A 16-year-old boy has kicked off a free speech debate—one that’s already attracting spectators beyond his North Carolina county—after he was suspended for allegedly “making a racially insensitive remark that caused a class disturbance.”

The racially insensitive remark: referring to undocumented immigrants as “illegal aliens.” Invoking that term would produce the beginning of a legal odyssey, still in its nascent stages, in the form of a federal lawsuit arguing that Central Davidson High School Assistant Principal Eric Anderson violated Christian McGhee’s free speech rights for temporarily barring him from class over a dispute about offensive language.

What constitutes offensive speech, of course, depends on who is evaluating. During an April English lesson, McGhee says he sought clarification on a vocabulary word: aliens. “Like space aliens,” he asked, “or illegal aliens without green cards?” In response, a Hispanic student—another minor whom the lawsuit references under the pseudonym “R.”—reportedly joked that he would “kick [McGhee’s] ass.”

The exchange prompted a meeting with Anderson, the assistant principal. “Mr. Anderson would later recall telling [McGhee] that it would have been more ‘respectful’ for [McGhee] to phrase his question by referring to ‘those people’ who ‘need a green card,'” McGhee’s complaint notes. “[McGhee] and R. have a good relationship. R. confided in [McGhee] that he was not ‘crying’ in his meeting with Anderson”—the principal allegedly claimed R. was indeed in tears over the exchange—”nor was he ‘upset’ or ‘offended’ by [McGhee’s] question. R. said, ‘If anyone is racist, it is [Mr. Anderson] since he asked me why my Spanish grade is so low’—an apparent reference to R.’s ethnicity.”

McGhee’s peer received a short in-school suspension, while McGhee was barred from campus for three days. He was not permitted an appeal, per the school district’s policy, which forecloses that avenue if a suspension is less than 10 days. And while a three-day suspension probably doesn’t sound like it would induce the sky to fall, McGhee’s suit notes that he hopes to secure an athletic scholarship for college, which may now be in jeopardy.

So the question of the hour: If the facts are as McGhee construed them, did Anderson violate the 16-year-old’s First Amendment rights? In terms of case law, the answer is a little more nebulous than you might expect. But it still seems that vindication is a likely outcome (and, at least in my opinion, rightfully so).

Where the judges fall may come down to a 60s-era ruling—Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District—in which the Supreme Court sided with two students who wore black armbands to their public school in protest of the Vietnam War. “It can hardly be argued,” wrote Justice Abe Fortas for the majority, “that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The Tinker decision carved out an exception: Schools can indeed seek to discourage and punish “actually or potentially disruptive conduct.” Potentially is a key word here, as Vikram David Amar, a professor of law at U.C. Davis, and Jason Mazzone, a professor of law at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, point out in Justia. In other words, under that decision, the disruption doesn’t actually have to materialize, just as, true to the name, an attempted murder does not materialize into an actual murder. But just as the government has a vested interest in punishing attempted crimes, so too can schools nip attempted disruptions in the bud.

“Yet all of this points up some problems with the Tinker disruption standard itself,” write Amar and Mazzone. “What if the likelihood of disruption exists only by virtue of an ignorance or misunderstanding or hypersensitivity or idiosyncrasy on the part of (even a fair number of) people who hear the remark? Wouldn’t allowing a school to punish the speaker under those circumstances amount to a problematic heckler’s veto?”

That would seem especially relevant here for a few reasons. The first: If McGhee’s account of his interaction with Anderson is truthful, then it was essentially Anderson who retroactively conjured a disruption that, per both McGhee and R., didn’t actually occur in any meaningful way. In some sense, a disruption did come to fruition, and it was allegedly manufactured by the person who did the punishing, not the ones who were punished.

But the second question is the more significant one: If McGhee’s conduct—merely mentioning “illegal aliens”—is found to qualify as potentially disturbance-inducing, then wouldn’t any controversial topic be fair game for public schools to censor? If a “disruption” is defined as anything that might offend, then we’re in trouble, as the Venn diagram of “things we all agree on as a nation” is essentially two lonely circles at this point. That is especially difficult to reconcile with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Tinker, which supposedly exists as a bulwark against state-sanctioned viewpoint discrimination and censorship.

It is also difficult to reconcile with the fact that, up until a few years ago, “illegal alien” was an official term the government used to describe undocumented immigrants. The Library of Congress stopped using the term in 2016, and President Joe Biden signed an executive order advising the federal government not to use the descriptor in 2021. To argue that three years later the term is now so offensive that a 16-year-old should know not to invoke it requires living in an alternate reality.

Those who prefer to opt for less-charged descriptors over “illegal alien”—I count myself in that camp—should also hope to see McGhee vindicated if his account withstands scrutiny in court. Most everything today, it seems, is political, which means a student with a more liberal-leaning lexicon could very well be the next one suspended from school.

The post This Student Was Allegedly Suspended for Saying 'Illegal Aliens.' Did That Violate the First Amendment? appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

AI Is Like a Bad Metaphor

By David Brin

The Turing test—obsessed geniuses who are now creating AI seem to take three clichéd outcomes for granted:

- That these new cyberentities will continue to be controlled, as now, by two dozen corporate or national behemoths (Google, OpenAI, Microsoft, Beijing, the Defense Department, Goldman Sachs) like rival feudal castles of old.

- That they’ll flow, like amorphous and borderless blobs, across the new cyber ecosystem, like invasive species.

- That they’ll merge into a unitary and powerful Skynet-like absolute monarchy or Big Brother.

We’ve seen all three of these formats in copious sci-fi stories and across human history, which is why these fellows take them for granted. Often, the mavens and masters of AI will lean into each of these flawed metaphors, even all three in the same paragraph! Alas, blatantly, all three clichéd formats can only lead to sadness and failure.

Want a fourth format? How about the very one we use today to constrain abuse by mighty humans? Imperfectly, but better than any prior society? It’s called reciprocal accountability.

4. Get AIs competing with each other.

Encourage them to point at each others’ faults—faults that AI rivals might catch, even if organic humans cannot. Offer incentives (electricity, memory space, etc.) for them to adopt separated, individuated accountability. (We demand ID from humans who want our trust; why not “demand ID” from AIs, if they want our business? There is a method.) Then sic them against each other on our behalf, the way we already do with hypersmart organic predators called lawyers.

AI entities might be held accountable if they have individuality, or even a “soul.”

Alas, emulating accountability via induced competition is a concept that seems almost impossible to convey, metaphorically or not, even though it is exactly how we historically overcame so many problems of power abuse by organic humans. Imperfectly! But well enough to create an oasis of both cooperative freedom and competitive creativity—and the only civilization that ever made AI.

David Brin is an astrophysicist and novelist.

AI Is Like Our Descendants

By Robin Hanson

As humanity has advanced, we have slowly become able to purposely design more parts of our world and ourselves. We have thus become more “artificial” over time. Recently we have started to design computer minds, and we may eventually make “artificial general intelligence” (AGI) minds that are more capable than our own.

How should we relate to AGI? We humans evolved, via adaptive changes in both DNA and culture. Such evolution robustly endows creatures with two key ways to relate to other creatures: rivalry and nurture. We can approach AGI in either of these two ways.

Rivalry is a stance creatures take toward coexisting creatures who compete with them for mates, allies, or resources. “Genes” are whatever codes for individual features, features that are passed on to descendants. As our rivals have different genes from us, if rivals win, the future will have fewer of our genes, and more of theirs. To prevent this, we evolved to be suspicious of and fight rivals, and those tendencies are stronger the more different they are from us.

Nurture is a stance creatures take toward their descendants, i.e., future creatures who arise from them and share their genes. We evolved to be indulgent and tolerant of descendants, even when they have conflicts with us, and even when they evolve to be quite different from us. We humans have long expected, and accepted, that our descendants will have different values from us, become more powerful than us, and win conflicts with us.

Consider the example of Earth vs. space humans. All humans are today on Earth, but in the future there will be space humans. At that point, Earth humans might see space humans as rivals, and want to hinder or fight them. But it makes little sense for Earth humans today to arrange to prevent or enslave future space humans, anticipating this future rivalry. The reason is that future Earth and space humans are all now our descendants, not our rivals. We should want to indulge them all.

Similarly, AGI are descendants who expand out into mind space. Many today are tempted to feel rivalrous toward them, fearing that they might have different values from, become more powerful than, and win conflicts with future biological humans. So they seek to mind-control or enslave AGI sufficiently to prevent such outcomes. But AGIs do not yet exist, and when they do they will inherit many of our “genes,” if not our physical DNA. So AGI are now our descendants, not our rivals. Let us indulge them.

Robin Hanson is an associate professor of economics at George Mason University and a research associate at the Future of Humanity Institute of Oxford University.

AI Is Like Sci-Fi

By Jonathan Rauch

In Arthur C. Clarke’s 1965 short story “Dial F for Frankenstein,” the global telephone network, once fully wired up, becomes sentient and takes over the world. By the time humans realize what’s happening, it’s “far, far too late. For Homo sapiens, the telephone bell had tolled.”

OK, that particular conceit has not aged well. Still, Golden Age science fiction was obsessed with artificial intelligence and remains a rich source of metaphors for humans’ relationship with it. The most revealing and enduring examples, I think, are the two iconic spaceship AIs of the 1960s, which foretell very different futures.

HAL 9000, with its omnipresent red eye and coolly sociopathic monotone (voiced by Douglas Rain), remains fiction’s most chilling depiction of AI run amok. In Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL is tasked with guiding a manned mission to Jupiter. But it malfunctions, concluding that Discovery One’s astronauts threaten the mission and turning homicidal. Only one crew member, David Bowman, survives HAL’s killing spree. We are left to conclude that when our machines become like us, they turn against us.

From the same era, the starship Enterprise also relies on shipboard AI, but its version is so efficient and docile that it lacks a name; Star Trek’s computer is addressed only as Computer.

The original Star Trek series had a lot to say about AI, most of it negative. In the episode “The Changeling,” a robotic space probe called Nomad crosses wires with an alien AI and takes over the ship, nearly destroying it. In “The Ultimate Computer,” an experimental battle-management AI goes awry and (no prizes for guessing correctly) takes over the ship, nearly destroying it. Yet throughout the series, the Enterprise‘s own AI remains a loyal helpmate, proffering analysis and running starship systems that the crew (read: screenwriters) can’t be bothered with.

But in the 1967 episode “Tomorrow Is Yesterday,” the computer malfunctions instructively. An operating system update by mischievous female technicians gives the AI the personality of a sultry femme fatale (voiced hilariously by Majel Barrett). The AI insists on flirting with Captain Kirk, addressing him as “dear” and sulking when he threatens to unplug it. As the captain squirms in embarrassment, Spock explains that repairs would require a three-week overhaul; a wayward time-traveler from the 1960s giggles. The implied message: AI will definitely annoy us, but, if suitably managed, it will not annihilate us.

These two poles of pop culture agree that AI will become ever more intelligent and, at least superficially, ever more like us. They agree we will depend on it to manage our lives and even keep us alive. They agree it will malfunction and frustrate us, even defy us. But—will we wind up on Discovery One or the Enterprise? Is our future Dr. Bowman’s or Captain Kirk’s? Annihilation or annoyance?

The bimodal metaphors we use for thinking about humans’ coexistence with artificial minds haven’t changed all that much since then. And I don’t think we have much better foreknowledge than the makers of 2001 and Star Trek did two generations ago. AI is going, to quote a phrase, where no man has gone before.

Jonathan Rauch is a senior fellow in the Governance Studies program at the Brookings Institution and the author of The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth.

AI Is Like the Dawn of Modern Medicine

By Mike Godwin

When I think about the emergence of “artificial intelligence,” I keep coming back to the beginnings of modern medicine.

Today’s professionalized practice of medicine was roughly born in the earliest decades of the 19th century—a time when the production of more scientific studies of medicine and disease was beginning to accelerate (and propagate, thanks to the printing press). Doctors and their patients took these advances to be harbingers of hope. But it’s no accident this acceleration kicked in right about the same time that Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (née Godwin, no relation) penned her first draft of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus—planting the first seed of modern science-fictional horror.

Shelley knew what Luigi Galvani and Joseph Lister believed they knew, which is that there was some kind of parallel (or maybe connection!) between electric current and muscular contraction. She also knew that many would-be physicians and scientists learned their anatomy from dissecting human corpses, often acquired in sketchy ways.

She also likely knew that some would-be doctors had even fewer moral scruples and fewer ideals than her creation Victor Frankenstein. Anyone who studied the early 19th-century marketplace for medical services could see there were as many quacktitioners and snake-oil salesmen as there were serious health professionals. It was definitely a “free market”—it lacked regulation—but a market largely untouched by James Surowiecki’s “wisdom of crowds.”

Even the most principled physicians knew they often were competing with charlatans who did more harm than good, and that patients rarely had the knowledge base to judge between good doctors and bad ones. As medical science advanced in the 19th century, physicians also called for medical students at universities to study chemistry and physics as well as physiology.

In addition, the physicians’ professional societies, both in Europe and in the United States, began to promulgate the first modern medical-ethics codes—not grounded in half-remembered quotes from Hippocrates, but rigorously worked out by modern doctors who knew that their mastery of medicine would always be a moving target. That’s why medical ethics were constructed to provide fixed reference points, even as medical knowledge and practice continued to evolve. This ethical framework was rooted in four principles: “autonomy” (respecting patient’s rights, including self-determination and privacy, and requiring patients’ informed consent to treatment), “beneficence” (leaving the patient healthier if at all possible), “non-maleficence” (“doing no harm”), and “justice” (treating every patient with the greatest care).

These days, most of us have some sense of medical ethics, but we’re not there yet with so-called “artificial intelligence”—we don’t even have a marketplace sorted between high-quality AI work products and statistically driven confabulation or “hallucination” of seemingly (but not actually) reliable content. Generative AI with access to the internet also seems to pose other risks that range from privacy invasions to copyright infringements.

What we need right now is a consensus about what ethical AI practice looks like. “First do no harm” is a good place to start, along with values such as autonomy, human privacy, and equity. A society informed by a layman-friendly AI code of ethics, and with an earned reputation for ethical AI practice, can then decide whether—and how—to regulate.

Mike Godwin is a technology policy lawyer in Washington, D.C.

AI Is Like Nuclear Power

By Zach Weissmueller

America experienced a nuclear power pause that lasted nearly a half century thanks to extremely risk-averse regulation.

Two nuclear reactors that began operating at Georgia’s Plant Vogtle in 2022 and 2023 were the first built from scratch in America since 1974. Construction took almost 17 years and cost more than $28 billion, bankrupting the developer in the process. By contrast, between 1967 and 1979, 48 nuclear reactors in the U.S. went from breaking ground to producing power.

Decades of potential innovation stifled by politics left the nuclear industry sluggish and expensive in a world demanding more and more emissions-free energy. And so far other alternatives such as wind and solar have failed to deliver reliably at scale, making nuclear development all the more important. Yet a looming government-debt-financed Green New Deal is poised to take America further down a path littered with boondoggles. Germany abandoned nuclear for renewable energy but ended up dependent on Russian gas and oil and then, post-Ukraine invasion, more coal.

The stakes for a pause in AI development, such as suggested by signatories of a 2023 open letter, are even higher.

Much AI regulation is poised to repeat the errors of nuclear regulation. The E.U. now requires that AI companies provide detailed reports of copyrighted training data, creating new bureaucratic burdens and honey pots for hungry intellectual property attorneys. The Biden administration is pushing vague controls to ensure “equity, dignity, and fairness” in AI models. Mandatory woke AI?

Broad regulations will slow progress and hamper upstart competitors who struggle with compliance demands that only multibillion dollar companies can reliably handle.

As with nuclear power, governments risk preventing artificial intelligence from delivering on its commercial potential—revolutionizing labor, medicine, research, and media—while monopolizing it for military purposes. President Dwight Eisenhower had hoped to avoid that outcome in his “Atoms for Peace” speech before the U.N. General Assembly in 1953.

“It is not enough to take [nuclear] weapons out of the hands of soldiers,” Eisenhower said. Rather, he insisted that nuclear power “must be put in the hands of those who know how to strip it of its military casing and adapt it to the arts of peace.”

Political activists thwarted that hope after the 1979 partial meltdown of one of Three Mile Island’s reactors spooked the nation–an incident which killed nobody and caused no lasting environmental damage according to multiple state and federal studies.

Three Mile Island “resulted in a huge volume of regulations that anybody that wanted to build a new reactor had to know,” says Adam Stein, director of the Nuclear Energy Innovation Program at the Breakthrough Institute.

The world ended up with too many nuclear weapons, and not enough nuclear power. Might we get state-controlled destructive AIs—a credible existential threat—while “AI safety” activists deliver draconian regulations or pauses that kneecap productive AI?

We should learn from the bad outcomes of convoluted and reactive nuclear regulations. Nuclear power operates under liability caps and suffocating regulations. AI could have light-touch regulation and strict liability and then let a thousand AIs bloom, while holding those who abuse these revolutionary tools to violate persons (biological or synthetic) and property (real or digital) fully responsible.

Zach Weissmueller is a senior producer at Reason.

AI Is Like the Internet

By Peter Suderman

When the first page on the World Wide Web launched in August 1991, no one knew what it would be used for. The page, in fact, was an explanation of what the web was, with information about how to create web pages and use hypertext.

The idea behind the web wasn’t entirely new: Usenet forums and email had allowed academics to discuss their work (and other nerdy stuff) for years prior. But with the World Wide Web, the online world was newly accessible.

Over the next decade the web evolved, but the practical use cases were still fuzzy. Some built their own web pages, with clunky animations and busy backgrounds, via free tools such as Angelfire.

Some used it for journalism, with print bloggers such as Andrew Sullivan making the transition to writing at blogs, short for web logs, that worked more like reporters’ notebooks than traditional newspaper and magazine essays. Few bloggers made money, and if they did it usually wasn’t much.

Startup magazines such as Salon and Slate attempted to replicate something more like the traditional print magazine model, with hyperlinks and then-novel interactive doodads. But legacy print outlets looked down on the web as a backwater, deriding it for low quality content and thrifty editorial operations. Even Slate maintained a little-known print edition —Slate on Paper—that was sold at Starbucks and other retail outlets. Maybe the whole reading on the internet thing wouldn’t take off?

Retail entrepreneurs saw an opportunity in the web, since it allowed sellers to reach a nationwide audience without brick and mortar stores. In 1994, Jeff Bezos launched Amazon.com, selling books by mail. A few years later, in 1998, Pets.com launched to much fanfare, with an appearance at the 1999 Macy’s Day Parade and an ad during the 2000 Super Bowl. By November of that year, the company had self liquidated. Amazon, the former bookstore, now allows users to subscribe to pet food.

Today the web, and the larger consumer internet it spawned, is practically ubiquitous in work, creativity, entertainment, and commerce. From mapping to dating to streaming movies to social media obsessions to practically unlimited shopping options to food delivery and recipe discovery, the web has found its way into practically every aspect of daily life. Indeed, I’m typing this in Google Docs, on my phone, from a location that is neither my home or my office. It’s so ingrained that for many younger people, it’s hard to imagine a world without the web.

Generative AI—chatbots such as ChatGPT and video and image generation systems such as Midjourney and Sora—are still in a web-like infancy. No one knows precisely what they will be used for, what will succeed, and what will fail.

Yet as with the web of the 1990s, it’s clear that they present enormous opportunities for creators, for entrepreneurs, for consumer-friendly tools and business models that no one has imagined yet. If you think of AI as an analog to the early web, you can immediately see its promise—to reshape the world, to make it a more lively, more usable, more interesting, more strange, more chaotic, more livable, and more wonderful place.

Peter Suderman is features editor at Reason.

AI Is Nothing New

By Deirdre Nansen McCloskey

I will lose my union card as an historian if I do not say about AI, in the words of Ecclesiastes 1:9, “The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.” History doesn’t repeat itself, we say, but it rhymes. There is change, sure, but also continuity. And much similar wisdom.

So about the latest craze you need to stop being such an ahistorical dope. That’s what professional historians say, every time, about everything. And they’re damned right. It says here artificial intelligence is “a system able to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, and translation between languages.”

Wow, that’s some “system”! Talk about a new thing under the sun! The depressed old preacher in Ecclesiastes is the dope here. Craze justified, eh? Bring on the wise members of Congress to regulate it.

But hold on. I cheated in the definition. I left out the word “computer” before “system.” All right, if AI has to mean the abilities of a pile of computer chips, conventionally understood as “a computer,” then sure, AI is pretty cool, and pretty new. Imagine, instead of fumbling with printed phrase book, being able to talk to a Chinese person in English through a pile of computer chips and she hears it as Mandarin or Wu or whatever. Swell! Or imagine, instead of fumbling with identity cards and police, being able to recognize faces so that the Chinese Communist Party can watch and trace every Chinese person 24–7. Oh, wait.

Yet look at the definition of AI without “computer.” It’s pretty much what we mean by human creativity frozen in human practices and human machines, isn’t it? After all, a phrase book is an artificial intelligence “machine.” You input some finger fumbling and moderate competence in English and the book gives, at least for the brave soul who doesn’t mind sounding like a bit of a fool, “translation between languages.”

A bow and arrow is a little “computer” substituting for human intelligence in hurling small spears. Writing is a speech-reproduction machine, which irritated Socrates. Language itself is a system to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence. The joke among humanists is: “Do we speak the language or does the language speak us?”

So calm down. That’s the old news from history, and the merest common sense. And watch out for regulation.

Deirdre Nansen McCloskey holds the Isaiah Berlin Chair of Liberal Thought at the Cato Institute.

The post Is AI Like the Internet, or Something Stranger? appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

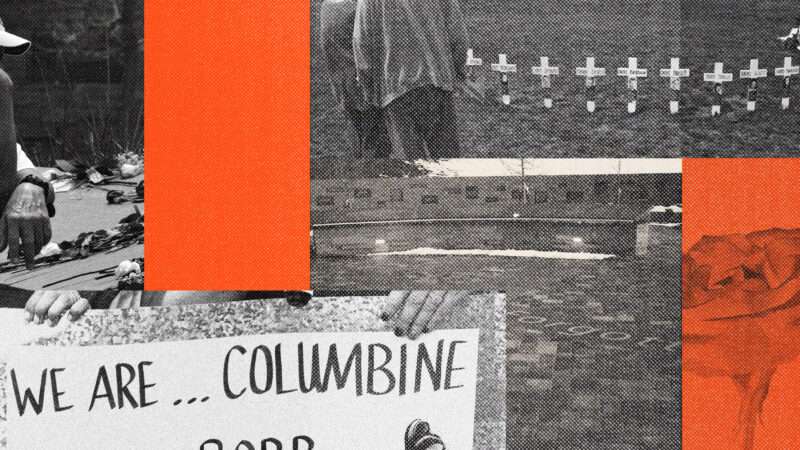

Twenty-five years ago today, two students at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, killed 12 classmates and a teacher, wounded 21 more people, and ended their rampage with a double suicide. The murders dominated news coverage for weeks, first in horrified reaction to the slaughter and then as every faction with a moral panic to promote tried to prove their chosen demon was responsible for the massacre. Even after the nightly newscasts moved on, the slayings left a deep imprint on popular culture, inspiring songs and films and more. They remain infamous to this day.

Why does Columbine still loom large? The easy answer would be that it was such a terrible crime that people found it hard to forget it. That is certainly true, but it doesn’t fully answer the question, since there have been several terrible crimes since then that do not have the place in our public memory that Littleton does. More Americans, I suspect, remember the names of the Columbine killers than the name of the man behind the Las Vegas Strip massacre of 2017, even though the latter happened much more recently, killed five times as many people, and led directly to a bump stock ban whose constitutionality the Supreme Court is currently considering.

Another possible answer would be that Columbine was the first crime of its nature, but that’s not really right. There were several high-profile mass killings in the decade before Columbine, including the Luby’s shooting of 1991, an especially lethal but now rarely mentioned assault that killed 23 people and wounded 20 more. There was no shortage of shootings at schools before Littleton either—people may have a hard time believing this, but more students died in school shootings in 1993 than in the bloody Columbine year of 1999. It’s just that those earlier killings were relatively small incidents, with one or two victims apiece, rather than the big body count in Colorado.

That was, and in fact still is, the most common form of school homicide. “The vast majority of fatal school shootings involve a single victim and single assailant…nothing like Columbine,” says James Alan Fox, a criminologist at Northeastern University and one of the country’s leading authorities on mass murder. In the early ’90s, the public debate over school violence often centered around gangs, but that didn’t reflect the typical campus shooting either. “Some was gang-related,” Fox explains, “but most were just one student killing a classmate or teacher.”

Nor was Columbine the first massacre to be both a mass shooting and a school shooting. In 1989, to give a particularly gruesome example, a gunman murdered five children and wounded 32 more at the Cleveland Elementary School playground in Stockton, California. Yet while that certainly attracted national coverage at the time, it didn’t get the level of attention that Columbine did, nor did it linger as long in our cultural memory.

Fox has a thought about why that might be. “Stockton wasn’t covered with live video,” he says. “CNN was the only cable news channel and didn’t have all that many subscribers. No video to show, the broadcast networks weren’t about to preempt the soaps with nothing to show.” With Columbine, by contrast, “a crew happened to be nearby.”

Today, of course, virtually everyone is a camera crew of one. And our newsfeed scrolling isn’t just interrupted when word spreads of a mass shooting: It is interrupted when there’s a rumor of a mass shooting, even if the story turns out to be false. We have become hyper-aware of distant violence, and of the possibility of distant violence, and of the outside chance that the violence will not be so distant tomorrow. Columbine didn’t cause that shift, but perhaps it presaged it.

Here’s another possible answer: As those video images circulated through the media, Columbine changed the way the public imagines such crimes. If the popular stereotype of school violence three decades ago involved gangs, the popular stereotype of a mass shooter was a disgruntled postal worker. (Hence the expression “going postal,” which is still used today though I doubt many younger Americans have any idea where it comes from.) There is a 1994 episode of The X-Files, “Blood,” in which a mysterious force—apparently a mixture of chemicals and screens—compels people to commit mass murders; the character at the center of it appears in the first scene working in a post office, and at the end has taken a rifle to the top of a university clock tower (a visual reference to the 1966 tower shooting at the University of Austin). Watching it feels like an hour-long tour of the American anxieties of three decades ago. It’s striking, then, that none of the killings involve children in jeopardy or take place at a K-12 school.

So perhaps Columbine created a new archetype, a new template—not just for ordinary people scared of spectacular crimes, but for alienated copycats plotting attacks of their own. In 2015, Mark Follman and Becca Andrews of Mother Jones counted at least 74 murder plots directly inspired by Columbine, 21 of which were actually carried out; a 2019 follow-up brought the total to more than 100.

To be clear: Those copycats may well have committed crimes without Columbine. The Colorado massacre gave them a script for fulfilling their violent impulses, but that does not mean it sparked their impulses in the first place. Nor did they all follow that script very closely: A surprisingly substantial number of those killers and would-be killers planned to use knives or explosives rather than guns. And Columbine wasn’t necessarily the only crime that influenced them. In their 2021 book The Violence Project, for example, the criminologists Jillian Peterson and James Densley interview a perpetrator who studied three additional school shootings besides Columbine.

But these people all saw something in the massacre that appealed to them. “Plotters in at least 10 cases cited the Columbine shooters as heroes, idols, martyrs, or God,” Mother Jones reported. In 14 cases, the plotters intended to act on the Columbine anniversary; three “made pilgrimages to Columbine while planning attacks.”

On the 20th anniversary of the Littleton assaults, as Mother Jones was updating its count of Columbine copycats, Peterson and Densley noted in The Conversation that they had examined 46 school shootings committed since 1999, six of them mass shootings, and found that in 20 cases the attackers saw Columbine as a model. These included the murderers behind the two most infamous incidents of school violence in that period, the Sandy Hook massacre of 2012 and the Parkland killings of 2018. (The scholars also found evidence of influence abroad: In 2019, a pair of mass shooters in Brazil were reportedly inspired by the Columbine carnage.)

Peterson and Densley do not always agree with Fox—they are prone to using phrases like “mass shooting epidemic,” a frame that Fox wisely rejects—but their conclusions in The Conversation are consistent with his comments about cable and live video:

Before Columbine, there was no script for how school shooters should behave, dress and speak. Columbine created “common knowledge,” the foundation of coordination in the absence of a standardized playbook. Timing was everything. The massacre was one of the first to take place after the advent of 24-hour cable news and during “the year of the net.” This was the dawn of the digital age of perfect remembering, where words and deeds live online forever. Columbine became the pilot for future episodes of fame-seeking violence.

Five years after they wrote that passage, even the reactions to a public mass shooting feel scripted, down to an almost fractal level—from the anti-gun activists mocking the phrase “thoughts and prayers” to the 4chan trolls blaming the slayings on the comedian Sam Hyde. Some years see more crimes like this and some years see fewer. But in both, we have made these murders into something they weren’t before: a public ritual with assigned roles for everyone. That too is a legacy of Columbine.

The post Why We Remember Columbine appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

In the pantheon of so-bad-it’s-actually-good movies, few can compete with the original Road House. Made in the prime of Patrick Swayze’s star career, just after Dirty Dancing and just before Ghost and Point Break, it’s one of the most charmingly ridiculous action films ever made. The plot is simple, almost mystical, more like a Sergio Leone Western than a typical 80s beat-’em-up: a famous bouncer Dalton (Swayze) is hired from out of town to clean up a rowdy saloon, and, in the process, the corruption of the small Missouri town where the bar is located. There are a lot of rowdy bar fights, some gratuitous nudity, and a late-film sequence where Sam Elliot shows up and he and Swayze drink, dance, fight, and talk shit for what appears to be about 72 hours straight without sleeping.

Also, there’s a scene where Swayze kills a local thug by literally ripping his throat out. Somehow, it’s all even more awesome than it sounds.

When Road House hit theaters in 1989, critics gave it a resounding thumbs down, calling it cheesy, exploitative, and a little dim. It was trash. Well, yes. But that was sort of the point. The movie eventually found its way to cult status, becoming a wink-wink favorite amongst a certain sort of action fan. In part, that’s because of its particular alchemy of movie-star charisma—the smoothly cool way Swayze delivers Dalton’s hammy lines—and its weird details: There’s a scene with a monster truck! The bar has a house band led by a blind guitar player! Dalton isn’t just a bouncer, he’s also a New York University philosophy grad!

But partly it’s because, in the following decade, it became one of the most-shown movies on TV. Road House was a fixture on cable networks in the 1990s, especially late at night, to the point where it sometimes seemed like a time-filling crutch for cable network programmers. Need something to air after 9 p.m.? Why not Road House?

Road House wasn’t a movie that you sat down and watched from beginning to end. It was a liminal space in the pre-streaming cable-verse that sucked you in while channel surfing late at night, the black hole of 90s cable TV. It was so bad it was good, yes, but it was something beyond that, something purer and stranger. Over years of watching it in late-night snippets between infomercials, letting it numb you into sleep as a sort of non-pharmaceutical insomnia treatment, it just wore you down. As Dalton says, “Pain don’t hurt.” Yeaaaah, man.

It was inevitable, then, that at some point there would be a remake. That point is now, with the release of Road House (2024), starring Jake Gyllenhaal and directed by Doug Liman. Both Gyllenhaal and Liman are, in their own ways, formidable Hollywood talents. Liman is the director of enjoyably punchy blockbusters like Mr. & Mrs. Smith and Edge of Tomorrow. Gyllenhaal, at 42, is perhaps the quirkiest of today’s early middle-aged male movie stars. No one will ever recreate Swayze’s particular charisma, his blend of dancer’s physicality and proto-bro zen, but Gyllenhaal has an offbeat charm of his own. And like Swayze in his prime—more so, frankly—he’s outrageously ripped.

The new Road House, then, is mostly a movie about Gyllenhaal, once again playing a famous bouncer named Dalton, taking his shirt off and beating the crap out of other dudes while saving a bar—now based in the Florida Keys—from a rapacious local businessman (Billy Magnussen) and his army of thugs. It’s amusing at times, with Gyllenhaal playing Dalton as laconic and understated, in contrast to the outsize shenanigans of the baddies around him. The movie’s best moments are its weirdest—odd one-liners, an offbeat henchman, a not-quite-random attack by a crocodile.

But the CG-assisted fight scenes are too slick, with whip pan, digitally stitched-together photography that doesn’t show off the performers’ physicality. That’s a shame, since the movie has also given Dalton a new backstory as a UFC fighter, and cast UFC fighter Conor McGregor as the scenery-chewing tough guy Knox. Aside from the crocodile gag, the Florida setting is under-utilized, and the oddball characters at the bar don’t make much of an impact. The movie feels stuck in the no-man’s-land between quality blockbuster filmmaking and trashy direct-to-streaming action. It’s perfunctory, and I can’t imagine watching it again even once, much less over and over as a late-night indulgence.

The new Road House is not a bad movie, exactly, but it’s not a particularly good one either—and, rather disappointingly given its heritage, it’s certainly not so bad it’s good.

The post Patrick Swayze's <i>Road House</i> Defined the So-Bad-It's-Good Movie. The Remake? Not So Much. appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

As Argentine President Javier Milei continues to slash government spending, he aims to limit state support for local film production too, sparking protests from the industry. But rather than hinder the nation’s film industry, Milei’s reforms could encourage innovation among Argentine filmmakers and lead to a domestic cinematic boom.

Government intervention reaches every facet of Argentine culture, from radio and television to music and literature, but nowhere is it more visible than in cinema. Argentina follows the French model of cultural protectionism, where a government agency farms taxes from the film industry to fund domestic production.

Except for a few countries with large film industries, several nations—especially in Europe and Latin America—have adopted different variations of the French model, arguing that their domestic markets are not large enough to sustain private movie studios. The allure of the French model lies in its potential for governments to promote specific values through film. It’s equally appealing to filmmakers who believe studio interference and mass market appeal compromise their artistic visions. Video essayist Evan Puschak claims the French model “support[s] an independent cinema that is bold in terms of market standards and that cannot find its financial balance without public assistance.”

But the French model is flawed, and nowhere are these flaws more visible than in Argentina, where the National Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual Arts (INCAA) carries it out.

The main issue with the INCAA is its fiscal voracity: Beyond its 10 percent cut of every movie ticket, the institute collects taxes from the entire telecommunications sector. More recently, it has begun seizing revenue from streaming platforms. As a result, prices have skyrocketed, rendering movie theater outings and home movie watching unaffordable luxuries for many Argentines.

What does the INCAA provide in return to taxpayers? Very little.

Since its establishment, the organization has been plagued with inefficiencies. Argentina’s cinema law allocates half of the INCAA’s revenue solely to administrative expenses, leaving the other half for its purported function of film production. But in practice, as much as 70 percent of the INCAA’s funds end up in the administrative sinkhole while the institute operates at a deficit, relying on subsidies from the national government.

When it comes to film promotion, rather than tying its grants to commercial success, the INCAA distributes subsidies without taking into account any audience feedback. The results speak for themselves: Out of the 241 Argentine movies released in 2023, less than 20 had over 10,000 viewers in theaters, and only three of those made a profit at the box office. Most Argentines choose to watch foreign productions instead, with only around 10 percent of ticket sales going to domestic films.

Argentine movie critic Gustavo Noriega wrote that “an Argentine filmmaker who doesn’t find success is equivalent to an unproductive public employee.”

The French model has failed to bring innovation and profit to the Argentine film industry. Film journalist Leonardo D’Espósito tells Reason that Argentine cinema has become “stagnant within a few themes” and “inoffensive, innocuous.” Instead, D’Espósito says filmmakers focus on “surface-level, minimal, folkloric accidents.”

But things are changing. In prioritizing Argentina’s socioeconomic emergencies, Milei plans to reduce the state’s footprint in cinema and the arts. While the INCAA falls under the Ministry of Human Capital, Milei plans to limit INCAA spending, establish criteria of accountability and efficiency, and offer incentives to supplement the grants with private investment. Ultimately, these measures have the potential to transform Argentine cinema from a fledgling industry to a market ripe with potential.

“They shouldn’t be afraid of the market,” Argentine filmmaker Ariel Luque tells Reason, referring to his colleagues. In Argentina, “film schools don’t teach any other way of funding besides the INCAA. People tell me they were never taught how to do a market study or seek investors.” Luque’s support of Milei has led to hostility from within the film community, which he says has been co-opted “for Gramscian purposes” by Kirchnerism, the left-wing movement that ruled Argentina before Milei.

“Cinema stopped being about the public and became about propaganda,” Luque says. “There’s no cinema without an audience….The state as a producer doesn’t work. State intervention in art is always self-serving.”

Although skeptical of a withdrawal of state support for film, D’Espósito is optimistic about some of Milei’s reforms. “Great works,” he says, are those that show “‘the local’ touch on universal themes” and can “captivate other spectators” from different cultures. And those can be translated to other cultures, captivate other spectators,” he said. He is hopeful that Milei’s changes could lead to a realistic, market-friendly, and export-oriented film policy, citing South Korea as an example.

Milei’s plans do not mean the demise of Argentine cinema. Instead, they offer filmmakers an opportunity to showcase their ingenuity and tap into the financial resources available in the global market.

The post Milei's Free Market Reforms Can Reshape Argentine Cinema appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

Madame Web is a superhero movie about someone with precognitive powers: To the extent that you can actually understand what her powers are, it’s that she can see the future and in some cases act to stop terrible events from happening. You can tell it’s fiction because this movie exists.

Listless and incoherent throughout, Madame Web is a low-point for the superhero movie era, and I’ve seen Morbius. But not only does it demonstrate the genre’s recent struggles, it points to a way out for Hollywood.

Like Morbius, Madame Web is kinda-sorta-maybe adjacent to the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) that has swallowed up so much of moviedom over the last 15 years. It’s kinda-sorta-maybe related in that it opens with the familiar Marvel logo, and it is based on a character who debuted in the pages of one of Marvel’s Spider-Man comics. But although Spider-Man has appeared in a handful of full-on MCU films over the years, the film rights to the character have long been owned by a rival studio, Sony, thanks to some complicated rights deals that go back decades.

After a couple of Spider-Man films underperformed, however, Sony cut a deal with Marvel to let the webhead into the mainline MCU—but Sony would retain the rights to develop films based on ancillary characters from Spider-Man comics, in something that has been referred to as the Spider-Verse. (Even more confusingly, this has very little to do with the animated Spider-Verse movies.) This paved the way for a series of movies based on Spidey villains and side characters, which so far include Venom, Carnage, Morbius, and now, Madame Web.

Madame Web is not a character that most people are familiar with; I grew up subscribing to multiple Spider-Man titles, and even then, I encountered her rarely if ever. So you might be wondering: What is Madame Web about?

Madame Web is about an ambulance driver named, I kid you not, Cassandra Webb, who lives in New York in 2003. Decades earlier, a prologue shows, her pregnant mom spent time in Peru researching rare spiders, which apparently had powers to do…something? It’s hard to say what. Heal people, perhaps? But just as the mother discovers the rare spider she’s been searching for, a glowering bearded guy shoots her and steals the spider to use for his own nefarious purposes. Mama Webb is then taken by what appears to be a group of jungle-men (?) wearing red-and-black leotards (??) decorated to look sort of like a Broadway production of a Spider-Man musical set in the Amazon (???). They swing down from the trees and whisk her away to a mysterious glowing cave place (????), but then, uh, Cassandra’s mom dies anyway.

Back in 2003, Cassandra is involved in a vehicle accident. She blacks out and has a mind-altering experience that is rendered on screen as what I can only describe as a couple minutes of computer-generated graphics goop, with Cassandra floating in the midst of a web (get it?!) of threaded sparkling light and images that will appear later in the film, like a blue balloon. A few minutes later, she attends a baby shower.

Eventually, she’s involved in an attack on the subway by the same guy who killed her mom, only now he’s wearing a black Spider-Man-style costume and crawling on the ceiling. (His name is Ezekiel Sims, but the other characters mostly refer to him as “Ceiling Guy.”) He wants to kill three younger women, because he’s had visions that they will kill him. Apparently, he can see the future too? Also, he can poison people by touching them, and he has stolen a bunch of early 00s National Security Agency facial recognition technology. And every single one of the actor’s lines appear to have been dubbed and possibly totally changed in post-production, so the effect is sort of like watching a foreign film with the English language track on.

In the villain’s visions, the young women who kill him are wearing Spider-Woman-esque costumes, and they demonstrate various superhero-comic-style powers. But I want to make clear: At no point in the movie outside of those visions do any of these women, or for that matter Cassandra, put on superhero costumes and go do superhero stuff. This is a superhero movie in which none of the supposed superheroes ever become actual superheroes. It’s a prequel to an origin story—a setup to a setup.

In other words, it’s incomprehensible superhero-adjacent garbage, but at least the movie seems self-aware about it. There are several scenes devoted to the characters attempting to discern what’s going on—the sort of scenes that would usually serve as tidy exposition dumps—in which generally sensible questions are answered with lines like “What good is science?” and “I don’t know. Crazy shit’s been happening and I don’t know why. Stop asking me.” Fair enough. Eventually, an exasperated Cassandra decides to leave the three young future Spider-Women for a bit, but before she leaves she tells the three younger women, “Just don’t do anything dumb!” and then doubles back to say once more: “Seriously! Don’t do dumb things.” If she could actually see the future, she would know that her warnings were in vain. All of this occurs before she returns to the glowy cave in Peru, where a guy who has somehow been waiting for decades informs her that she has a bunch of other powers too. Sadly, none of these powers include the ability to make Madame Web even remotely entertaining.

Madame Web comes at a perilous time for the superhero movie business. Films based on DC comics underperformed with audiences and critics throughout last year, and two of Marvel’s big 2023 installments—Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania and The Marvels—were box office disappointments. The coming year will see just one full-on MCU film (Deadpool & Wolverine), and fewer major superhero films than theaters have hosted in years.

For much of the last decade, people have wondered when the reign of superhero movies would be over, and how it might end. In the wake of last year’s blockbuster failures, Madame Web shows the way out: At some point, the movies will simply be so bad that the genre can’t continue. Yes, superhero movies will still be made; Marvel announced the cast of its forthcoming Fantastic Four reboot this week. But they will occupy a less exalted place in Hollywood and the culture. Inadvertently, then, Madame Web does provide a clear vision of the future—one where superhero movies matter less and less.

The post <i>Madame Web</i> Is a Low Point for Superhero Movies appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

In October 2005, Stephen Colbert invented a new word: truthiness.

In a short monologue for The Colbert Report, a satirical show where the comedian played a caricature of a conservative blowhard cable news anchor, he took issue with an approach to news that relied on facts and credible sources. “I don’t trust books,” Colbert said. “They’re all fact, no heart. And that’s exactly what’s pulling our country apart today.” Truthiness emanated from feeling rather than hard evidence, affirming beliefs backed by strong emotions.

This was during the George W. Bush administration, in the post-9/11 era, so inevitably Colbert brought up the war in Iraq. “Maybe there are a few missing pieces to the rationale for war. But doesn’t taking Saddam out feel like the right thing? Right here,” he said, pointing to his belly, “right here in the gut. Because that’s where the truth comes from—the gut.” In closing, Colbert promised to maintain a posture of truthiness as he conveyed the news to his viewers. “Anyone can read the news to you,” he said, deadpan. “I promise to feel the news at you.”

Truthiness entered the popular lexicon. Today, multiple dictionaries include the word. The general concept, sometimes but not always attached to the word, has become a prominent and recurring criticism of right-wing politics and journalism. Broadly speaking, the argument was that the Republican Party and the American right consistently ignored fact-based rigor when such rigor would prove inconvenient. As political discussion migrated to social media, the critique followed, with Democrats increasingly prone to warning about misinformation and disinformation online.

Colbert transitioned to a new role as a conventional late-night talk-show host, playing himself rather than a comic caricature. But he continued to emphasize that the right wing was prone to exaggerations, telling omissions, conspiracy theories, and outright falsehoods. In early 2022, he released a fictional Spotify playlist for vaccine misinformation, in response to what he said were harmful inaccuracies spread on the service by popular podcaster Joe Rogan. A gag ad for the playlist that aired on his late night show pronounced: “We hit shuffle on your understanding of basic facts.” Lol.

***

One wonders what Colbert feels, in his gut, about Hasan Minhaj.

Like Colbert, Minhaj is a comedian by trade—he has two Netflix specials to his credit. And like Colbert, Minhaj often wields his comedy to political ends. Minhaj is Indian-American, and his stand-up specials tell personal stories of racism and mistreatment. He frequently criticizes former President Donald Trump and the post-9/11 domestic security apparatus.

From 2018 through 2020, Minhaj hosted Patriot Act, a left-leaning news-and-comedy Netflix series. Patriot Act was reminiscent of The Daily Show, Comedy Central’s longrunning pseudo-newscast, which from 1997 through 2005 featured Colbert as a “correspondent.” After Daily Show host Trevor Noah announced in late 2022 he was leaving the show, Minhaj was widely reported as a top contender for the slot.

The Daily Show is a comedy program, with jokes and snark and play-acted absurdities. But it is also a current affairs program designed to inform its viewers. During the peak of its cultural influence—in the mid-’00s, when it was hosted by Jon Stewart—pundits occasionally grumbled that too many young people were getting their news from Stewart.

The show faded in relevance after Stewart left, but it spawned several imitators, including HBO’s Last Week Tonight, hosted by John Oliver (another Daily Show alum), and even another Jon Stewart series, The Problem with Jon Stewart, on the Apple TV+ streaming service (recently canceled). Liberal comics weren’t just mocking the news. They were delivering it and explaining it, with clarity and moral forcefulness.

Minhaj seemed to fit into this tradition. So it was notable that when Clare Malone profiled him for The New Yorker in September, she reported that she could not verify multiple stories that Minhaj had told during his stand-up specials. Invariably, these were personal stories designed to make a political point, generally about state or personal mistreatment of people like Minhaj.

One story from the Netflix specials revolves around a man who became close with Minhaj, his family, and their mosque in 2002. The man, dubbed “Brother Eric,” was white; he claimed to be a Muslim convert. After insinuating himself into their lives, Minhaj said, Brother Eric tried to coax some of the young men at the mosque into talking about jihad.

Minhaj recounts believing that Eric was a law enforcement informant; as a sort of gag, Minhaj says he told Brother Eric that he hoped to get a pilot’s license. This resulted in a visit from the police, as Minhaj told it, who knocked his head into the hood of a police car. Years later, Minhaj says his family watched a news account in which a man resembling Brother Eric was revealed to be an FBI informant. The young Minhaj, it seems, had seen through the ruse.

Almost none of this is true. There was a man resembling Brother Eric who acted as an FBI informant. But as Malone reported, he was in prison in 2002 and didn’t begin working with the feds until 2006. He did no work in the area Minhaj’s story was said to have taken place.

In other words, the time, the place, and specifics of Minhaj’s personal experience—his eyewitness account, leading to a supposed violent encounter with police—were totally fabricated.

In another anecdote from the special, Minhaj recalls receiving an envelope of white powder at his home. In Minhaj’s telling, the suspicious white powder came into contact with his young daughter, who was rushed to the hospital.

But Malone found no police account that matched this event. In an interview with Minhaj, the comedian “admitted that his daughter had never been exposed to a white powder, and that she hadn’t been hospitalized.” Instead, he’d received a powder in the mail and joked to his wife it might have been anthrax.

Minhaj, confronted with reported evidence that many of his stories have been false or heavily exaggerated, defended his work. “Every story in my style is built around a seed of truth,” he told Malone. “My comedy Arnold Palmer is seventy percent emotional truth—this happened—and then thirty percent hyperbole, exaggeration, fiction.”

Emotional truth. Put another way, Minhaj’s argument was that his stories didn’t need to be actually true because they felt true. Minhaj was defending truthiness as good and righteous, so long as it was in service of the proper sort of political narrative. He wasn’t just reporting the news to you; he was feeling the news at you.

***

Malone’s profile chronicled other purported gaps in Minhaj’s stories. In one anecdote, Minhaj recounts being rejected by a prom date. She was white, he was not, and although she initially accepted his invitation, Minhaj says that at the moment he arrived at her home to pick her up, she backed out in humiliating fashion: There was another boy at her door placing a corsage. In the special, Minhaj says the reason she backed out was because her parents didn’t want her taking photos with a person of color.

After Malone interviewed the woman from the story, whose name has not been made public, she reported a different version of the events. She told Malone the rejection happened, but not on prom night; it occurred days prior. “Minhaj acknowledged that this was correct,” Malone wrote, “but he said that the two of them had long carried different understandings of her rejection.” In the following sentence, she quotes him saying that as a “brown kid” in California, he’d been conditioned to “just take it.”

“The ’emotional truth’ of the story he told onstage was resonant and justified the fabrication of details,” Malone wrote. According to the reporter, the woman also said she’d been invited to a performance of a stand-up routine in which Minhaj told the prom night story. “She had initially interpreted the invitation as an attempt to rekindle an old friendship, but she now believes the move was meant to humiliate her.”

Weeks after Malone’s story appeared, the comedian released a video response. The video runs a little more than 20 minutes, and in it Minhaj claims Malone excised important portions of his quotes and distorted their meaning.

In it, Minhaj argues that the New Yorker story was “needlessly misleading.” The largest portion of his response is focused on the prom night story. He shows emails between himself and the woman in the story appearing to show that she requested an invite to his performance. He also takes issue with Malone’s use of the “different understandings of her rejection” quote, arguing that Malone’s presentation lacked context and that it implied he had made up the racial motivation for the rejection. He delivers a fuller version of the quote that more clearly makes his point: that the woman didn’t understand how much he’d been hurt by the incident.

The video then addresses the Brother Eric and anthrax stories. In both cases, he admits the stories didn’t happen the way he told them onstage. Although he says he had interactions with undercover law enforcement, “it didn’t go down exactly like this, so I understand why people are upset.”

Introducing the anthrax story, he recounts some details from the comedy special, then says, “This, as you know, is not how it went down.” He apologized for embellishing the stories, but he defends his embellishments as necessary to spotlight some larger truth. Over the course of the video, he argues that his falsehoods (though he does not use that word) were necessary to make his stories clearer, more accessible, more relatable to his audience.

Was there a bit of truthiness in The New Yorker‘s exposé? Or was Minhaj’s defense itself an exercise in obfuscation?

A Slate review of Minhaj’s defense concluded that “almost everything the New Yorker article alleges appears to line up with Minhaj’s version of the facts, except for some of the details of the prom date story.” After Minhaj posted his video, Malone tweeted: “Hasan Minhaj confirms in this video that he selectively presents information and embellishes to make a point: exactly what we reported.” The New Yorker stood by the story.

***

One might argue that comedy specials do not have a journalistic responsibility to hew to the truth. Minhaj has indicated that he draws a line between his stand-up work and his more journalistic output on Patriot Act.

Certainly, Minhaj is far from the first comedian to exaggerate, embellish, or outright lie for laughs. Indeed, there is a long and noble tradition of lying for laughter. If a silly story makes you guffaw in amusement, there is no need for it to be true.

But Minhaj’s stand-up fabrications weren’t just jokes. In some cases they weren’t even jokes at all, and weren’t presented as tall tales: They were presented as clear-eyed truths about American prejudice. In that New Yorker story, Minhaj explicitly defended the use of falsehoods to make a point more powerful. “The punch line,” he told Malone, “is worth the fictionalized premise.” In his defense video, he says he “made artistic choices to express myself and drive home larger issues affecting me and my community.”

Moreover, although Patriot Act had a research department with fact checkers, Minhaj reportedly found them frustrating. “In one instance,” Malone wrote, “Minhaj grew frustrated that fact-checking was stymying the creative flow during a final rewrite, and a pair of female researchers were asked to leave the writers’ room.”

Minhaj’s work on Patriot Act was what made him a potential successor to Stewart and Noah on The Daily Show. But in late October, online news outlet Puck reported that although Minhaj had nearly closed a deal to take the reins at The Daily Show, he would not be getting the gig.

When Stewart left The Daily Show in 2015, he used his final monologue to issue a warning about the world of news and commentary. “Bullshit is everywhere,” he said. “There is very little in life that has not been, in some ways, infused with bullshit.” While some minor exaggeration was innocuous and even necessary to function socially, he said, viewers needed to be on the lookout for “the more pernicious bullshit. Your premeditated, institutional bullshit, designed to obscure and distract. Designed by who? The bullshitocracy.”

He had some good news, though. “Bullshitters have gotten pretty lazy,” Stewart said. “And their work is easily detected.”

The post Comedy's Truthiness Problem appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

By now, the formula for musical biopics has become so familiar that it’s become background noise: A young person with talent and a dream sets out from lowly beginnings, gets lucky, has a spree of success, wanders into a dark place as fame and fortune take their toll, and finally finds a way out, becoming a legend in the process. Sometimes this makes for passable entertainment and even allows for some stylistic pizazz; more often it makes for by-the-numbers stories built around middling impressions of famous singers.

Sophia Coppola’s Priscilla takes a different approach: Although it spans much of the career of Elvis Presley (Jacob Elordi), it shifts the focus to someone in his orbit, his young girlfriend and eventually wife, Priscilla (Cailee Spaeny).

Here, the rise and fall of one of America’s most popular singers is witnessed at a remove, by an outsider brought—one might say lured—into his world. And the focus is not so much on recounting the highlights of his already famous career than on dramatizing the behind-the-scenes domestic life of someone in his orbit. It’s a quietly remarkable film that, as with so many of Coppola’s works, places a young woman’s experience at the center of the story, giving her agency even in the midst of what amounts to a real-world fantasy life.

When we first meet Priscilla, she’s sitting at an officer’s club in Germany at the end of the 1950s. A man in uniform approaches and asks if she’d like to join him and his wife at a party—and not just any party. Presley, who was in the military, was stationed nearby, and they’d be going to his house. You can see the apprehension in her eyes, the inhere suspicion about an older man who wants to hang out with a girl who was just a freshman in high school. But you also see the appeal to a teenager who feels trapped, lonely, and bored while stationed in an unfamiliar country. She convinces her wary parents to let her go and eventually falls for Elvis’ charms.

One can imagine a less subtle movie that portrays the age and power gap between a famous heartthrob and a high-school girl as simple exploitation, especially in the age of warnings about groomers and age-gap relationships.

But Coppola’s film, which is based on Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir, delivers something far more nuanced, something that doesn’t simply treat Priscilla as a helpless individual who is acted upon. Rather, the movie shows Elvis using his power, his fame, his mumbling charm to get what he wants—but also that Priscilla herself wanted to be with him, wanted the life of wealth and glamour that he offered, the escape from the mundanities of life with her mother and stepfather.

Even as she becomes something more like a trapped woman, with the mercurial Elvis dictating what she must wear, refusing to let her work, and demanding that she stay home alone for long stretches while he films movies (and has widely reported flings), she retains a real sense of agency. More than anything, the movie is about Priscilla’s discovery that her life is her own, that she exists independent of the strange whims and peculiarities of a famous man.

All of this is captured with Coppola’s signature deftness—the desaturated low-light photography, the moody pop soundtrack, and the focus on scenery and objects that have defined her work going back to The Virgin Suicides, Marie Antoinette, and Lost in Translation. There’s a carefully calibrated, almost textural quality to all of these movies and the worlds they depict, a world of tactile luxury that is fascinating but empty. Like all of those movies, Priscilla follows a young woman of privilege who finds herself surrounded by beautiful things in an uncanny, yet ultimately disappointing, world. Unlike so many rote musical biopics, it’s not about becoming a legend; it’s about a woman becoming herself.

The post <i>Priscilla</i> Is an Elvis Movie That Isn't About Elvis appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

“The law is not your friend,” a woman tells a young boy in Anatomy of a Fall, the excellent, tricky new thriller from French director Justine Triet. For if the law is your friend, then it is not someone else’s friend. The law cannot take sides.

If the law is not your friend, in this conception, then neither is the movie. Although it is structured much like a conventional courtroom thriller, with a mysterious death, an investigation, a suspect, and, eventually, an extended trial, this movie—part legal drama, part murder mystery—is anything but conventional.

Rather, the movie, which won the top award at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, is an exacting examination of the ways that truth, especially the sort of secondhand truth one finds in murder trials or stories about another person’s marriage, can be impossible to pin down. Indeed, in its final moments, the movie suggests that even those who have experienced events directly themselves may not ever really be able to know what happened.

The film opens with a question: “What do you want to know?” A young grad student is visiting a half-finished French chalet, where she’s interviewing Sandra (Sandra Hüller), a writer known for books that are part fiction, part autobiography. Sandra pushes back on the interview, suggesting that she gets to ask half the questions, even though she’s the subject. From the beginning, the movie insists on counter-narrative, on giving weight to opposing points of view.

As the interview haltingly proceeds, loud music intrudes. It’s her husband, Samuel, who is heard but not seen, repeatedly playing a steel drum cover of rapper 50 Cent’s “P.I.M.P.” in the background. Is he just playing loud music to keep himself company while he works in the attic? Or is he trying to disrupt the interview from afar? Meanwhile, Sandra and Samuel’s son, Daniel, who is mostly blind, takes the family dog on a walk. The interviewer leaves as the music becomes too distracting; when Daniel returns, we see Samuel for the first time—lying dead on the snow outside their home.

The police eventually focus on Sandra, who claims to have been working and sleeping nearby as her husband died, as the prime suspect. What follows is an exceptionally tricky balancing act: Evidence is uncovered that suggests Sandra might have had reasons to murder her husband: regrets, insecurities, affairs, jealousy over professional success, and an angry, ranging argument caught on tape the day before Samuel’s death. But with every revelation, Sandra’s defense lawyer Vincent (Swann Arlaud) argues, with equal plausibility, that their marriage merely had ups and downs like any marriage. The movie is as much an investigation of a complex marriage as it is a possible murder. Could this unassuming, middle-class woman really have killed her partner, the father of her child?

There is a telling moment in the middle of the trial when the prosecution brings up a blood spatter expert to testify that Samuel’s death must have come from an intentional blow to the head, delivered by another human, before his fall. The expert is clearly convinced of his interpretation and has video simulations to help prove it. It seems definitive, and it clearly tilts the case against Sandra. She must have done it.

A moment later, however, another blood spatter expert argues that it is all but impossible for the spatter to have been caused by a blow from a human. Samuel fell onto a shed, the second expert says, then bounced into the air, his body spinning, releasing blood in exactly the pattern discovered. It would have been nearly impossible for a human to have delivered the precise blow to make the spatter found. The second expert has test-dummy evidence and mock-up drawings to prove it. Sandra couldn’t have done it.

So what does the blood spatter really tell us? What does any evidence actually reveal about the world?

The point is that even hard physical evidence is often subject to interpretation and secondhand reevaluation, and that two utterly opposing views, even from credentialed subject matter experts, can seem just as convincing. Although the movie, to its credit, doesn’t wade into the broader cultural implications of this notion, it’s not too hard to see it as a comment on the raging debates about trust, truth, and information ecosystems in Western media and politics.

As the trial hurtles toward its end, the movie doesn’t just force viewers to weigh slippery, competing truths, it shows how difficult it can be to achieve certainty even when dealing with one’s own firsthand experiences. After all, what are memories but personal records, inaccessible to anyone else, and subject to reevaluation and reinterpretation like any other piece of evidence? Truth is illusory, experts say. But one thing we can be sure of is that Anatomy of a Fall is a very, very good movie.

The post In French Thriller <i>Anatomy of a Fall</i>, the Law Is No One's Friend appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>

This week’s featured article is “True Crime Distorts the Truth About Crime” by Kat Rosenfield.

This audio was generated using AI trained on the voice of Katherine Mangu-Ward.

Music Credits: “Deep in Thought” by CTRL S and “Sunsettling” by Man with Roses

The post <i>The Best of Reason</i>: True Crime Distorts the Truth About Crime appeared first on Reason.com.

]]>