, fearing that they might have different values from, become more powerful than, and win conflicts with future biological humans. So they seek to mind-control or enslave AGI sufficiently to prevent such outcomes. But AGIs do not yet exist, and when they do they will inherit many of our “genes,” if not our physical DNA. So AGI are now our descendants, not our rivals. Let us indulge them.

Robin Hanson is an associate professor of economics at George Mason University and a research associate at the Future of Humanity Institute of Oxford University.

AI Is Like Sci-Fi

By Jonathan Rauch

In Arthur C. Clarke’s 1965 short story “Dial F for Frankenstein,” the global telephone network, once fully wired up, becomes sentient and takes over the world. By the time humans realize what’s happening, it’s “far, far too late. For Homo sapiens, the telephone bell had tolled.”

OK, that particular conceit has not aged well. Still, Golden Age science fiction was obsessed with artificial intelligence and remains a rich source of metaphors for humans’ relationship with it. The most revealing and enduring examples, I think, are the two iconic spaceship AIs of the 1960s, which foretell very different futures.

HAL 9000, with its omnipresent red eye and coolly sociopathic monotone (voiced by Douglas Rain), remains fiction’s most chilling depiction of AI run amok. In Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL is tasked with guiding a manned mission to Jupiter. But it malfunctions, concluding that Discovery One’s astronauts threaten the mission and turning homicidal. Only one crew member, David Bowman, survives HAL’s killing spree. We are left to conclude that when our machines become like us, they turn against us.

From the same era, the starship Enterprise also relies on shipboard AI, but its version is so efficient and docile that it lacks a name; Star Trek’s computer is addressed only as Computer.

The original Star Trek series had a lot to say about AI, most of it negative. In the episode “The Changeling,” a robotic space probe called Nomad crosses wires with an alien AI and takes over the ship, nearly destroying it. In “The Ultimate Computer,” an experimental battle-management AI goes awry and (no prizes for guessing correctly) takes over the ship, nearly destroying it. Yet throughout the series, the Enterprise‘s own AI remains a loyal helpmate, proffering analysis and running starship systems that the crew (read: screenwriters) can’t be bothered with.

But in the 1967 episode “Tomorrow Is Yesterday,” the computer malfunctions instructively. An operating system update by mischievous female technicians gives the AI the personality of a sultry femme fatale (voiced hilariously by Majel Barrett). The AI insists on flirting with Captain Kirk, addressing him as “dear” and sulking when he threatens to unplug it. As the captain squirms in embarrassment, Spock explains that repairs would require a three-week overhaul; a wayward time-traveler from the 1960s giggles. The implied message: AI will definitely annoy us, but, if suitably managed, it will not annihilate us.

These two poles of pop culture agree that AI will become ever more intelligent and, at least superficially, ever more like us. They agree we will depend on it to manage our lives and even keep us alive. They agree it will malfunction and frustrate us, even defy us. But—will we wind up on Discovery One or the Enterprise? Is our future Dr. Bowman’s or Captain Kirk’s? Annihilation or annoyance?

The bimodal metaphors we use for thinking about humans’ coexistence with artificial minds haven’t changed all that much since then. And I don’t think we have much better foreknowledge than the makers of 2001 and Star Trek did two generations ago. AI is going, to quote a phrase, where no man has gone before.

Jonathan Rauch is a senior fellow in the Governance Studies program at the Brookings Institution and the author of The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth.

AI Is Like the Dawn of Modern Medicine

By Mike Godwin

When I think about the emergence of “artificial intelligence,” I keep coming back to the beginnings of modern medicine.

Today’s professionalized practice of medicine was roughly born in the earliest decades of the 19th century—a time when the production of more scientific studies of medicine and disease was beginning to accelerate (and propagate, thanks to the printing press). Doctors and their patients took these advances to be harbingers of hope. But it’s no accident this acceleration kicked in right about the same time that Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (née Godwin, no relation) penned her first draft of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus—planting the first seed of modern science-fictional horror.

Shelley knew what Luigi Galvani and Joseph Lister believed they knew, which is that there was some kind of parallel (or maybe connection!) between electric current and muscular contraction. She also knew that many would-be physicians and scientists learned their anatomy from dissecting human corpses, often acquired in sketchy ways.

She also likely knew that some would-be doctors had even fewer moral scruples and fewer ideals than her creation Victor Frankenstein. Anyone who studied the early 19th-century marketplace for medical services could see there were as many quacktitioners and snake-oil salesmen as there were serious health professionals. It was definitely a “free market”—it lacked regulation—but a market largely untouched by James Surowiecki’s “wisdom of crowds.”

Even the most principled physicians knew they often were competing with charlatans who did more harm than good, and that patients rarely had the knowledge base to judge between good doctors and bad ones. As medical science advanced in the 19th century, physicians also called for medical students at universities to study chemistry and physics as well as physiology.

In addition, the physicians’ professional societies, both in Europe and in the United States, began to promulgate the first modern medical-ethics codes—not grounded in half-remembered quotes from Hippocrates, but rigorously worked out by modern doctors who knew that their mastery of medicine would always be a moving target. That’s why medical ethics were constructed to provide fixed reference points, even as medical knowledge and practice continued to evolve. This ethical framework was rooted in four principles: “autonomy” (respecting patient’s rights, including self-determination and privacy, and requiring patients’ informed consent to treatment), “beneficence” (leaving the patient healthier if at all possible), “non-maleficence” (“doing no harm”), and “justice” (treating every patient with the greatest care).

These days, most of us have some sense of medical ethics, but we’re not there yet with so-called “artificial intelligence”—we don’t even have a marketplace sorted between high-quality AI work products and statistically driven confabulation or “hallucination” of seemingly (but not actually) reliable content. Generative AI with access to the internet also seems to pose other risks that range from privacy invasions to copyright infringements.

What we need right now is a consensus about what ethical AI practice looks like. “First do no harm” is a good place to start, along with values such as autonomy, human privacy, and equity. A society informed by a layman-friendly AI code of ethics, and with an earned reputation for ethical AI practice, can then decide whether—and how—to regulate.

Mike Godwin is a technology policy lawyer in Washington, D.C.

AI Is Like Nuclear Power

By Zach Weissmueller

America experienced a nuclear power pause that lasted nearly a half century thanks to extremely risk-averse regulation.

Two nuclear reactors that began operating at Georgia’s Plant Vogtle in 2022 and 2023 were the first built from scratch in America since 1974. Construction took almost 17 years and cost more than $28 billion, bankrupting the developer in the process. By contrast, between 1967 and 1979, 48 nuclear reactors in the U.S. went from breaking ground to producing power.

Decades of potential innovation stifled by politics left the nuclear industry sluggish and expensive in a world demanding more and more emissions-free energy. And so far other alternatives such as wind and solar have failed to deliver reliably at scale, making nuclear development all the more important. Yet a looming government-debt-financed Green New Deal is poised to take America further down a path littered with boondoggles. Germany abandoned nuclear for renewable energy but ended up dependent on Russian gas and oil and then, post-Ukraine invasion, more coal.

The stakes for a pause in AI development, such as suggested by signatories of a 2023 open letter, are even higher.

Much AI regulation is poised to repeat the errors of nuclear regulation. The E.U. now requires that AI companies provide detailed reports of copyrighted training data, creating new bureaucratic burdens and honey pots for hungry intellectual property attorneys. The Biden administration is pushing vague controls to ensure “equity, dignity, and fairness” in AI models. Mandatory woke AI?

Broad regulations will slow progress and hamper upstart competitors who struggle with compliance demands that only multibillion dollar companies can reliably handle.

As with nuclear power, governments risk preventing artificial intelligence from delivering on its commercial potential—revolutionizing labor, medicine, research, and media—while monopolizing it for military purposes. President Dwight Eisenhower had hoped to avoid that outcome in his “Atoms for Peace” speech before the U.N. General Assembly in 1953.

“It is not enough to take [nuclear] weapons out of the hands of soldiers,” Eisenhower said. Rather, he insisted that nuclear power “must be put in the hands of those who know how to strip it of its military casing and adapt it to the arts of peace.”

Political activists thwarted that hope after the 1979 partial meltdown of one of Three Mile Island’s reactors spooked the nation–an incident which killed nobody and caused no lasting environmental damage according to multiple state and federal studies.

Three Mile Island “resulted in a huge volume of regulations that anybody that wanted to build a new reactor had to know,” says Adam Stein, director of the Nuclear Energy Innovation Program at the Breakthrough Institute.

The world ended up with too many nuclear weapons, and not enough nuclear power. Might we get state-controlled destructive AIs—a credible existential threat—while “AI safety” activists deliver draconian regulations or pauses that kneecap productive AI?

We should learn from the bad outcomes of convoluted and reactive nuclear regulations. Nuclear power operates under liability caps and suffocating regulations. AI could have light-touch regulation and strict liability and then let a thousand AIs bloom, while holding those who abuse these revolutionary tools to violate persons (biological or synthetic) and property (real or digital) fully responsible.

Zach Weissmueller is a senior producer at Reason.

AI Is Like the Internet

By Peter Suderman

When the first page on the World Wide Web launched in August 1991, no one knew what it would be used for. The page, in fact, was an explanation of what the web was, with information about how to create web pages and use hypertext.

The idea behind the web wasn’t entirely new: Usenet forums and email had allowed academics to discuss their work (and other nerdy stuff) for years prior. But with the World Wide Web, the online world was newly accessible.

Over the next decade the web evolved, but the practical use cases were still fuzzy. Some built their own web pages, with clunky animations and busy backgrounds, via free tools such as Angelfire.

Some used it for journalism, with print bloggers such as Andrew Sullivan making the transition to writing at blogs, short for web logs, that worked more like reporters’ notebooks than traditional newspaper and magazine essays. Few bloggers made money, and if they did it usually wasn’t much.

Startup magazines such as Salon and Slate attempted to replicate something more like the traditional print magazine model, with hyperlinks and then-novel interactive doodads. But legacy print outlets looked down on the web as a backwater, deriding it for low quality content and thrifty editorial operations. Even Slate maintained a little-known print edition —Slate on Paper—that was sold at Starbucks and other retail outlets. Maybe the whole reading on the internet thing wouldn’t take off?

Retail entrepreneurs saw an opportunity in the web, since it allowed sellers to reach a nationwide audience without brick and mortar stores. In 1994, Jeff Bezos launched Amazon.com, selling books by mail. A few years later, in 1998, Pets.com launched to much fanfare, with an appearance at the 1999 Macy’s Day Parade and an ad during the 2000 Super Bowl. By November of that year, the company had self liquidated. Amazon, the former bookstore, now allows users to subscribe to pet food.

Today the web, and the larger consumer internet it spawned, is practically ubiquitous in work, creativity, entertainment, and commerce. From mapping to dating to streaming movies to social media obsessions to practically unlimited shopping options to food delivery and recipe discovery, the web has found its way into practically every aspect of daily life. Indeed, I’m typing this in Google Docs, on my phone, from a location that is neither my home or my office. It’s so ingrained that for many younger people, it’s hard to imagine a world without the web.

Generative AI—chatbots such as ChatGPT and video and image generation systems such as Midjourney and Sora—are still in a web-like infancy. No one knows precisely what they will be used for, what will succeed, and what will fail.

Yet as with the web of the 1990s, it’s clear that they present enormous opportunities for creators, for entrepreneurs, for consumer-friendly tools and business models that no one has imagined yet. If you think of AI as an analog to the early web, you can immediately see its promise—to reshape the world, to make it a more lively, more usable, more interesting, more strange, more chaotic, more livable, and more wonderful place.

Peter Suderman is features editor at Reason.

AI Is Nothing New

By Deirdre Nansen McCloskey

I will lose my union card as an historian if I do not say about AI, in the words of Ecclesiastes 1:9, “The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.” History doesn’t repeat itself, we say, but it rhymes. There is change, sure, but also continuity. And much similar wisdom.

So about the latest craze you need to stop being such an ahistorical dope. That’s what professional historians say, every time, about everything. And they’re damned right. It says here artificial intelligence is “a system able to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, and translation between languages.”

Wow, that’s some “system”! Talk about a new thing under the sun! The depressed old preacher in Ecclesiastes is the dope here. Craze justified, eh? Bring on the wise members of Congress to regulate it.

But hold on. I cheated in the definition. I left out the word “computer” before “system.” All right, if AI has to mean the abilities of a pile of computer chips, conventionally understood as “a computer,” then sure, AI is pretty cool, and pretty new. Imagine, instead of fumbling with printed phrase book, being able to talk to a Chinese person in English through a pile of computer chips and she hears it as Mandarin or Wu or whatever. Swell! Or imagine, instead of fumbling with identity cards and police, being able to recognize faces so that the Chinese Communist Party can watch and trace every Chinese person 24–7. Oh, wait.

Yet look at the definition of AI without “computer.” It’s pretty much what we mean by human creativity frozen in human practices and human machines, isn’t it? After all, a phrase book is an artificial intelligence “machine.” You input some finger fumbling and moderate competence in English and the book gives, at least for the brave soul who doesn’t mind sounding like a bit of a fool, “translation between languages.”

A bow and arrow is a little “computer” substituting for human intelligence in hurling small spears. Writing is a speech-reproduction machine, which irritated Socrates. Language itself is a system to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence. The joke among humanists is: “Do we speak the language or does the language speak us?”

So calm down. That’s the old news from history, and the merest common sense. And watch out for regulation.

Deirdre Nansen McCloskey holds the Isaiah Berlin Chair of Liberal Thought at the Cato Institute.

The post Is AI Like the Internet, or Something Stranger? appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Military-age males are a dangerous, scary lot. Best to have as few of them around, as possible. I should know. I used to be one myself.

In recent months, GOP politicians and other immigration restrictionists have been sounding the alarm about the presence of large numbers of “military-age males” among migrants crossing the southern border. There is no justification for such alarmism. “Military-age male” migrants don’t pose any special danger. Indeed, they are, on average, less dangerous than native-born citizens of the same description. Nor is there any reason to be much concerned about the fact that this group may be overrepresented among illegal migrants.

The definition of “military-age male” isn’t clear. But, most likely, it refers to men between the ages of about 18 and 45—the age group that includes most military personnel. If so, it’s not surprising that illegal migrants may be disproportionately drawn from this category. After all, most migrants are fleeing poor and repressive societies in hopes of finding greater freedom and opportunity. For obvious reasons, men in their prime working years are more likely to migrate in search of employment than children or the elderly.

In addition, illegal migration often involves risks created by participation in an illegal market. Undocumented migrants may be victimized by criminals, detained in awful conditions by US authorities, or suffer other dangers. On average, men are far more risk-acceptant than women. Thus, it isn’t surprising that they are more likely to be willing to risk the dangers of illegal migration. If you want to increase the proportion of women and children among migrants, the best way is to make legal migration easier, thereby making the process much less dangerous.

That said, the disproportion between men and women in the illegal migrant population is far from overwhelming. The Migration Policy Institute estimates that women make up 46% of the US undocumented immigrant population. That’s only modestly lower than their proportion of the overall US population (about 51%). And, far from seeing a surge in the percentage of single males among undocumented immigrants, 2023 actually saw an increase in the percentage of undocumented migrants who come in family groups.

One concern about military-age male migrants is the fear that they might be terrorists. But the number of people killed in terrorist attacks in the United States perpetrated by illegal migrants who crossed the southern border from 1975 to the present is zero. Either the incidence of terrorists among males who cross the southern border is extremely low, or they are extremely bad at committing actual acts of terrorism. Male undocumented migrants actually have a substantially lower incidence of terrorist attacks than native-born citizens do.

There is also no good evidence that military-age male migrants are somehow agents of foreign military forces, planning an invasion. Being a military-age male doesn’t mean you are likely to be a member of any actual military force or have any military skills. Similarly, the fact that younger males are, on average, better basketball players than women and older men, doesn’t mean that most young men are actually professional basketball players, or have more than rudimentary playing skill. Calling them “basketball-age males” doesn’t change that reality. I have criticized the “invasion” narrative in more detail here.

There is one kernel of truth to concerns about military-age males: men, especially young men, have a much higher crime rate than women do. They commit a hugely disproportionate percentage of violent and property crimes. For example, in 2019, according to FBI data, men accounted for almost 89% of those arrested for murder, and just under 97%of those arrested for rape.

However, if you worry about undocumented military-age males for this reason, you should worry about native-born ones even more. That’s because undocumented immigrants have much lower crime rates than native-born Americans do. In Texas between 2013 and 2022, for example, undocumented immigrants (2.2 homicides per 100,000 people per year), are about 36% less likely to commit homicide than native-born citizens (3.0 per 100,000 per year). And that’s without controlling for age and gender. If you do control for those variables, the gap between undocumented immigrants’ and natives’ crime rates becomes even larger, due to the greater proportion of younger males among the former.

Obviously, in any large group, there are going to be some dangerous individuals. The point is not that military-age male migrants are risk-free (they aren’t!), but that the incidence of that risk is low.

Conservatives rightly condemn left-wingers who claim all men are potential rapists. While the incidence of rape by men is vastly higher than that by women, the vast majority of men are not rapists and never will be. The same reasoning applies to right-wing scaremongering about “military-age male” migrants. Stigmatizing a large group based on the crimes of a small minority is wrong. And that’s especially true if the group’s overall crime rate is actually lower than that of comparably situated members of the rest of the population (in this case, male native-born Americans).

In sum, there is nothing surprising or sinister about the relative overrepresentation of “military-age males” among undocumented immigrants. And these men are actually, on average, less dangerous than native-born Americans of the same age and gender.

Obviously, there are many rationales for immigration restrictions and harsh border policies unrelated to fear of military-age males, or even to crime and terrorism, more generally. Some are more defensible than fear of military-age males. I have tried to address many of them in other writings, such as my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom. Here, I hope to help clear away a bad argument, so we can devote more attention to better ones.

The post Migration and the "Military-Age Male" Fallacy appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Deploying the precautionary principle is a laser-focused way to kill off any new technology. As it happens, a new bill in the Hawaii Legislature explicitly applies the precautionary principle in regulating artificial intelligence (AI) technologies:

In addressing the potential risks associated with artificial intelligence technologies, it is crucial that the State adhere to the precautionary principle, which requires the government to take preventive action in the face of uncertainty; shifts the burden of proof to those who want to undertake an innovation to show that it does not cause harm; and holds that regulation is required whenever an activity creates a substantial possible risk to health, safety, or the environment, even if the supporting evidence is speculative. In the context of artificial intelligence and products, it is essential to strike a balance between fostering innovation and safeguarding the well-being of the State’s residents by adopting and enforcing proactive and precautionary regulation to prevent potentially severe societal-scale risks and harms, require affirmative proof of safety by artificial intelligence developers, and prioritize public welfare over private gain.

The Hawaii bill would establish an office of artificial intelligence and regulation wielding the precautionary principle that would decide when and if any new tools employing AI could be offered to consumers.

Basically, the precautionary principle requires technologists to prove in advance of deployment that their new product or service will never ever cause anyone anywhere harm. It is very difficult to think of any technology ranging from fire and the wheel to solar power and quantum computing that could not be used to cause harm to someone. It’s tradeoffs all of the way down. Ultimately, the precautionary principle is the requirement for trials without errors that amounts to the demand: “Never do anything for the first time.”

With his own considerable foresight, the brilliant political scientist Aaron Wildavsky anticipated how the precautionary principle would actually end up doing more harm than good. “The direct implication of trial without error is obvious: If you can do nothing without knowing first how it will turn out, you cannot do anything at all,” he wrote in his brilliant 1988 book Searching for Safety. “An indirect implication of trial without error is that if trying new things is made more costly, there will be fewer departures from past practice; this very lack of change may itself be dangerous in forgoing chances to reduce existing hazards….Existing hazards will continue to cause harm if we fail to reduce them by taking advantage of the opportunity to benefit from repeated trials.”

Among myriad other opportunities, AI could greatly reduce current harms by speeding up the development of new medications and diagnostics, autonomous driving, and safer materials.

R Street Institute Technology and Innovation Fellow Adam Thierer notes the proliferation of over 500 state AI regulation bills like the one in Hawaii threatens to derail the AI revolution. He singles out California’s Safe and Secure Innovation for Frontier Artificial Intelligence Models Act as being egregiously bad.

“This legislation would create a new Frontier Model Division within the California Department of Technology and grant it sweeping powers to regulate advanced AI systems,” Thierer explains. Among other things, the bill specifies that if someone were to use an AI model for nefarious purposes, the developer of that model could be subject to criminal penalties. This is an absurd requirement.

As deep learning researcher Jeremy Howard observes. “An AI model is a general purpose piece of software that runs on a computer, much like a word processor, calculator, or web browser. The creator of a model can not ensure that a model is never used to do something harmful—any more so that the developer of a web browser, calculator, or word processor could. Placing liability on the creators of general purpose tools like these mean that, in practice, such tools can not be created at all, except by big businesses with well funded legal teams.”

Instead of authorizing a new agency to implement the stultifying precautionary principle in which new AI technologies are automatically presumed guilty until proven innocent, Thierer recommends “a governance regime focused on outcomes and performance [that] treats algorithmic innovations as innocent until proven guilty and relies on actual evidence of harm.” And just such a governance regime already exists, since most of the activities to which AI will be applied are currently addressed under product liability laws and other existing regulatory schemes. Proposed AI regulations are more likely to run amok than are new AI products and services.

The post AI Regulators Are More Likely To Run Amok Than Is AI appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

On April 13, Iran launched an unprecedented retaliatory drone and missile attack on Israel, leading the U.S. and its allies to reach once again for their favorite weapon of war—sanctions.

This knee-jerk reaction was as predictable as it was ill-founded, according to the scholarly research. In Nicholas Mulder’s 2022 treatise The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War, he traces the history of sanctions from the blockades in World War I to today’s morass of economic sanctions. Mulder concludes that “the historical record is relatively clear: most economic sanctions have not worked.”

Mulder’s treatise was followed by the book Backfire: How Sanctions Reshape the World Against U.S. Interests by Agathe Demarais. Drawing on her experience as an economic policy adviser for the diplomatic corps of the French Treasury, Demarais observes that sanctions tend to unite rather than isolate countries that are at odds with the U.S. and its allies, thereby transforming the geopolitical landscape and global economy to the detriment of U.S. influence.

The case of Iran is particularly illustrative of these points. In the recent How Sanctions Work: Iran and the Impact of Economic Warfare, authors Vali Nasr, Narges Bajoghli, Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, and Ali Vaez present a detailed study on the long-term impacts of economic sanctions on Iran. Nasr is an Iranian-born distinguished professor of international affairs and Middle East studies, a veteran diplomat, and a member of the U.S. State Department’s Foreign Affairs Policy Board. He and his collaborators studied the economic data and conducted long-form oral history interviews with 80 residents of Iran. The authors demonstrate that decades of Western sanctions, including the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign of 2018, have neither modified Iran’s international behavior in ways intended by policy makers nor precipitated any semblance of regime change.

Instead, sanctions have inflicted severe hardships on ordinary Iranians. The middle class has shrunk significantly from 45 percent in 2017 to 30 percent in 2020. If that wasn’t bad enough, Nasr and his colleagues estimate that the death toll attributable to the humanitarian catastrophes triggered by sanctions—such as food shortages and the breakdown of critical medical systems—has amounted to “hundreds of thousands.”

By imposing sanctions, the U.S. sought to crush Iran’s economy and make life so difficult for ordinary Iranians that they would rise up and either change the regime’s behavior or overthrow it altogether. However, this strategy relied on the assumption that Iranians would blame their misery on their own government and not those imposing the sanctions. Rather than blaming their government, Iranians have experienced a classic rally-’round-the-flag effect with sanctions inadvertently solidifying support for the regime. By creating animus against the U.S., sanctions have turned Iran’s hurting middle class into either de facto or de jure supporters of Iran’s leaders.

This is reflected in the interviews conducted by Nasr and his colleagues. Hamid, an interviewee and a disaster management specialist in Iran’s civil society sector, said of sanctions: “All they’ve done is make the Revolutionary Guard more powerful. Those of us in civil society are suffocating.”

Reza, a disillusioned university professor, echoed Hamid’s concerns: “If it’s not the nuclear issue, it’s our ballistic missiles. If it’s not our ballistic missiles, it’ll be human rights. If it’s not human rights, [the U.S.] will find another reason [to sanction Iran].”

Furthermore, Nasr and his co-authors contend that sanctions have driven the Iranian government to adopt more defensive and aggressive postures—the very behaviors that spurred the U.S. to impose sanctions on Iran in the first place. This pattern of behavior, where a sanctioned state becomes more militaristic and risk-taking, is well-documented and aligns with what economic theory predicts about actors with “nothing to lose.” This was highlighted by William L. Silber in The Power of Nothing to Lose: The Hail Mary Effect in Politics, War, and Business, in which he elucidates how extreme pressure during times of “war” can lead nations to take bold, often reckless actions.